Fall 2008

|

||

Tracy Myers, co-curator of Worlds Away: New Suburban Landscapes exploring the bustling northern suburb of Cranberry Township.

“ A lot of people define suburbia in the same way one Supreme Court justice defined ‘obscenity’ in 1964:

‘I know it when I see it.’” -Tracy Myers, co-curator of Worlds Away |

Burb Appeal

In an upcoming exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art, artists and architects explore the once unmentionable canvas of the suburbs, only to expose a landscape surprisingly in flux—and one that, in many ways, is as complex and intriguing as any city. For Tracy Myers, co-curator of the first major museum exhibition to explore suburbia through the lens of art and architecture, two photographs uniquely tell the story. The first, by one-time forensic photographer Angela Strassheim, shows a family saying grace inside the home of the Big Mac. At the far end of the table, at the center of the image, the teenage daughter looks away, wearing an expression somewhere between boredom and distraction.The other image, part of Larry Sultan’s series The Valley, shows another disinterested young woman. This time it’s an adult film actress on a shoot in a backyard in California’s San Fernando Valley. The setting is mundane: The woman talks on a cordless phone near a backyard pool, with a trio of dogs sniffing their surroundings. The woman’s robe, pumps, and short shorts are racy, but the scene has a pedestrian air. It is porn as workplace. These two visions, of fast-food virtue and middle-brow vice, neatly illustrate the central theme of the exhibition Worlds Away: New Suburban Landscapes—that there’s way more going on in the suburbs than a lot of folks think.  Laura E. Migliorino, Egret Street, 2006, ink-jet on canvas. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Justin Smith Purchase Fund, 2007

