|

||

|

Photos above: Josh Franzos

|

Look… to see, to remember, to enjoy

An early mantra of Carnegie Museum of Art’s Saturday art classes encouraged young art enthusiasts to take in the world with eyes and minds wide open. In honor of the program’s 80th anniversary, some grateful alumni look back.

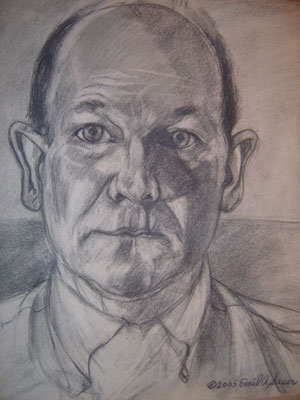

As a child in late-1950s Arizona, Emil Sauer chased jackrabbits on the ranchland that bordered his nascent Tempe neighborhood. So when Sauer arrived in Pittsburgh on what would become a fateful visit to an aunt and uncle in 1963, it was like entering another world. “When I came through the tunnels into Pittsburgh, it was like the Wizard of Oz,” says Sauer, now a professional artist living just outside Chicago. “I could see the blast furnaces burning, the glow from the mills, and the trains rolling through town. At night, orange ingots flew out of the trains, bouncing on the tracks like popsicles. There was nothing like it in the Southwest—it was bustling.”

His was the Pittsburgh of Gimbels, Horne’s, and Kaufmann’s; of Isaly’s ice cream, streetcars, and Kennywood. And perhaps most importantly, every Saturday for three years, it was the Pittsburgh of Tam O’Shanter art classes at Carnegie Museum of Art in Oakland. There, on a scholarship won through a poster contest, Sauer learned how to view, appreciate, and create artwork, like thousands of students before him and since. For its students, the Tam O’Shanter classes were as much a part of Pittsburgh lore as any of those better-known icons. For 80 years, the weekly sessions, under a variety of names—Tam O’Shanter, Palette, or The Art Connection, as the classes are called today—have been distinguished as much by stringent rules, sacrifice, and dedication as by famous teachers and students, not to mention a powerful sense of pride. Still going strong today, albeit with a much different format than the formal lectures of yesteryear, Carnegie Museum of Art’s Saturday art classes managed to continue long after the departure of legendary teachers such as Joseph Fitzpatrick and Ed Spar. They survived the Great Depression, a world war, and the rise and fall of art movements from Cubism to Pop. And Emil Sauer knows why. “You can’t teach creativity,” says Sauer, “that’s true. But in being creative around people, it provides a kind of instruction that goes beyond mere technique—it awakens that creativity in others. And that’s what these instructors did.”

