COLOSSAL!

By M.A. Jackson

Its creation

more than a century ago was called a “colossal undertaking,”

and its residents were the most colossal creatures ever

to have roamed the earth. Dinosaur Hall: a history.

In 1898, three years after opening Carnegie Museums, Andrew

Carnegie asked museum Director William Holland to purchase

a dinosaur for display. Holland accepted the challenge while

warning his boss that buying, transporting, and mounting

such a specimen would be “the most colossal undertaking

of its kind in the history of

the world.”

Now, more than a century later, Carnegie Museum of Natural

History is about to embark on another colossal project:

updating and expanding its venerable and beloved Dinosaur

Hall. The project is no less ambitious than Andrew

Carnegie’s dream of creating a home for prehistoric

creatures in the dusty steel town where he made his fortune.

It will go beyond the mere presentation of dinosaur skeletons,

however, as it places the skeletal remains of dinosaurs,

mammals, fish, and the plant life from the Age of Dinosaurs

in realistic environments and scientifically accurate positions.

Groundbreaking is scheduled for March 2005.

“Carnegie

intrinsically understood the appeal of the dinosaurs and

how the public would react,” says Bill DeWalt, director

of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “He knew dinosaurs

would bring people in, and he wanted his museum to be to

be the center of scientific research about dinosaurs and

their world.” “Carnegie

intrinsically understood the appeal of the dinosaurs and

how the public would react,” says Bill DeWalt, director

of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “He knew dinosaurs

would bring people in, and he wanted his museum to be to

be the center of scientific research about dinosaurs and

their world.”

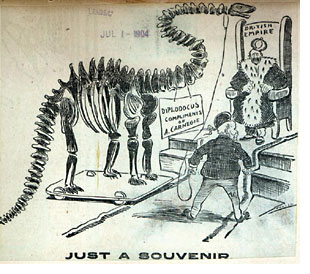

Right: What Andrew

Carnegie wanted, he got—and he wanted a dinosaur.

Here, then-museum Director William Holland gives dignitaries

a look at Diplodocus carnegii.

“Carnegie was of the ‘Oh my!’ value of

things,” says Mary Dawson, curator emeritus with Carnegie

Museum of Natural History. And no matter how jaded we think

we’ve become, the spectacle of a roomful of dinosaurs

never ceases to impress us.

“I’ve seen parents literally dash through the

other rooms in the museum with their children—they

just want to see the dinosaurs,” says Dawson, who

retired in 2003 after 30 years as the museum’s curator

of Vertebrate Paleontology, although she’s still active

in research. Surprisingly, the woman who has spent a good

part of her career talking about dinosaurs isn’t a

dinosaur expert at all. Her field of expertise is fossil

mammals. “I’ve never done research on a dinosaur,”

she says. “But dinosaurs are an occupation here for

any curator because of the public interest and the collections.”

For the Love of

Dinosaurs

As a child, John “Jack” McIntosh was one of

those kids who would race by other exhibits to see the dinosaurs.

A Wesleyan University physics professor emeritus, McIntosh

remembers the first time he visited Dinosaur Hall

at age five. “I fell in love immediately,” he

says.

As a teenager in the 1930s, McIntosh visited the museum’s

Paleontology department regularly—even during vacations—getting

to know the staff and the collections. Even though a Yale

professor convinced him to go into a field where he’d

earn more money, McIntosh continued to study the dinosaurs.

Today he is considered one of the world’s foremost

experts on sauropods (plant-eating dinosaurs with long necks

and tails), such as the museum’s Diplodocus carnegii.

Dinosaurs have enthralled people of all ages since they

were first discovered in the mid-1800s, and Carnegie was

no exception. The combination of the animals being a relatively

new phenomena, extremely rare, and colossal in size was

an intoxicating mixture for the industrialist.

“Carnegie always wanted the latest thing,” says

Betty Hill, retired collections archivist and now a volunteer

with the Museum of Natural History.

It was while visiting New York City that Carnegie opened

the newspapers to articles touting the Wyoming discovery

of a Brontosaurus giganteus. Carnegie immediately

sent the New York Post article to William Holland, with

a note “can you buy this for Pittsburgh—try…get

an offer...hurry.” Hill has the note, and many others,

scanned into the archives that she continues to painstakingly

fill.

Hill, who was hired by Mary Dawson in 1975 to help archive

the museum’s vast collections, probably knows the

story of Carnegie’s dinosaurs better than anyone,

having spent the last three years electronically storing

countless documents into the museum’s archives, including

old letters from Carnegie to his staff.

With a wealth

of knowledge and experience between them are Mary Dawson

(left), curator of Vertebrate Paleontology for over three

decades and now curator emeritus, and Betty Hill, retired

collection manager, whose association with the Museum of

Natural History has spanned 30 years.

PHOTO: RIC EVANS

Pay Dirt

Holland, always eager to please his boss, did hurry—fulfilling

Carnegie’s request within a year.

He spent the first six months trying to buy Brontosaurus

giganteus—which later turned out to be only a

femur. Finally admitting defeat, Holland moved his bone-digging

team 20 miles away to another site in the Morrison Formation

in Wyoming, hoping to find another dinosaur. On July 4,

1899, they hit pay dirt. In the months and years ahead,

they would send so many crates of fossils to Pittsburgh—including

the bones of three partial Diplodocus specimens—that

the museum installed railway tracks in its basement to facilitate

delivery.

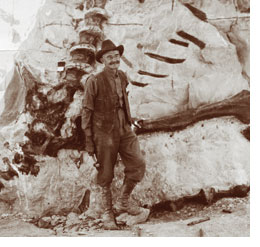

Left:

Earl Douglas, Carnegie bone hunter, at work. Left:

Earl Douglas, Carnegie bone hunter, at work.

Before becoming director of Carnegie Museums, Holland,

a Princeton graduate proficient in several languages, had

been pastor of Oakland’s Bellefield Presbyterian Church

and chancellor of Western University of Pennsylvania (now

the University of Pittsburgh). While he was self-taught

in paleontology, Holland had a thirst for scientific knowledge.

“Holland learned an awful lot,” says McIntosh.

“His later papers were quite good.” Dawson adds

that while Carnegie had the funds, Holland “was important

in understanding what was found.” What’s more,

Holland used Carnegie’s money to recruit major talent,

including Arthur Coggeshall, a fossil preparator, and Jacob

Wortman, the museum’s first curator of Vertebrate

Paleontology—both hired away from the American Museum

in New York. “Holland got a very fine staff of very

experienced men,” says McIntosh. “Coggeshall

was one of the best preparators of his time.”

When Wortman left the museum in 1900, Holland hired Princeton

Paleonto-logist John Bell Hatcher, who invented the excavation

grid system still used by paleontologists in the discovery

and study of dinosaur fossils. “Hatcher was a very,

very fine paleontologist,” says McIntosh.

It was Hatcher who dubbed the Carnegie team’s first

major find—a colossal sauropod—Diplodocus

carnegii “in recognition of Carnegie’s

interest in vertebrate paleontology.” The longest

known dinosaur at the time (its reign was later usurped

by Brachiosaurus), the Diplodocus is a

type specimen—the first of its kind found and the

basis for the species’ original description.

While

the $5 million museum expansion to house the dinosaur was

underway, King Edward VII saw an illustration of Diplodocus

carnegii and requested that Carnegie find one for the

British Museum. Knowing such a task would be nearly impossible,

Carnegie offered the king a Diplodocus carnegii

cast. Once mounted in England—two years before the

original would debut in Pittsburgh—requests poured

in. As a gesture of goodwill and scientific cooperation,

Carnegie (and later his wife) gave casts of his namesake

to 12 museums around the world, making Diplodocus carnegii

one of the world’s most seen dinosaurs. While

the $5 million museum expansion to house the dinosaur was

underway, King Edward VII saw an illustration of Diplodocus

carnegii and requested that Carnegie find one for the

British Museum. Knowing such a task would be nearly impossible,

Carnegie offered the king a Diplodocus carnegii

cast. Once mounted in England—two years before the

original would debut in Pittsburgh—requests poured

in. As a gesture of goodwill and scientific cooperation,

Carnegie (and later his wife) gave casts of his namesake

to 12 museums around the world, making Diplodocus carnegii

one of the world’s most seen dinosaurs.

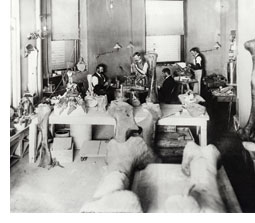

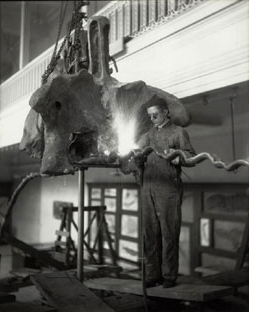

All the casts, as well as the originals, were mounted using

an ingenious system created by Coggeshall in which dinosaur

vertebrae are strung along one iron rod—using Carnegie

steel, naturally. Bones were attached with steel as unobtrusively

as possible. Mary Dawson says the mounting “is a work

of art itself.”

Bones, Bones,

and More Bones

In 1909, thanks to Carnegie’s annual $10,000 add-on

to the museum’s paleontology budget, Paleontologist

Earl Douglass—often referred to as “the King

of Collectors”—discovered one of the largest

caches of dinosaur bones ever found in the Morrison Formation

near Jensen, Utah. Designated Dinosaur National Monument

in 1919, the site contained enough dinosaur bones to keep

crews excavating year-round for 13 years.

Of the 20 mountable skeletons found, six were erected in

Dinosaur Hall between 1915 and the early 1940s:

Apatosaurus louisae (a.k.a. bronto-saurus),

Dryosaurus altus, Allosaurus fraglisi, a juvenile

Camarasaurus (the most complete sauropod skeleton

ever found), Stegosaurus ungulatus, and Camptosaurus

dispar. The Apatosaurus louisae, a type specimen,

was named after Carnegie’s wife, Louise. A more unusual

gift from a husband to his wife is difficult to imagine.

