|

||

Gigapan courtesy of Global Connection Project |

Art Without Walls Art Without WallsFor a group of teenage and 20-something Brazilians from vastly different worlds, it began as a simple invitation: work together to explore life in a local favela called Morro do Palácio, a massive shantytown built into a hillside just outside Rio de Janeiro. Home to many of the youths yet something altogether foreign to the university students among them, the favela— usually a point of division—would soon prove to be an important point of intersection. The invitation came at the request of two unlikely sources: The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, world-famous for being the home of everything to do with Andy Warhol, and the Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC) in Niterói, Brazil, probably best known for its spectacular building overlooking Guanabara Bay, a product of renowned Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer. While continents apart, the museums are equally determined to make a difference in their communities, and are known for thinking outside the box. “The goal of the partnership is to build on strengths,” says Tresa Varner, curator of education and interpretation at The Warhol, who worked briefly at the museum in Niterói during an educator exchange. “We want to take some of the best practices of The Warhol working in the community, like our RUST (Radical Urban Silkscreen Team) program, and share it with the Brazilians, and then take some of the programs that MAC has been doing in collaboration with local preventive health initiatives, and bring them here.” Named “Comuniarte” by the students, the collaboration—which includes a key partnership with the Federal University in Niterói and a sponsorship by Oi Futuro, a telecommunications foundation in Rio—has already reaped a number of fascinating outcomes, including the mapping of the favela. The projects have managed to not only positively change how the youths see themselves and where they live, but how educators empower their charges—not just in Brazil, but in Pittsburgh and beyond. Communicating Through ArtJessica Gogan, curator of special projects at The Warhol, together with Luiz Guilherme Vergara, former director of MAC and professor of art at the Federal University in Niterói, crafted the partnership. The concept for Comuniarte, Gogan says, is simple: Connect art, health, and social justice, give it a supportive framework, and watch what happens. “Part of our strategy was to engage a deeper sense of awareness by giving these young people tools they can use to discover their own sense of belonging, so that they can then become active in helping their communities,” says Gogan, who has been splitting her time between Pittsburgh and Brazil for the past two years. In keeping with the practice of extending far beyond their own walls, the museums kicked it up a notch by also bringing into the fold faculty and students from the university. Over the course of a year, museum educators, artists, and an interdisciplinary team of faculty in the fields of medicine, geography, literature, education, and art, introduced the students—six from the university (each from a different discipline) and a dozen from the favela—to the concept of mapping, both literal and metaphorical. The youth then worked together on projects that “mapped” various aspects of the favela community with the goal of consciousness-raising, valuing community life, building citizenship, and becoming forces of change. In one interpretation of a physical map of the community, a student labeled each section of the favela with a genre of music that corresponded with the area’s perceived level of danger. The section marked Samba, for example, was generally safe compared to that tagged Hip Hop and Rap. Dangers aside, there is little government support in any of these neighborhoods, often the water supply and sewer systems are makeshift, and homes are more often than not powered by siphoned electricity. Enveloped by poverty, drugs, and gang warfare, life is hard. Yet, there are still spaces of great affection, from alleyways where youth played as kids to one area that regularly brings people together, the football field. “Favelas are densely compact spaces, houses are built on top of each other; the football field is the only open and expansive space,” says Gogan. “So, one group of students explored the nature and history of the football field, focusing on it as a place of health.”

