|

||

“It was the most colossal undertaking of its kind in the history of the world.”

- William Holland

|

From Trophies to Treasures

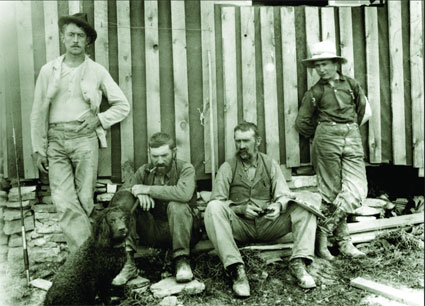

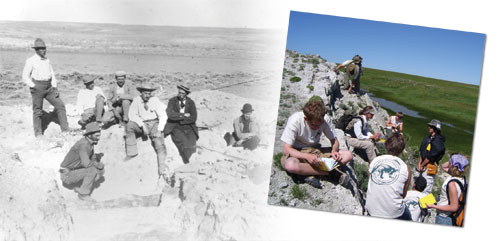

One stood barely five feet tall, hailed from Scotland, and was 63 years old. The other was a Wyoming native, stood 12 feet tall at the hips, stretched more than 84 feet, and was a bit long in the tooth at 150 million years old. One rose to the very top of the dog-eat-dog world of capitalism. The other roamed the land gobbling up huge amounts of vegetation. An odd couple, yes. But the two were made for each other, and their relationship captivated the world. Such was the saga of Andrew Carnegie and Diplodocus carnegii, and the cast of characters—before and after them—who became swept up in the late 19th-century trophy hunt that quickly turned into one of the world’s most fascinating scientific journeys. As Andrew Carnegie was amassing his millions by doing his part to fuel the industrial revolution, gunfighters were still going at it in the 1800’s Wild West. And they weren’t the only ones. He credits Cope and Marsh with really starting it all. They were “intensely competitive men who intensely disliked one another,” says Rea. “It wasn’t only about science to them. It was about who could bring back the best trophy dinosaur.” And it was their bones wars that sparked the public’s imagination and fueled the demand for more dinosaur finds. A demand that an ambitious, impatient Pittsburgh industrialist couldn’t wait to fill. The Most Colossal Animal on Earth” Back in Pittsburgh, Andrew Carnegie had just about written the book on supply and demand. By 1895, however, having done just about everything an entrepreneur could do, Carnegie was working to add “philanthropist” to his list of accomplishments. His Pittsburgh museum and library complex were among his earliest forays into two decades of giving back. Unfortunately, just about the only scientific artifact his museum had to show at that point was a giant “Irish elk” Carnegie had bought from the British Museum. He needed something bigger. A whole lot bigger. Carnegie had originally hoped his friend Marsh would provide him with just what he was looking for. But Marsh died in 1898. A year later, while relaxing in his New York City apartment, Carnegie spied an article in the New York Journal about a University of Wyoming fossil collector named Bill Reed who had stumbled across the ancient remains of “The Most Colossal Animal on Earth.” That news report would prove to be exaggerated: The team led by Reed had found only one big bone. But Carnegie's interest was piqued. Oh Give Me a Home Where the Brontosaurus Roam Brontosaurus giganteus, as the dinosaur had been informally named, was just the thing Carnegie’s museum needed. He tore out the article and sent it to William Holland, his museum director, with orders to buy the dinosaur and bring it back.  Bonediggers camp: Paul Miller, Jacob L. Wortman, William Reed, and Willie Reed, Jr.Money was no object. But excavating, transporting, and mounting a specimen for Pittsburgh would be. According to Holland, it was “the most colossal undertaking of its kind in the history of the world.” And he would pull out all the stops to achieve his mission. Holland dashed off to Laramie, Wyoming, and hired Bill Reed away from his employer, the University of Wyoming. Then he headed to New York, where he lured Jacob Wortman from the American Museum to be Carnegie Museum’s first curator of vertebrate paleontology. Wortman would bring legendary fossil preparator Arthur Coggeshall with him. But once the three arrived at the site of Reed’s much-publicized dinosaur dig, there were no more bones to be found. So they moved their operation 20 miles away to Sheep Creek, where, in July 1899, they found two skeletons of gigantic, long-necked sauropod dinosaurs. Holland, not the easiest guy to work for, fired Wortman soon after they returned to Pittsburgh. He replaced him with John Bell Hatcher, noted paleontologist and fossil hunter who had invented the excavation grid system still used by paleontologists today. In 1901, Hatcher wisely dubbed Carnegie’s dinosaur Diplodocus carnegii, in honor of the man financing the project. But he never got to see the giant skeleton on display. A visionary and incurable workaholic, Hatcher died in 1905 of typhoid fever contracted by drinking tainted water—not on a remote dinosaur dig, but in Pittsburgh. Striking Jurassic Gold Diplodocus carnegii—the giant, plant-eating dinosaur the length of a tennis court, known affectionately as “Dippy” since the 1970s—was finally put on display in 1907, the featured attraction and only inhabitant of the Carnegie Museum’s newly added, $5 million Dinosaur Hall. But with all that space and just one lonely, albeit really big, dinosaur, the call went out for more fossils. In the spring of 1909, Holland hired paleontologist Earl Douglass and sent him to northeastern Utah. There, near the town of Jensen, Douglass found eight tail vertebrae of an Apatosaurus (formerly called Brontosaurus), arranged just as they were when the dinosaur was still kicking. Douglass and his team started digging, and they didn’t stop until they’d uncovered the most complete Apatosaurus skeleton ever found.  