Back

The Mysteries of the Bog People Unearthed

By M.A. Jackson

Thanks to

scientific sleuthing, the “bog people”—the

mummified remains of our European forefathers—tell

us strange tales of life thousands of years ago.

A partially decomposed head is found near the Manchester,

England, home of a man whose wife disappeared 20 years

earlier. When initial testing reveals the head belonged

to a 30- to 50-year old European woman, police confront

the man who quickly confesses. A partially decomposed head is found near the Manchester,

England, home of a man whose wife disappeared 20 years

earlier. When initial testing reveals the head belonged

to a 30- to 50-year old European woman, police confront

the man who quickly confesses.

Sounds like an episode of

the ubiquitous CSI: Crime Scene Investigation TV shows,

right? But here’s the twist

that even CSI’s forensic experts could never have

dreamed up: Subsequent carbon 14 dating showed the head

to be 1,700 years old. Even so, Peter Reyn-Bardt—who

police had for some time suspected of killing his wife—went

to prison based on his confession.

That infamous head, discovered in 1983, is among the remains

of hundreds of “bog people” unearthed from

northern Europe’s peat bogs during the past 200 years.

Seven of these bodies and a host of artifacts associated

with them—from tools to jewelry—are showcased

in The Mysterious Bog People, debuting at Carnegie Museum

of Natural History on July 9. The exhibit provides a rare

glimpse into the life, customs, and religious beliefs of

Europeans living during the Stone, Bronze, and Iron ages.

Made

up of wet spongy ground—much like a marsh—that

fills with decaying mosses, a bog has chemical properties

that preserve hair and flesh (fingerprints were still visible

on several bodies). Thanks to those properties, the mummified

remains found in the bogs of Europe have allowed archaeologists

to extrapolate about the culture and belief system of the

northern Europeans who lived at the dawn of Christianity.

“

We can find out how they died, their age, sex, and even

the season of death based on pollen and insect pupae found

with the body,” says Sandra Olsen, curator of anthropology

at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “We can see

whether or not they had tattoos, what their last meals

were, what kind of parasites they had. We can even determine

blood type, height, and sometimes dental condition.”

Unfortunately,

many of the bodies tell a grisly story of death by violence:

bludgeonings, stabbings, hangings, and

probably drownings. Many individuals suffered a number

of these fates—what police today would call “overkill.” Through

the use of cutting-edge forensic science, the rather creepy

conclusion is that many “bog people” had been

ritually sacrificed.

Ritual and Superstition Meet Science

The people who inhabited northern Europe between 10,000

BC and 500 AD were a superstitious lot. Living in the

high, dry lands between bogs, they believed spirits and

gods dwelled in caves, in groves of trees, and especially

in watery places. In fact, the supernatural was so feared

that many bodies consigned to bogs were weighted or pinned

down to prevent their

spirits from rising to pursue the living. This is where

the bogeyman—the mythical creature that has scared

children into good behavior for centuries—was born.

The people who placed the bodies in the bogs called the

evil spirits

that they believed lived in the bogs the “boggymen.”

“

Sacrifice was done to curry favor with the gods—for

greater fertility for the crops, greater fertility for

the animals, and greater fertility for the women,” says

Olsen, the only Old World archaeologist at Carnegie Museums. “On

the flip side, sacrifice was also done to appease the gods

to prevent them from getting angry and inflicting punishment

such as famine or plagues.”

Although not a part of

the exhibit, one of the best-studied bog bodies is that

of England’s 2,500-year-old “Lindow

Man,” the poster boy for ritual sacrifice. Using

X-rays, CT-scans, scanning electron microscopy analysis,

and electron spin resonance spectroscopy, Lindow Man’s

remains revealed that at the age of 25 he had been killed

as part of a ritual sacrifice—bludgeoned and garroted

before having his throat cut. What’s more, researchers

learned that the ends of his beard were cut on both sides,

or “stepped,” indicating they had been trimmed

with shears or scissors and not a razor shortly before

his death—the first archaeological proof that Iron

Age northern Europeans possessed these cutting tools.

But

the most interesting clues were in his intestines: mistletoe

pollen—a sacred Celtic

plant—and

a small piece of charred oak cake, called bannock bread.

When Romans began invading the British Isle in 55 BC, they

reported that Iron Age Celts often performed ritual sacrifices

during “Beltain,” a spring festival that occurred

when mistletoe would have been in bloom. During these celebrations,

pieces of bannock bread—including one charred piece—were

doled out, and the soon-to-be lucky stiff who picked the

burnt piece became the sacrificial lamb. Olsen says mistletoe—slipped

into food or eaten willingly—might have acted as

a sedative, creating a tractable state. (Mistletoe has

long been administered as an antispasmodic, tonic, or narcotic.)

Olsen, who has

worked on weapons found deposited in a northern English

bog as well as on archaeological finds of prehistoric

sacrifices in Kazakhstan, was working at the British Museum

when Lindow Man arrived for analysis. “I didn’t

personally work on him, but my friends did,” she

says. “They did a fantastic job of analyzing every

aspect of him and publishing the results.

“

I remember the excitement when they found his navel…the

only Iron Age belly button ever found,” Olsen recalls. “And

it’s an innie!”

Non-Judgmental Learning

Roman historian Tacitus reported that northern Europeans

often punished deserters, social outcasts, law-breakers,

thieves, and prostitutes by hanging them. That may have

been the fate of The Mysterious Bog People’s “Yde

Girl.” Living in the first century Netherlands,

Yde Girl’s short life—she died at age 16—was

not a happy one. She suffered from scoliosis, a curvature

of the spine, which affected her walk; her woolen cape

was threadbare and oft mended, indicating poverty; and

she died violently—stabbed in the clavicle and

hung with a woolen cord that still encircled her neck

when she was uncovered in 1897.