A Community AffairInspiring some of its country’s poorest youth has been a longtime passion for Brazil’s contemporary art museum. From one side of its building, the museum overlooks the ocean; on the opposite side, luxury flats rest not far above, and just above the flats, at the highest elevation, sits the sprawling favela Morro do Palácio. In 1998, the museum piloted an outreach program inspired by influential Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica, whose influential Environmental Program, inspired by Mangueira, a famous favela and Samba community in Rio, embraces ideas of artists working outside museums. For nearly a decade, MAC educators have partnered with local artists to deliver workshops that taught youth how to hand-make paper (which they then sold in the museum store). Participants also learned how to express themselves through dance, music, and graffiti. All the while, educators worked alongside a network of doctors, nurses, and social workers already imbedded in the community as part of the local Family Doctor Program, an initiative that originated in Cuba and focuses on preventative care. Evaluations by the health care workers noted that the youth not only responded positively to the activities led by the museum, but that their health improved, and they became more engaged in their communities. Over time, some of the youth became artists and educators, and others worked in maintenance at the museum. The senior citizens they involved in some of their community projects also benefited in some incredibly tangible ways: lower blood pressure and decreased episodes of depression. It was this intersection between medicine and art that first captivated Gogan, who two years ago was one of several educators from The Warhol and Carnegie Museum of Art who team-taught an art class to University of Pittsburgh medical students. The intent of the course was to help the doctors-in-training learn the fine art of becoming “Through our involvement with the medical school in Pittsburgh, particularly discussions with faculty, and the Family Doctor Program in Brazil, we began to see distinct similarities in the emerging practices and dialogues in the fields of human rights, education, health, and art,” Gogan says. In other words, educators need to think about the “learner” in context of all four fields.

Students interviewed members of their community, including one another. They also designed a logo for the program.

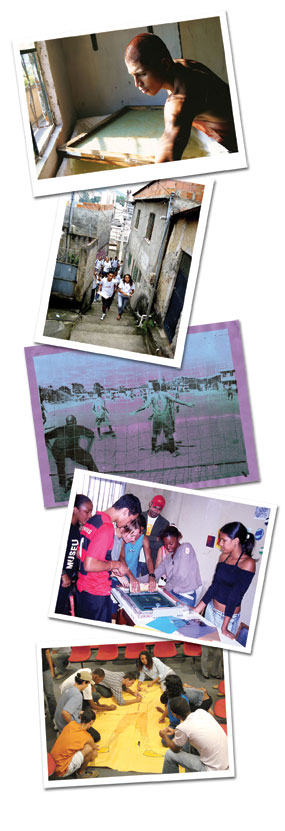

Mapping LifeAs a way to help the students explore and map the favela, Gogan, in tandem with MAC educators and the interdisciplinary team of Federal University faculty, introduced them to some of Andy Warhol’s artistic practices: silkscreening, collecting and documenting, and his famous series of short portrait films, Screen Tests. The students created their own “time capsules” reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s famed cardboard boxes filled with the artifacts of his daily life. They also took turns in front of and behind the camera, and filming museum visitors. One group decided to turn the camera to the football field. “They chose three different angles of the field and did three-minute films, basically riffing off of Warhol’s Screen Tests, but they took it and made it their own,” Gogan says. As part of a documenting exercise, students—always a mix of favela and university students, ages 16 to 26—fanned out into the community, interviewing neighbors, some of whom had lived in Morro do Palácio for 30 or 40 years. Their subjects told stories of unforgettable championships played on the field, and reminisced about neighborhood barbeques that spontaneously unfolded there. One group of students explored private spaces within the community. They took photographs, made sketches of homes, and conducted interviews. As their final project, they created specially designed objects—a small book or piece of art—for each of the residents they interviewed.

“For the university students, who before this experience had never set foot in a favela, it changed their perception of their field and forever changed their preconceptions of others.”

Students designed gifts for community members they interviewed.

