Above left: Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Marcel Duchamp (detail), 1966, 16mm film, black and white, silent,

4 minutes at 16 frames per second, © 2010 The Andy Warhol Museum. All rights reserved

Above right: Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, 1986, Collection of The Andy Warhol Museum

© AWF/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

|

|

Twisted Pair

By Cristina Rouvalis

A new exhibition at The Warhol explores the artistic kinship between two of contemporary art’s favorite bad boys—Andy Warhol and his hugely influential predecessor, Marcel Duchamp.

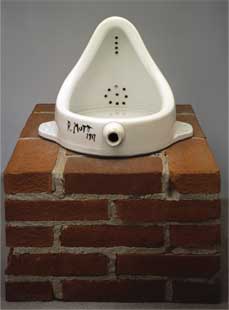

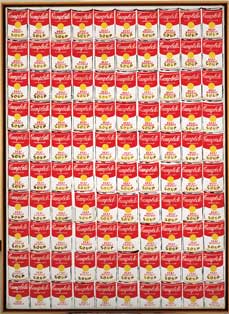

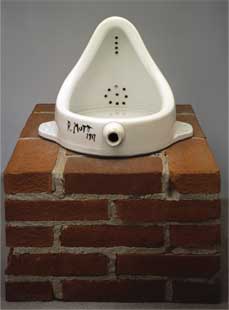

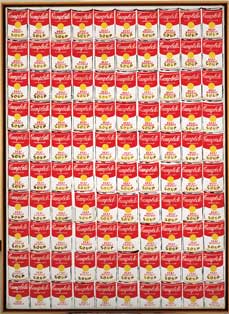

Forty-five years before Andy Warhol exhibited his paintings of Campbell’s Soup cans, Marcel Duchamp found art in an even less likely source—a urinal. He titled the white porcelain figure Fountain and presented it as a new form of art—a “ready-made”—to the American Society of Independent Artists for its 1917 exhibition in New York.

Taking a mundane object and turning it into an unforgettable work of art was the signature of both artists.

The rules stated that anyone who paid the nominal entry fee could exhibit work. But as it turned out, the art group wasn’t independent-minded enough to accept the urinal, which Duchamp submitted under the pseudonym R. Mutt. The rules stated that anyone who paid the nominal entry fee could exhibit work. But as it turned out, the art group wasn’t independent-minded enough to accept the urinal, which Duchamp submitted under the pseudonym R. Mutt.

A fake name and scandalous entry weren’t his only tricks, however. Duchamp was also a member of the show’s jury. In the end, he unsuccessfully lobbied other members to accept the Fountain, which decades later became one of the world’s most famous images of contemporary art.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917 © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp; Photo: Moderna Museet/Stockholm

Taking a mundane object and turning it into an indelible work of art was the signature of both Duchamp and Warhol. Duchamp greatly influenced Warhol, and the many connections between these two contemporary art powerhouses can be seen in the exhibition Twisted Pair: Marcel Duchamp / Andy Warhol, on view at The Andy Warhol Museum through September 12. The show includes a copy of the Fountain. The original was lost soon after it was rejected in 1917. But Duchamp approved certain copies and even repainted the signature “R. Mutt /1917” so that they were more authentic.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962, Collection of Albright-Knox Art Gallery

© AWF/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While many have written about the duo’s artistic kinship, Matt Wrbican, The Warhol’s archivist and curator of the exhibition, believes this is the first exhibition devoted exclusively to the works of Duchamp and Warhol, whom he likens to the DaVinci and Michelangelo of contemporary art.

“They were both troublemakers,” Wrbican says. “They thought art could be fun and playful. But they were both very serious. They were hugely influential. You can see many things contemporary artists do today referencing both Duchamp and Warhol.”

Towards the end of Duchamp’s life and as Warhol’s star was rising in the 1960s, the two occasionally would run into each other. Warhol had Duchamp’s name in his address book, but they were believed to be more acquaintances than friends.

Artistic Anarchy

The man who influenced Warhol so much referred to himself as an “an-artist,” a play on anarchist.

In 1913, Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase became a national scandal.

“Warhol picked up that bad-boy attitude from Duchamp,” Wrbican asserts. A possible case in point: While a student at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, Warhol submitted a portrait of himself picking his nose, which was rejected for the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh’s 1949 Annual. A college classmate recalled that he also made white-on-white drawings, defying a basic premise of visual art. “Warhol picked up that bad-boy attitude from Duchamp,” Wrbican asserts. A possible case in point: While a student at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, Warhol submitted a portrait of himself picking his nose, which was rejected for the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh’s 1949 Annual. A college classmate recalled that he also made white-on-white drawings, defying a basic premise of visual art.