Brush with Celebrity

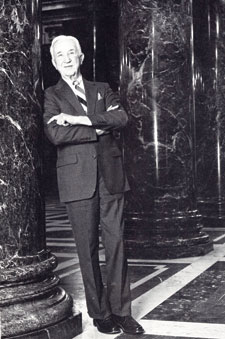

“We’d wait outside Carnegie Music Hall in separate lines—boys on one side, girls on the other,” recalls Braughler, now assistant curator of education at the Frick Art & Historical Center. “Mr. Fitzpatrick always walked to the museum, and you’d see him striding up Forbes Avenue towards the class, always impeccably dressed—elegant suits, a white shirt and tie, and snow-white hair. He’d slip in the back of the museum, and next time you saw him he’d be on stage. He was a celebrity.” As early as the 1940s, Fitzpatrick’s figure loomed over the Saturday art classes, which began in 1929 at the hands of Margaret Lee, the museum’s director of educational work. Through Fitzpatrick’s work as art supervisor for Pittsburgh Public Schools and the museum’s Tam O’Shanter and Palettes classes—which, if combined, gave children a continuous museum-based art-making experience from about 8 years old until their early teens—he educated thousands Yet, to see the photos of a crowded and impersonal Carnegie Music Hall, and to hear, at first blush, the descriptions of those weekly Saturday classes, it’s easy for a generation raised on modern educational concepts —classes more likely to have a student’s bill of rights than a dress code—to wonder: What was the appeal? Braughler was a student at Moore Elementary School in Brentwood when she was chosen by her art teacher to be one of two students from the third grade to represent the school as a Tam O’Shanter. Each school in the region contributed two third graders each year, which added up to hundreds of Tam O’Shanters when they all filed into the Music Hall in Oakland. Braughler recalls befriending the other Brentwood-area Tam O’Shanters on their carpool drives to Oakland—hers was the only mother who drove a car. She recalls the end-of-term trips to Isaly’s for ice cream, but also the relentless early Saturday mornings and the missed Friday-night pajama parties—a central social activity for girls of her era. Once inside the Music Hall, things were just as rigidly formed as the line outside. Each class saw a select handful of students, judged on the quality of their work, brought onstage to replicate their projects from the previous week—in front of everyone. The dress code, particularly for girls, was as strict as the one-piece-of-paper rule for distributed art materials. But there was something in those rules more important than the constrictions placed on a child’s young social life. There was a sense of honor, and the extension of respect. “They made it very clear, if you dropped out, they would never fill that spot,” impressing the honor of being a Tam O’Shanter on the children, says Braughler. “But there’s no question about it: Being able to go to that museum, participate in the class—it was a real treat. I can’t say why I never thought to say, ‘OK, I’ve had enough, I quit.’ But I didn’t. And it was a real hardship on my parents and the other parents.” It was rigorous instruction, recalls Emil Sauer. “But Fitzpatrick was so enthusiastic onstage—if I was drowsy, within a few minutes I’d be wide awake. He always had the attention of the whole room. That requires real mastery.”

The Taste of Artistic FreedomWhen Braughler and Sauer were students, Andy Warhol was just another graphic designer in New York City—himself a former Tam O’Shanter under Fitzpatrick’s tutelage—and Pop art, Abstract Expressionism, even Cubism were largely new concepts to everyday Pittsburghers. Saturday art classes lasted through changing artistic trends by remaining a malleable program rooted in a deep respect for the students and their learning experience. “We approach our students with an assumption, not of maturity, but of intelligence,” says Marilyn Russell, Carnegie Museum of Art’s chair and curator of education. “Sometimes in younger grades, art isn’t always thought of as having the rigor that a math class might have. But for people who appreciate art, it’s about what you see in the world, and what you believe to be noteworthy. And that’s serious.” In addition to her day job at the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council, Christiane Leach is a well-regarded and multi-talented artist, musician, and poet. And to her, a lot of

Ryan Freytag and Christiane Leach Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council & Saturday art class alumni 1980s and 1970s. Photo: Renee Rosensteel

As an African-American girl growing up in the less-than-affluent Pittsburgh neighborhood of Knoxville in the early 1970s, Leach notes that positive artistic influences were few and far between: There was her own household, with artist and musician parents, and, well, that was about it. But immediately upon being chosen for a scholarship to The Art Connection, Leach was sure Carnegie Museum of Art was where she belonged. “This was the 1970s, shortly after the civil rights movement, and my public school teachers were trying, but they were older, and it just wasn’t there,” says Leach. “The teachers at the Carnegie were of an attitude that was very open, very engaging—they were younger and artists, and they were the first ones who talked to me the same way as other students. Even when they’d comment on your work, it was so different from public school art teachers, it was really beautiful for me. It was my first step outside of the neighborhood, and my first taste of artistic freedom.” Freedom might not be the first word associated with the Fitzpatrick-era Tam O’Shanters. But today, “freedom”—at least within the class’s well-defined structure—is an idea that is jealously guarded by Carnegie Museum of Art’s Saturday art class instructors and students alike. “The Art Connection taught me to go outside the boundaries,” says Marian Day, a mid-1990s alumna who today is the sole art teacher for Cornell School District, which includes students from Coraopolis and Neville Island. “They were very supportive of that freedom. It was a big lesson to learn—that what I had pictured in my head at first wasn’t necessarily the final product. I learned that I enjoyed the journey more than the final piece itself.”