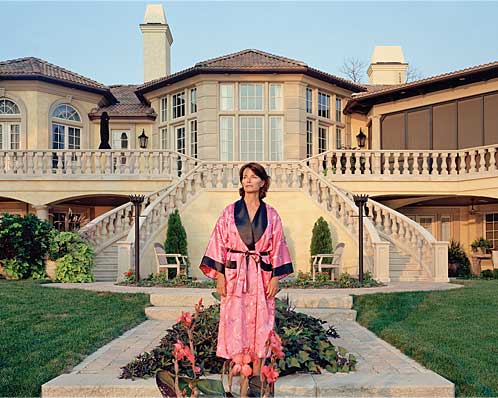

“These two photos represent the alpha and omega of human behaviors,” says Myers, curator of the Heinz Architectural Center at Carnegie Museum of Art, which will host the show beginning October 4. “To me, they sort of bracket a wide spectrum of practices. We wouldn’t expect to find both extremes in suburbia, but they seem to coexist there.” Through architectural installations and drawings, paintings, photography, sculpture, textiles, and film, Worlds Away highlights these extremes, and lots of places in between. Myers and co-curator Andrew Blauvelt, design director and curator at the edgy Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, wanted to shine a spotlight on a part of the country most artists have traditionally overlooked.  LTL Architects, New Suburbanism, 2000, sectioned perspective (street), digital lamda chromogenic color print on photographic paper. Carnegie Museum of Art, gift of the Drue Heinz Trust“Most architecture critics and curators are kind of urban snobs and look down on suburbia,” says Myers. “Our curatorial point of view for this exhibition is that more than 50 percent of the population of the United States now lives in the suburbs, and there’s a reason people want to live there. The suburbs aren’t going away. So our job is to look at how artists and architects are reflecting on the suburbs and, where possible, suggest new ways of thinking about suburbia’s physical form.” Home of the McMansionThere are many critiques of suburbia, ranging from the aesthetic—it has been referred to as “the geography of nowhere”—to the ecological, all having to do with problems created by a lifestyle of McMansions, Garage-Mahals, and drive-thru Café Lattes. But most critics of suburbia don’t live there, Blauvelt points out. “A lot of post–World War II criticism of suburbia was by city dwellers imagining what life in the suburbs was like,” he says. Angela Strassheim, Untitled (Elsa), 2004, chromogenic print. Courtesy the artist and Marvelli Gallery, New YorkThese critiques have contributed to a simplistic mythology of suburbia—it’s seen as a middle-class utopia on one hand and a stifling backwater of conformity on the other. Worlds Away takes a more nuanced view of its subject. The show is divided into three sections, translating roughly to the iron tripod of suburban life: house, mall, and car. Each part of the exhibition shows work by artists and architects engaging current conditions in these environments. The result is a show that displays a suburbia in flux, a place as full of contradiction as any city. Discarded tract homes from San Diego, recycled as housing on the crowded arroyos of nearby Tijuana, Mexico, are the subjects of one architect’s take on modern-day suburbia. Aerial photographs of Los Angeles parking lots reveal the sparse beauty in their geometric forms. The floor plan of a house, created by hoeing a 20-acre barley field adjacent to a typical subdivision, speaks to encroachment on rural areas as suburbs expand ever farther into the landscape. For Myers, her path to Worlds Away began when the museum acquired a series of prospective renderings by LTL Architects that reinterpret the “big-box” (think strip mall chain store) landscape. In these drawings, LTL envisioned houses built on top of a big–box store. The dwellings share the resources of their commercial neighbors below—heating, cooling, and parking— while maintaining a separate residential space. “It got me thinking about suburbia as a development pattern and a social phenomenon, and I wondered whether we could put together a whole show on how artists and architects were reflecting on the topic,” says Myers, herself a product of a suburban childhood. It so happened that Blauvelt was working on a similar project. Collaborating with the Walker, Myers says, “was a no-brainer.” The curators pooled resources and expertise—Myers in architecture, Blauvelt in visual arts—as well as the institutional weight of Carnegie Museum of Art and the Walker to produce a show that will travel to Yale University after its stop this fall in Pittsburgh. Worlds Away debuted at the Walker this past February to wide acclaim. It’s a Burgh Thing, TooThe images and architectural renderings of Worlds Away should resonate in Pittsburgh, which has seen its suburbs swell in recent years. Though the population of the city’s metropolitan area has shrunk by 8 percent since 1980, the amount of developed land has increased by 43 percent.The suburbs around Pittsburgh have also become more diverse. Scott Township, just south of Pittsburgh, has more foreign-born residents per capita—about 9 percent, many of them Indian Americans—than any other community in southwestern Pennsylvania. Hindu temples and Indian restaurants dot the eastern and southern suburbs. There are significant African-American populations in Monroeville, Penn Hills, and Sewickley. The same is true across the nation. Ethnic minorities (27 percent) and childless households (29 percent) now make up substantial portions of the suburban population around the country, according to Blauvelt. These realities might blow up stereotypes of suburbia as the exclusive domain of white, heterosexual couples with children. “Suburbia is much more diverse and far less monolithic than we might think,” Myers says. “The cities aren’t necessarily the first place immigrants come to anymore. In a lot of cases, they’re going directly to the suburbs.” In Worlds Away, the new demographics of the suburbs are illustrated in a number of works. Laura E. Migliorino’s multiple-exposed photos of suburbanites in front of their homes show, among