Winter 2007

Winter 2007|

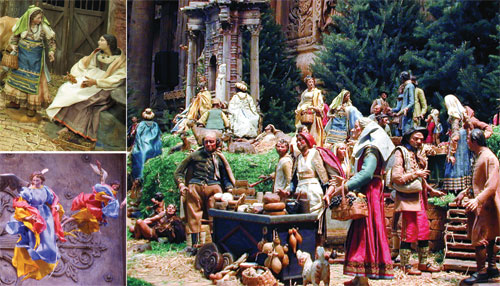

A stag stands proudly, his broad chest raised high. Below, village life carries on: a dog begs for sausages hanging from a meat stand, a fisherman casts out his net hoping for a good haul, and a band of Turks marches through the streets playing music while a mendicant lies nearby half clothed and exhausted. At the heart of this classic Neapolitan scene, a family rests with their newborn son. Angels soar overhead, and a shepherd dozes on a knoll below them. Each year for the past 50, on the day after Thanksgiving, this bustling scene has reemerged at Carnegie Museum of Art. An exhibition turned holiday tradition for many Pittsburghers, it’s more than an elaborate nativity scene; it’s one of the most complete Neapolitan presepi in the world, filled with 88 handcrafted human and angelic figures, 25 animals, and more than 100 architectural elements and props—such as the tempting sausages, watermelon, and cheese known as finimenti, or finishing touches, crafted of colorful pieces of wax. “This is the best of the best,” says Erich Cirilano, a presepio collector and historian, about Carnegie Museum of Art’s work. Cirilano’s family hails from Basilicata outside Naples. Twenty years ago, he purchased his first presepio figure and has been collecting, researching, and lecturing ever since. While at the height of their popularity in the 18th century, presepi included scenes based on Christian gospels but also had much more to do with depicting contemporary life in Naples. Beginning in the 17th century and lasting through the mid-19th century, wealthy Neapolitan residents commissioned presepi with figures characteristic of their homeland, including the stag, Roman ruins, the fisherman, and the band of travelers from the Middle East. Many characters are represented because they were part of everyday life, while others added something a little more meaningful. Take the stag, for example. The beast represents Christ, which is why it always makes an appearance, explains Cirilano. At international auctions, animals are particularly sought after because of their rarity, he adds. And while shepherds appear in traditional nativities, the sleeping shepherd in the presepio represents the world’s ignorance of the birth of Christ. Cirilano notes that shepherds were considered bawdy and crude and represent humans’ sinful nature. Other pieces remain important because they are associated with recognized names. Famed artists sculpted some of the meekest characters. The fisherman and the mendicant in the museum’s presepio represent what scholars call academic studies. Well known sculptors Lorenzo Vaccaro and Guiseppe Sammartino demonstrated their skills by fashioning these characters composed entirely of terracotta. Not only is the extraordinary detail employed by the artists worth a second look—the wheels of cheese, for example, bare the stamps of their makers—but it’s always a fresh experience visiting the exhibition because the museum follows the tradition of changing the scene on an annual basis. Rachel Delphia, assistant curator of decorative arts, says she likes to place the tearful woman carrying grapes beside another woman as if the two were talking about a problem, creating a dynamic moment. And special to this year’s exhibition: the 10 angels appear in traditional costumes made by artisans in Naples, thanks to a generous donation by Cirilano. Years of handling and exposure to light left the angels' original costumes in poor condition, and the museum first re-clothed them in 1994. Delphia says the next step is conserving the remaining original 18th- and 19th-century costumes. Also new to this year’s display: a green velvet skirt surrounding the display, thanks to donations by Florence Wyckoff Durfee and the Women's Committee of the Museum of Art.

The Neapolitan presepio is on view in the Hall of Architecture through January 6, 2008. Free docent-led tours are available Tuesdays through Sundays from noon-12:30 p.m. Meet in front of the Museum of Art store. |

Walking with the Dinosaurs · Tales from the Supporting Cast · From Trophies to Treasures · The Popular Salon of the People: Then and Now · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Diplodocus carnegii · About Town: International Appeal · First Person: It takes a village to raise a dinosaur · Artistic License: Size Matters · Science & Nature: Bodies of Knowledge

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |