Back

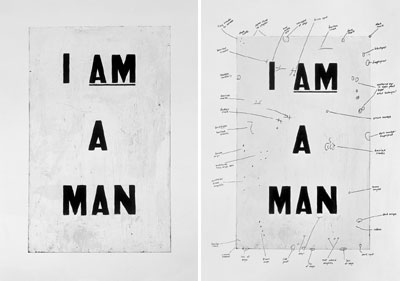

Condition Report, 2000, Silkscreen on iris prints, Courtesy

of the artist and Regen

Projects, Los Angeles.

In black text etched onto a black background run the vaguely

legible words: “I am an invisible man …” An

early-’70s photo of singer Stevie Wonder, with trademark

smile and ever-present sunglasses, is reproduced onto a

stenciled print and titled, “Self-Portrait At 11

Years Old.” In the cold font of 18th-century typeset,

crowned by a drawing of a chained African, an advertisement

describes a runaway slave—a slave named Glenn. In

the work of New York City-born and

-based artist Glenn Ligon, the pronoun “I” plays

a more pronounced role than in the work of many contemporary

artists. In each of these examples of Ligon’s heavily

textual paintings, etchings, and, more recently, multi-media

artworks, Ligon has managed to contort ideas of high art

and literature, popular culture, racial and sexual identity,

and self-portraiture itself, to his own needs.

This is the motivating force behind Some Changes, a touring

retrospective of Ligon’s past 18 years of work, which

comes to The Andy Warhol Museum on September 30: the way

Ligon has altered the cultural world around him, returning

time and time again to certain sources and subjects in

order to discuss perceptions of identity in the contemporary

world.

“Perhaps it doesn't make sense to say ‘self-portrait’ [in

reference to my artwork] anymore,” says Ligon. “Perhaps

it never did. I think in a world where the boundaries of

national, sexual, and racial identity are up for grabs,

who is to say what the real ‘I’ is? I am curious

about this breakdown in certainty. From the very beginning

my work has been positioned as self-portraiture; but it

was always quotation: someone else's ‘I.’”

Black, Male, and Gay

That something as seemingly simple as a self-portrait

could become so conceptual illustrates the complexity of

a modern life like Ligon’s. Born in the Bronx in

1960, Ligon grew up both African-American and gay throughout

the civil rights era, the black power movement, and an

exciting and volatile time for black pop culture. But,

as Ligon points out, the era that brought Zora Neale Hurston,

James Baldwin, and Richard Pryor together in his vocabulary

was not necessarily an easy one to navigate.

“I wasn't an artist in the ’70s,” says

Ligon, “I was simply ‘black, male, and gay,’ which

would have been hard for anyone to be in the ’70s.

“The things I learned in my neighborhood about being

a black American are things that I also read in Ellison

or Baldwin. But Ralph Ellison is not Richard Pryor, and

the way they talk about what it might mean to be a black

American vary widely. The range of things they articulated

informed my own thoughts on the subject.”

Some Changes introduces us to the pantheon of cultural

touchstones to which Ligon has returned throughout his

career that illustrate certain vagaries of identity. There’s

Richard Pryor, whose comedy provided Ligon’s generation

with a spokesman for its changing ideas of race in America,

in Ligon’s series, “Richard Pryor Paintings

(1993-2004).” Essays by Baldwin and Hurston and other

literature by the likes of Jean Genet provide Ligon with

the text for his etchings—often manipulated, blotted,

and darkened to near-illegibility.

And then there’s Andy Warhol, king of the New York

arts scene right as Ligon began his own art experimentation. “Warhol

has been a tremendous influence on me in that he was unconcerned

about switching from medium to medium,” Ligon says. “From

painting to film, from film into publishing, from figuration

to abstraction. Jean-Michel Basquiat's work is also important

to me because he is a poet, and he brought his love of

language to his canvases.”

The artwork of others has been as much fodder for Ligon’s

work as any other cultural touchstone. Ligon’s most

famous manipulation was his revision of photographer Robert

Mapplethorpe’s Black Book, a series of photos of

nude black men, done for the 1993 Whitney Biennial: Notes

on the Margins of the “Black Book,” in which

Ligon captions each photo with language from the likes

of Baldwin in order to change the photo’s meaning.

For another Some Changes work—the recent world wide

web project Annotations —Ligon returned to his theme

of changing the meaning of imagery through context. It’s

an online scrapbook of photos, primarily of African-American

families from the first two-thirds of the 20th century,

laid out with multiple levels of associations. A photo

of an infant is captioned “Future President of the

United States”; click on a picture of two women departing

a train, hat-boxes in hand, and a photo of the sheet music

to “Strange Fruit” appears; click a photo of

two women at a restaurant and hear Ligon singing disco

anthems.

Don’t expect to see more web work from Ligon anytime

soon, though.

“I am done with web-based work for now,” he

says. “It requires too many technicians; I like to

work solo. And I am not interested in learning programming

languages. Life is short!”

Co-curated by Wayne Baerwaldt and

Thelma Golden, Glenn Ligon: Some Changes is organized by

The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery at Harbourfront

Centre, Toronto.

With the generous support of The Andy

Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, The Horace Walter

Goldsmith Foundation,

Peter Norton Family Foundation, Albert & Temmy Latner

Foundation and Toby Devan Lewis.

Additional support is provided

by Hal Jackman Foundation, Judy Schulich, The Board Art

Foundation, Gregory R. Miller,

The Drake Hotel, The Linda Pace Foundation and Dr. Kenneth

Montague.