A is for ActivismWhat young person doesn’t like the idea of putting their thoughts on a t-shirt—it’s fun and immediate. These qualities, coupled with an activist spirit, is the driving force behind RUST, The Warhol’s Radical Urban Silkscreen Team, a project of The Warhol and Artists Image Resource (AIR), an artist-run organization in Pittsburgh that specializes in fine art printmaking. Last summer, 10 Pittsburgh-area high-schoolers spent four hours a day, four days a week learning printmaking and design skills in order to create print materials for local grassroots groups with a social agenda. This easily-portable, low-cost and, most importantly, empowering program was a natural choice to reproduce in Brazil, so RUST went on the road this past fall by way of Warhol educator and artist Heather White and AIR’s Bill Rodgers. White and other RUST artists labored for months to work out the kinks of a new portable silkscreening cart in anticipation of the trip, trying it out at the farmers market and during a festival on the streets of the North Side. They knew that the favela provided plenty of challenges: no running water, unreliable electricity, and then there was the minor detail of a language barrier between teacher and student. “Bill and I don’t speak Portuguese, so it was challenging,” says White. “But we found ways to communicate—thumbs-up, smiles—and the students jumped right in and were really engaged. They had a ton of energy and ideas.” Students created silkscreens of alleyways, homes, and the football field. And the portable cart, scanner, laptop, printer, and light table—all battery-powered—that White and Rodgers left behind are still being put to good use in the favela’s brand-new community center, an annex of MAC also designed by Oscar Niemeyer, which opened in December. “As a young person, maybe you don’t think about your ability to affect change,” notes White. “But then you have the skills to help your local farmers market get the word out with promotional materials you create and you start to realize the power you have to participate in ways that are meaningful to you. You start to recognize that your history and your future are as important as anyone else’s.”

Meeting of the MindsIn May, the Comuniarte project will be featured in Pittsburgh as one of the case studies at Pitt’s Global Academic Partnership Conference titled, “The Arts, Human Development, and Human Rights: 21st Century Intersections and Ramifications.” Gogan, along with David Barnard, professor of medicine and director of palliative care education in Pitt's School of Medicine and Center for Bioethics and Health Law, and Pitt’s Director of Latin American Studies Kathleen DeWalt, wrote the conference grant. The reward: a workshop-style conference that will draw the brainpower of not only all those involved in the Pittsburgh-Niterói partnership, but Pitt faculty from the fields of medicine, law, bioethics, education, art, and art history. They’ll also include local groups like the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, each of which will swap stories about the impact of social justice programs here in Pittsburgh. One example, which also involves RUST, is a partnership between Pitt law students and area youth to create a Street Law curriculum with the goal of better educating today’s youths about their legal rights. “The model of a museum as something more than just the walls of a building and art being more than just physical objects in a museum is something I know The Warhol believes in,” says Barnard, who, before arriving at Pitt in 1999, was chair of the department of humanities at Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, the first medical school in the country to require its students to take courses in the humanities. “We’re hoping this idea can take on even more life in Pittsburgh, partly stimulated by what we learn from the Brazilians, but also through an even broader world context for art and human rights work that’s happening all over the world.” It’s certainly made its mark in Niterói. “In the beginning, the students weren't that concerned about each other,” says Brenner. “The students from the favela, some had a really hard time with physical contact. But over time they began to show affection and this played out in their family life, too. Mothers noticed the difference.” It’s an achievement not lost on the students themselves. “Right from the beginning we worked in groups,” Jocimar Lyrio wrote in an evaluation of the program, translated into English. “I discovered great opportunities for my life, to create an open and warm environment, to help us be with our families and to work together with people.” Added peer Camila Thompson: “I feel the possibilities, and that they could disappear, so

|

|

Carnegie Museums After Dark · Recollecting Andrey Avinoff · Look… to see, to remember, to enjoy · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Kim Amey · About Town: Art in Bloom · Field Trip: Year of Restoration · Science & Nature: Scientists Among Us · Artistic License: Bosom Buddies · Another Look: 13 Most Beautiful… · Then & Now: Earth Day

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

“When we started the project, one of the young men from the favela had not one positive thing to say about his community,” says Ana Karina Brenner, a Brazilian psychologist and educator who was the project’s pedagogic coordinator. “He could only see the bad things and how he needed to find a way out. By the end, he said there was a place for him; that he wanted to take part, to help.

“When we started the project, one of the young men from the favela had not one positive thing to say about his community,” says Ana Karina Brenner, a Brazilian psychologist and educator who was the project’s pedagogic coordinator. “He could only see the bad things and how he needed to find a way out. By the end, he said there was a place for him; that he wanted to take part, to help.