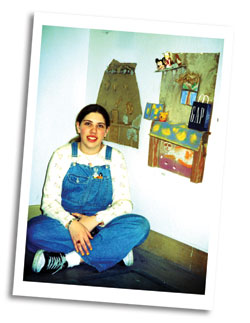

Marian Day, Art teacher, Cornell School District, and 1990s alumna. Photo: Renee Rosensteel

Right: Marian Day, more than a decade ago, with her Saturday art class masterpieces.

The Side EffectsIn today’s classes, young people from all over the Pittsburgh area reign over “their” museum—students whose parents enroll them, as well as those chosen for one of about 100 annual scholarships. On the first day of the most recent winter session, before heading for the classroom to allow students to try their hand at drawing landscapes, Pittsburgh artist Ashley Andrykovitch discussed with her fifth-grade class landscapes by diverse artists, from Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet to Pittsburgh’s famed folk painter John Kane. Any art class can discuss Van Gogh and Kane, but The Art Connection has the unique opportunity to do so while standing in front of the actual work. And despite their age—barely breaking double-digits—Andrykovitch’s students are never quiet when it comes to discussing the museum’s collection. “They’re not shy,” she laughs. “At each painting, I sit them down and have them share their observations. It’s a good exercise in getting them to elaborate—in changing something visual into something verbal. They learn to justify their responses, which is empowering to the students, because there’s no right or wrong answer.” The Museum of Art teaches its students not necessarily how to achieve the absolute pinnacle of drawing technique but how to see and understand nuances in whatever it is they see. One of the side effects of this method, albeit an important, purposeful one, is an understanding of art as a potential career path. Ryan Freytag spent the better part of his early life in The Art Connection—first as a student, then, while studying art at Carnegie Mellon University, as a teacher’s assistant to his former instructor, Ed Spar. Now 29, Freytag works next to Christiane Leach as the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council manager of cultural policy and research. It’s a career path he attributes directly to his time at the museum’s Saturday art classes. “One week every semester we’d do a ‘behind the scenes’ lesson looking at something like the creation of a museum exhibition,” says Freytag. “It inspired me to work in the arts. I went into art in college knowing I didn’t want to be an art teacher, but that I probably wasn’t going to be a professional artist, either. But I knew from my classes that there were all these other options; so many other doors to open.” Alumni of Tam O’Shanter, Palette, and The Art Connection classes are invited to join current students to celebrate 80 years of Saturday art classes during the program’s opening night of its annual student exhibition from 3:30 to 6 p.m., April 5, in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Hall of Sculpture. Please RSVP to TAC@carnegiemuseums.org or call 412.622.3293. The exhibition will remain on view to the public through April 19. |

|

Carnegie Museums After Dark · Art Without Walls · Recollecting Andrey Avinoff · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Kim Amey · About Town: Art in Bloom · Field Trip: Year of Restoration · Science & Nature: Scientists Among Us · Artistic License: Bosom Buddies · Another Look: 13 Most Beautiful… · Then & Now: Earth Day

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

Tragically, as he was preparing to go home, Sauer’s aunt and uncle got a call: His mother had died suddenly, and just like that, Pittsburgh became the young man’s new home.

Tragically, as he was preparing to go home, Sauer’s aunt and uncle got a call: His mother had died suddenly, and just like that, Pittsburgh became the young man’s new home.  Even as a young girl, only 8 years old when she became a Tam O’Shanter in the late 1950s, Beth Braughler recognized there was something special about Joseph Fitzpatrick. Something that, perhaps, none of her other teachers held. Sure, he was strict—Saturday mornings weren’t time for socializing. But Braughler and her classmates recognized that Fitzpatrick’s strictness came from a place of respect, not bossiness, and the students returned that respect pound for pound, with adoration.

Even as a young girl, only 8 years old when she became a Tam O’Shanter in the late 1950s, Beth Braughler recognized there was something special about Joseph Fitzpatrick. Something that, perhaps, none of her other teachers held. Sure, he was strict—Saturday mornings weren’t time for socializing. But Braughler and her classmates recognized that Fitzpatrick’s strictness came from a place of respect, not bossiness, and the students returned that respect pound for pound, with adoration.