Sheep Creek expedition, 1899. Reed and Holland at work in Quarry D.Through 1922, those outcrops of the Morrison Formation, dubbed Dinosaur National Monument in 1915 after a proclamation by President Woodrow Wilson, would yield the greatest stockpile of Jurassic dinosaur bones ever found, including nearly all of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Jurassic collection. Still today, that collection ranks as the best of its kind in the world. There would prove to be enough bones to keep crews busy year-round for 13 years, as they removed more than 350 tons of fossils and rock. It wasn’t easy. The Carnegie team removed layers of sandstone with picks and shovels, sometimes even dynamite, to get to the bones. Those bones were then covered with paper and a protective jacket of plaster-soaked burlap strips. The jackets were labeled, placed in strong wooden crates, and hauled back to Pittsburgh in railroad boxcars—so many boxcars that Carnegie Museum of Natural History installed rail tracks in its basement (which remain today). “They’d work all summer in that quarry,” says Rea. “They’d crate the bones, and in the fall and winter they’d ship them by cart or truck to the railroad on roads that were horrible. Transport was difficult…and there was always a problem getting paid.” Of the roughly 20 nearly complete skeletons discovered by Douglass’ crew, six were erected in Dinosaur Hall through the early 1940s—three as standing dinosaurs, the others still encased in rock and plaster: Dryosaurus, Allosaurus, Camarasaurus (the most complete sauropod skeleton ever found), Stegosaurus, Camptosaurus, and Apatosaurus louisae. The Headless Apatosaurus When fossil hunters working for Othniel Marsh found the first Apatosaurus out West in the 1870s, it was missing a skull. Two decades later, in 1897, a team from the American Museum of Natural History in New York found another Apatosaurus skeleton in Wyoming, but it, too, was headless. When the American Museum got around to mounting its skeleton in 1905, they restored the missing skull with the blunt, boxy, broad-toothed cranium of another sauropod called Camarasaurus, which at the time was thought to be a close relative of Apatosaurus. It would stay there until the late 1970s. But the truth would be discovered decades earlier. It was about a decade after the American Museum find that Earl Douglass and his Carnegie team found Apatosaurus louisae—a specimen so complete it would become the “holotype” (or name-bearing specimen) for its species. It also was missing a skull. But fortunately, Douglass located a skull lying less than 15 feet from the neck of his Apatosaurus that he felt certain was a match. Problem was, it was obviously different than the American Museum’s supposed Apatosaurus skull. In 1915, as the giant Apatosaurus louisae was being erected in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaur Hall, Holland found himself torn between respect for Douglass and a reluctance to offend colleagues in New York. He decided to do nothing. So the Carnegie Apatosaurus stood headless until Holland’s death in 1932, after which his successor followed prevailing scientific opinion and plopped a Camarasaurus skull on top. The wrong head stayed on Apatosaurus louisae until the late 1970s, when a leading expert on sauropods, Jack McIntosh, reexamined the lore and legend of the dinosaur’s headless history. In 1978, McIntosh and Carnegie Museum paleontologist Dave Berman determined that Earl Douglass’ original discovery was the right one. The duo then published a definitive scientific paper on their findings, and in 1979, in a ceremony held in Dinosaur Hall, Carnegie Museum of Natural History finally set things right: They gave Apatosaurus louisae a cast of its proper head. All other museums with Apatosaurus displays soon followed suit. Since then, new discoveries of Apatosaurus skeletons with their skulls attached have proven Berman and McIntosh correct. Dinosaurs Make a Comeback The Carnegie team’s Jurassic finds slowed and then came to a halt in the 1920s—not so much because of a shortage of fossils but a lack of money. The man behind them, Earl Douglass, would die a poor man in 1931. Then came the Great Depression, the Second World War, the postwar boom, and decades of indifference about things like dinosaur bones. Tom Rea credits popular culture with spurring a revival in interest. With the movie Jurassic Park and other works, he notes, “people started talking about hot-blooded, fast-moving dinosaurs. People were interested again.” Rea likes to trace the evolution of dinosaur exploration from the trophy hunting of Marsh and Cope, to Carnegie’s blend of ego and philanthropy, to Douglass’ quest for scientific discovery. All have a place in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time. Their common link, he says, is William Holland. “Even though he was not a paleontologist by training, the people he hired brought a gradually more professional approach, which spread to all other museums as well,” Rea notes. “Those men took us from using dinosaur fossils to simply build shrines to the past, to a scientific age where we wanted to understand what the past was actually like…what life was like 150 million years ago.” And that quest to understand continues to this day. “What’s so wonderful about this period at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, as it opens its new dinosaur exhibit, is that the museum now has a full-time dinosaur paleontologist,” says Rea, referring to Matt Lamanna, assistant curator of paleontology and a genuine dinosaur hunter. “They recognize what an enormous strength they have in these dinosaurs. It’s a very exciting time.” FULL CIRCLE

The Golden Age of dinosaur paleontology in North America may have lasted from 1880 to 1920, but that doesn’t mean all the gold is gone.

|

|

Walking with the Dinosaurs · Tales from the Supporting Cast · The Popular Salon of the People: Then and Now · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Diplodocus carnegii · About Town: International Appeal · First Person: It takes a village to raise a dinosaur · Artistic License: Size Matters · Science & Nature: Bodies of Knowledge · Another Look: Neapolitan Presepio Celebrates

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

Not far from the site where Carnegie’s team dug up Diplodocus carnegii (aka, “Dippy”) in 1899, a Wyoming rancher’s land is bringing Carnegie Museum of Natural History full circle.

Not far from the site where Carnegie’s team dug up Diplodocus carnegii (aka, “Dippy”) in 1899, a Wyoming rancher’s land is bringing Carnegie Museum of Natural History full circle.