others, an African-American family and a Hindi-American woman clothed in a sari. Re-inhabited Circle Ks, Paho Mann’s series of photographs documenting new uses for the chain convenience stores, includes a store in Phoenix, Arizona, that has been converted into a Mexican food restaurant; another is a Dollar Store with signs in Spanish. This is not the “Leave it to Beaver” suburb seared into the popular imagination. “The show underscores how suburbia has really changed,” notes Blauvelt. “But to a lot of people, their view of the suburbs is frozen in the 1950s.” Art’s Last FrontierMyers and Blauvelt both agreed: Neither wanted to define what constitutes a suburb. “In a lot of analysis of land use, the terms ‘metropolitan’, ‘urban’, and ‘suburban’ are used in the same sentence, almost interchangeably,” Myers says. “A lot of people define suburbia in the same way one Supreme Court justice defined ‘obscenity’ in 1964: ‘I know it when I see it.’”Making this definition even more slippery is the fact that the traditional elements separating city from suburb have largely melted away. “Urban” problems like crime and abandonment—especially with the mortgage crisis—have crept into many suburbs. And cities have begun emulating suburbs—witness urban developments brimming with chain stores and “anchor” tenant layouts.  Chris Ballantyne, Untitled (Additions), 2004, acrylic on birch panel. Collection Anthony Terrana, Wellesley, Massachusetts. Courtesy Peres Projects, Los AngelesAs suburbs have become more ubiquitous, Worlds Away shows how some architects are casting off their discipline’s historical aversion to the topic. In addition to LTL’s big-box project, the show includes the imaginative designs of Sculpture in the Environment (SITE). In its designs for Best Products, a now-defunct chain of catalogue showroom stores, SITE explored the big box as an artistic medium. One store (unbuilt) is enveloped in undulating waves of an asphalt parking lot; in another, the façade is peeling off; the corner of yet another pulls away from the rest of the building to reveal its entrance. But SITE and LTL are the exception, Myers says. Most architects steer clear of the suburbs. One reason: Suburbanites haven’t demanded much in the way of design. That may be starting to change, though, as some suburban planners are starting to ponder ways to curb traffic, improve accessibility, and generally make their communities look better. Carnegie Museum of Art was involved in one such local effort. In 2007, the museum partnered with the Airport Corridor Transportation Association (ACTA) on a design workshop for the Robinson Township/North Fayette area west of Pittsburgh. “It’s a big blob of stores and offices,” says Lynn Manion, executive director of ACTA, which is tasked with increasing mobility in the area. “This is a downtown for people in the western suburbs, but there’s no center to it. It’s not very people-scaled.” ACTA and the Museum of Art brought a group of local students and educators together with design and planning professionals to look at suburban mobility, design, and livability issues. The group learned about concepts like “desire lines”—those footpaths carved by pedestrians into road shoulders and hillsides where sidewalks don’t, but probably should, exist. T.J. Ray, a Moon Area High School senior who took part in the workshop, said a watershed moment for him came when the group took “a short, treacherous” walk around Robinson Towne Center, a super-strip of some 50 shops and restaurants. “Just trying to cross a street was a nightmare,” he says. The group all agreed on one thing: The area needs sidewalks. The students also dreamed up bus depots, parks, and a library inside a shopping center. ACTA is already studying improved bus and pedestrian access in the area. Earlier this year, the Museum of Art received the Supporting ACTA Initiatives Award for its part in the design workshop, and the excercise has generated interest from across the country and nearby municipalities. The trend toward sustainability is seen in Cranberry Township, a “boomburb” north of Pittsburgh that has watched its population more than double since the early 1990s. From a current population of 28,000, the community could have as many as 60,000 residents in 25 years, says John Trant Jr., Cranberry’s chief strategic planning officer. The township has passed aggressive land use laws, and the municipality is seeing more applications for developments that incorporate what Trant calls “an old-town community feel.” Some have grid-like road networks, small lots, and sidewalks. Others allow for a mix of residential and commercial uses. In other words, they look an awful lot like the towns and cities people used to live in. Trant says Cranberry’s supervisors have learned what might be termed the lesson of the strip mall. “A strip mall that’s designed as a strip mall today can only be a strip mall, nothing more. In 10 or 20 years, which is the life cycle of most strip malls, it will be a blight,” Trant says. Myers would like the exhibition to inspire more critical thinking—by city planners, architects, artists, and residents—about the places we call home. “My hope is that people who see the show will be more aware of the world around them, wherever they live.” |

|

Also in this issue:

Dream Machine · Transformers · Speaking Their Language · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Andy Mack · Artistic License: In the Name of Hybrid Theater · Science & Nature: The Herp House · About Town: A Road Map to Scientific Treasure · Another Look: The Child Mummy

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |