|

|

The Child Mummy

- By Betsy Momich

Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt isn’t the largest exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, but it is one of the most popular. That’s because, second only to dinosaurs, everyone loves a mummy. And Walton Hall has eight of them: the bound remains of an adult male who lived sometime between 1 and 200 A.D., a child who lived about 300 B.C., two cats, an ibis bird, a Nile Perch, and two juvenile crocodiles. Seems the Egyptians loved their animals, too, and honored them through mummification. Some of those animals were even considered sacred since the Egyptians believed they closely resembled certain gods. “Sobek” was a popular Egyptian god with a crocodile-like head, and “Bast” was a cat-headed goddess who, not surprisingly, held cats in high regard. Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt isn’t the largest exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, but it is one of the most popular. That’s because, second only to dinosaurs, everyone loves a mummy. And Walton Hall has eight of them: the bound remains of an adult male who lived sometime between 1 and 200 A.D., a child who lived about 300 B.C., two cats, an ibis bird, a Nile Perch, and two juvenile crocodiles. Seems the Egyptians loved their animals, too, and honored them through mummification. Some of those animals were even considered sacred since the Egyptians believed they closely resembled certain gods. “Sobek” was a popular Egyptian god with a crocodile-like head, and “Bast” was a cat-headed goddess who, not surprisingly, held cats in high regard.

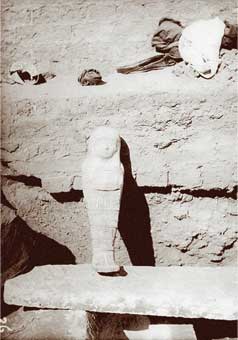

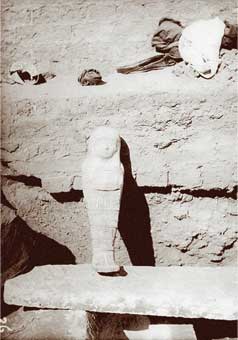

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s child mummy

at the site of his discovery in 1911

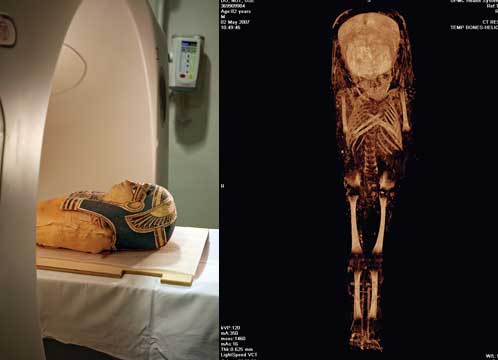

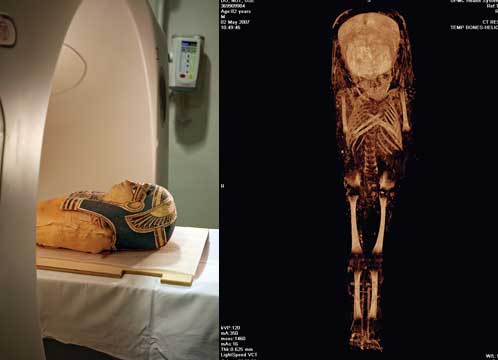

On May 2, 2007, by far the most popular of the Carnegie Museums mummies was the 2-foot-4-inch mummy of what we now know was a young boy from Abydos, Egypt. At about 10:30 that morning, TV camera crews and print reporters joined Museum of Natural History Anthropology Curator Sandra Olsen as she eagerly observed something that doesn’t happen just any day: the “digital dissection” of a mummy by way of CT scanning. In this case, the 1,700 CT scans of the tiny coffin and its precious cargo were performed by Jeffrey Towers, chief of musculoskeletal radiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Prior to the scanning, Olsen had estimated the child to be about 8 or 9 years old and suspected that he/she might have suffered from a genetic ailment because of an unusually large head. What she learned after the scans were completed was that the child was, in fact, male; he was about 3 years old, which Olsen and her Pitt Medical School collaborators determined through three-dimensional dental scans; and, since the head of a 3-year-old is typically disproportionately larger than his/her still-growing body, the head size of this young Egyptian was, in fact, just right.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s child mummy at UPMC for his CT scan in 2007

Olsen learned that other things weren’t okay, however. At not even 3 feet tall, this toddler was small even by Egyptian standards. And through 3-D scans of the boy’s cranium, the investigating team discovered a delayed closure of the anterior fontanel (or “soft spot”) and learned that the skull itself was smaller than average. The team’s diagnosis: his small size, smaller-than-average cranium, and still-prevalent soft spot could be signs of a condition called hypothyroidism, or severe thyroid deficiency, an ailment that Olsen explains “is still endemic in Egypt today.”

The team also learned a thing or two more about the mortuary practices of the day—specifically those applied to elite but non-royal children.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History purchased the 2,000-year-old rare mummy from Swiss Egyptologist Henri Edouard Naville in 1912, about a year after British Egyptologist T. Eric Peet joined Naville’s expedition and unearthed the mummy in the only intact tomb left in an Abydos cemetery. The tomb’s contents included seven adult mummies in limestone sarcophagi (stone coffins) and five child mummies in wooden coffins. Inside each coffin, each mummy was elaborately decorated with a mask, a breastplate, three panels over the legs, and a foot covering.

Olsen says the coffin of the child mummy had been x-rayed in the 1940s and again in 1986, “but the information gathered from x-ray technology was limited,” she notes. “We had so many more questions. That’s what archaeology is all about: answering questions.”

Now they have some of those answers. “From an archaeologist’s point of view, we now know this little fellow inside and out,” Olsen says. She explains that researchers are manipulating the 1,700 images taken during the scan to develop a skin rendering and a three-dimensional computer image of the boy’s head for both exhibit and study. “What I dream of one day is having a complete reconstruction of him on exhibit playing the Egyptian game Senet,” she says.

At the very least, Olsen plans to display some of the CT scans beside the child mummy, which immediately went back on display in Walton Hall after its momentous, one-day visit to UPMC. |

|

Fall 2008

Fall 2008 Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt isn’t the largest exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, but it is one of the most popular. That’s because, second only to dinosaurs, everyone loves a mummy. And Walton Hall has eight of them: the bound remains of an adult male who lived sometime between 1 and 200 A.D., a child who lived about 300 B.C., two cats, an ibis bird, a Nile Perch, and two juvenile crocodiles. Seems the Egyptians loved their animals, too, and honored them through mummification. Some of those animals were even considered sacred since the Egyptians believed they closely resembled certain gods. “Sobek” was a popular Egyptian god with a crocodile-like head, and “Bast” was a cat-headed goddess who, not surprisingly, held cats in high regard.

Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt isn’t the largest exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, but it is one of the most popular. That’s because, second only to dinosaurs, everyone loves a mummy. And Walton Hall has eight of them: the bound remains of an adult male who lived sometime between 1 and 200 A.D., a child who lived about 300 B.C., two cats, an ibis bird, a Nile Perch, and two juvenile crocodiles. Seems the Egyptians loved their animals, too, and honored them through mummification. Some of those animals were even considered sacred since the Egyptians believed they closely resembled certain gods. “Sobek” was a popular Egyptian god with a crocodile-like head, and “Bast” was a cat-headed goddess who, not surprisingly, held cats in high regard.