Yde Girl may have been

punished for a crime or sacrificed—or

both. “They were very practical people,” says

Olsen of the early northern Europeans. “If they wanted

to get rid of someone they didn’t like, they may

have made a ritual sacrifice of them.”

Judging from

the items discovered in the bogs, researchers have discerned

that human sacrifices were probably the

exception and not the rule. The Mysterious Bog People showcases

400 less-grisly items that were offered up to the bogs’ spirits

and gods. Since most of these items are valuable and in

good condition, archaeologists think they were prized possessions

placed in bogs along travel routes to ensure safe passage

through the quicksand-like waters often frequented by thieves

and highwaymen. Items in the exhibit include a ceremonial

wind instrument called a lur, agricultural tools, weapons,

and a beautiful necklace of tin, faience, and amber beads.

The objects found in the bogs tell us much about how these

people worked, what materials they received in trade, and

how they adorned their bodies. And, yes, how they died.

But despite the physical evidence, some researchers will

try to explain-away the idea of ritual sacrifice. According

to Olsen, they rationalize that “nooses” could

have been necklaces that shrank in the bog’s water,

and “knife wounds” could have been made post-mortem

with peat-cutting machinery.

“

We try very hard not to put our value system on what we

find; we try not to be judges,” she says. “I

think some of the people who dispute the ritual sacrifice

angle just don’t want to think our ancestors could

have done something like that.”

The Bogs

Just as mysterious as the bodies found in the bogs are

the bogs themselves. Only two other environments preserve

human remains as well—arctic cold and dry deserts.

In

the 16th century, hundreds of years after Christianity

ended the pagan ritual sacrifices, Europeans discovered

that peat could be burned for fuel. The first

known discovery of a bog body occurred during peat harvesting in the late 1700s,

but there were surely earlier discoveries whose significance was overlooked

and the remains reburied.

“

Red Franz,” whose name came from the carrot-colored hue the bog water

turned his blonde hair, almost suffered that fate. When Franz was unearthed

in Germany 105 years ago, his body was so well preserved he was taken for

a recent murder victim. When his body wasn’t claimed, he was buried

in a local cemetery only to be dug up again five months later when scientists

at a local museum realized the error. Franz had indeed been a

murder victim—his throat was slashed—but he actually died at

age 25 between 200 and 400 AD.

How does a bog preserve human remains so well

that a millennium can pass without much effect? While cold freezes and

deserts dry, a bog pickles and tans. A bog’s stagnant

waters prevent flesh-decaying bacteria from growing and

its highly acidic waters preserve skin, hair, nails, and

even organs that tannin in the sphagnum

moss tans like

leather. Surprisingly, different bogs preserve things differently. In some,

only hair, skin, and hide or vegetable-based clothing (such as cotton and

flax) remain; while bones and teeth are eaten away. “Calcium-rich

bones and teeth need a more alkaline environment,” Olsen explains. “Some

of the bog bodies have few bones left. They’re just a hollow bag,

somewhat like a leather purse.”

Protected for hundreds of years in

a watery grave, a bog body can quickly begin to deteriorate once brought

to the surface. “Once the body is out of

the ground, then we have to worry about how to preserve it again,” says

Olsen.

The best method is freeze-drying, which removes moisture

from the organic material and prevents excessive shrinkage,

but bodies have

also been

re-tanned in oak

bark and then oiled with glycerin, lanolin, and cod liver oil to prevent

them from drying out. They can then be displayed—almost like

giving them a second life.

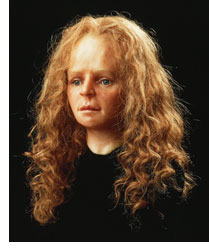

Another method of “reviving” these

people is through facial reconstruction, a procedure often utilized

by modern-day police investigators who’ve

found a decomposed John (or Jane) Doe. Using a well-preserved skull,

CT-scans, and sophisticated computer software, the face is rebuilt

layer by layer using clay or wax for soft tissue and artificial eyes

and hair. Another method of “reviving” these

people is through facial reconstruction, a procedure often utilized

by modern-day police investigators who’ve

found a decomposed John (or Jane) Doe. Using a well-preserved skull,

CT-scans, and sophisticated computer software, the face is rebuilt

layer by layer using clay or wax for soft tissue and artificial eyes

and hair.

The results are stunningly—and a little disturbingly—life-like.

The Mysterious Bog People features two such reconstructions—Yde

Girl and Red Franz. They almost appear ready to speak.

And if only they could…what stories they would tell.

Through the wonders of facial reconstruction,

the world

sees “Yde Girl.”

Carnegie Museum of Natural

History's presentation of The Mysterious Bog People was

made possible through generous grants from ANSYS, the

Inns on Negley, Jendoco

Construction Corporation, NOVA Chemicals, and the

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Promotional

support is

being provided by Citizens Bank, Duquesne University,

the Greater Pittsburgh Convention & Visitors

Bureau, and Walnut Capital. Media sponsors for the

exhibit

are KDKA-TV, Lamar Advertising, and Steel City Media.

The Mysterious

Bog People will be at Carnegie Museum of Natural

History through January 23, 2006. The exhibit was

produced in partnership by four major European

and Canadian museums: the Niedersächsisches

Landesmuseum in Hanover, Germany; the Canadian Museum

of Civilization in Gatineau, Canada; Glenbow Museum

in Calgary,

Canada; and the Drents Museum in Assen, Netherlands.

Back | Top |