Also

difficult to imagine is what Carnegie’s men felt while

unearthing the dinosaurs. But Betty Hill, who wore many

hats during her 28 years with the museum, may best sum up

their feelings when recalling the two dinosaur expeditions

that she participated in during her tenure. “As we

were digging up bones, I kept thinking: ‘These are

the first human eyes that have ever looked at these bones.

The first.’” Also

difficult to imagine is what Carnegie’s men felt while

unearthing the dinosaurs. But Betty Hill, who wore many

hats during her 28 years with the museum, may best sum up

their feelings when recalling the two dinosaur expeditions

that she participated in during her tenure. “As we

were digging up bones, I kept thinking: ‘These are

the first human eyes that have ever looked at these bones.

The first.’”

According to Hill, about 70,000 specimens from those digs

have been catalogued—many of which she personally

entered into the computer system. “There are still

boxes and boxes of bones that havn’t been identified,”

she says.

In the years after the Utah digs ceased in 1923, Carnegie

Museum of Natural History purchased several dinosaurs, including

Tyrannosaurus rex (T. rex) and Protoceratops

andrewsi.In the 1980s, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology

David Berman excavated the remains of the museum’s

first Triassic dinosaur, Coelophysis, in New Mexico.

Of the 15 dinosaurs currently displayed in Dinosaur

Hall, five are type specimens.

But as new and more complete dinosaurs are unearthed and

studied, long-held ideas about how dinosaurs lived and looked

are altered, necessitating changes to the display of dinosaurs.

For instance, in 1978, Berman and McIntosh proved that in

1934 a Camarasaurus head had been mis-

takenly attached to Apatosaurus louisae, which

had been headless for more than 20 years. It was quickly

replaced with a cast of the correct skull.

Lore, Legend,

and Real History

Correcting history through science isn’t always a

popular thing, however. Legends die hard—such as the

legend of T. rex being a fierce, Godzilla-like

predator.

That’s

how T. rex was depicted in Dinosaur Hall’s

old Tyrannosaurus rex mural. Created in 1949 by

painter Otmar Von Fuhrer, the giant mural was commissioned

to complement the skeleton purchased in 1942 from the American

Museum. It loomed from the darkness, intimidating and exciting

children and adults alike for decades. But as paleontologists

researched T. rex using computer simulations, ichnites (fossil

tracks), and more complete skeletons, they realized the

mural’s depiction of T. rex’s anatomy

and surroundings were incorrect. That’s

how T. rex was depicted in Dinosaur Hall’s

old Tyrannosaurus rex mural. Created in 1949 by

painter Otmar Von Fuhrer, the giant mural was commissioned

to complement the skeleton purchased in 1942 from the American

Museum. It loomed from the darkness, intimidating and exciting

children and adults alike for decades. But as paleontologists

researched T. rex using computer simulations, ichnites (fossil

tracks), and more complete skeletons, they realized the

mural’s depiction of T. rex’s anatomy

and surroundings were incorrect.

Left: The process

used to mount the bones of the dinosaurs—using specially

molded Carnegie steel—is still called “a work

of art” today.

In the late 1990s, the museum removed the mural, much to

the chagrin of many Pittsburghers. It was eventually replaced

by a new painting—from renowned dinosaur artist Michael

Skrepnick— depicting T. rex in what is now considered

the correct horizontal position. Prohibitive remounting

costs, however, necessitated leaving the skeleton improperly

sitting up.

T. rex is not the only dinosaur that will be remounted

in a scientifically accurate, active pose during the upcoming

renovation. Scientists now believe sauropods did not drag

their tails, so Diplodocus and his sauropod friends

will receive makeovers as well. (The fiberglass replica

of “Dippy” erected outside the museum in 1999

is correctly posed with tail in the air.)

The expansion will also provide space for several dinosaurs

kept in storage, the museum’s rich collection of mammals,

fish, and plant fossils, as well as new dinosaur discoveries.

DeWalt specifically mentions the work of the museum’s

new Assistant Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Matt Lamanna,

who at the ripe old age of 25 discovered the sauropod Paralititan

in Egypt. DeWalt hopes that after the skeleton is studied,

a cast will be made for the museum and the original returned

to Egypt. Fittingly, the creation of that cast would likely

employ many of the same techniques created over 100 years

ago by the ingenious Carnegie team.

Almost 100 years after Dinosaur Hall opened, its

famed dinosaurs are still attracting crowds. And Carnegie

Museum of Natural History—recognized for having one

of the world’s largest collections of dinosaur fossils—is

still on the cutting-edge of scientific research, global

cooperation, and education.

“We continue Andrew Carnegie’s interests and

visions,” DeWalt says. And the world continues to

be fascinated.

Back | Top |