There were other similarities. Both men loved the night life and were artist-celebrities of their respective times. Women threw themselves at Duchamp, a ladies’ man, and at Warhol, without realizing he was gay.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, 1913,

© 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

Still, Duchamp and Warhol differed sharply in their backgrounds and their approach to the contemporary art business. Duchamp was the debonair Frenchman who grew up in a comfortable middle-class family in France, with great galleries and artistic role models around him. Both his grandfather and two brothers were artists. He borrowed money from his father, a successful notary, to launch his career.

In contrast, Warhol was the sickly son of a Pittsburgh laborer who had to scrimp and save to send his child to art school at Carnegie Tech in 1945. “That made Warhol a real tightwad,” Wrbican says. “It made him obsessed with earning money. His famous quote was, ‘Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.’” In contrast, he says, “Duchamp was a good businessman but he wasn’t making art and selling it for great sums of money like Warhol.”

Duchamp, the Lovable Intellectual

Both artists were very concerned about their place in art history. Duchamp made his first mark on history during the Armory Show in New York City in 1913, when he submitted a painting called Nude Descending a Staircase. Unknown to him because he had stayed behind in France, the painting became a national scandal and drew huge crowds. It received so much press that it was lampooned in the cartoons. Never mind that you could barely make out the human body in this Cubist painting. In fact, ARTnews magazine offered $10 to any reader who could point out the nude figure, and President Roosevelt compared it to a Navajo rug.

“No one—I mean no one—had ever depicted a nude descending a staircase before,” Wrbican says. “Up to that point, nudes were seen as the Greek classical ideals, reclining or standing.” A critic called the painting “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

When he arrived in New York two years later, Duchamp was greeted by reporters. He was tickled by his instant celebrity, and, like Warhol, he leveraged it into something bigger. An accomplished chess player, Duchamp was a true intellectual, and he gladly gave lectures on art, including a famous talk on the creative process. He was also engaging and forthcoming to the press. Warhol mumbled to reporters, putting on a coy, campy, even dumb persona that let reporters reflect back whatever they wanted to see.

“Duchamp was innately lovable,” says Michael Taylor, curator of modern art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which has a large collection of Duchamp’s work, with four pieces on loan for Twisted Pair. “He was this incredibly good-looking Frenchman, very suave and very intellectual but never in a dry way. People wanted to be around him, even if they didn't understand what he was doing.”

As his reputation grew, Duchamp was asked to judge prestigious exhibitions, including the 1959 Carnegie International at Carnegie Museum of Art. Wrbican discovered this Pittsburgh connection serendipitously, having come across a January 26, 1959, issue of LIFE magazine at a used book store. He bought it because of a personal interest in the date, and, upon opening it, Wrbican was delighted to find a story about the exhibition accompanied by a photo of Duchamp and his fellow jurors.

Warhol, the Self-Made Icon

Duchamp made far fewer works of art than Warhol, who was famously prolific. “He thought after a while artists repeated themselves,” Wrbican says. “It was a trap he wanted to avoid.” But later in his career, Duchamp decided to replicate his art work in a new form he called Boîte-en-Valise, or box in a suitcase. He hired craftsmen to make 69 tiny replicas of his work for each of the 300 Boîtes. “It was a bit like a toy, but also a mini-retrospective,” Wrbican says.

Warhol, of course, had no problem repeating himself, hiring assistants to help him churn out his Pop Art in his New York studio, The Factory. As Duchamp grew older, he encouraged the experimentation of a younger generation of artists. “Even though he was in his 70s and 80s, he wasn't defending an old position. He was very comfortable in his own skin,” Taylor adds. “He was a catalyst for a whole generation of artists who wanted to go beyond the academy.”

The fact that Duchamp rejected Impressionism was very freeing to the young Warhol, who attempted to crack the New York art world while watching macho Abstract Expressionist painters like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

“For Warhol, I think the dilemma was how he was going to be an artist when machismo was celebrated,” Taylor says. “Warhol looked at Duchamp’s reaction to Abstract Expressionism and saw a way out.”

Clearly enamored by Duchamp, Warhol took his predecessor’s radical ideas about everyday, ready-made objects and made them his own by applying them to consumer and celebrity culture. He owned about two dozen Duchamp works, including a copy of the Fountain and two of the Boîtes. Surprisingly, though—or perhaps not so surprisingly—he wouldn’t admit his admiration for the older artist when interviewed about him. Warhol merely said Duchamp was a nice man, but maybe not that important as an artist.

“I think he felt like he didn’t want to be known as Duchamp, Jr.,” Wrbican says.

But if Warhol was coy about Duchamp’s talents, Duchamp praised Warhol. “I really like Warhol's spirit,” he said. “He’s not some painter. He’s a filmeur (French for cameraman), and I like that very much.”

Making the Common Something Else

In 1966, Duchamp found himself behind Warhol’s camera in one of his famous Screen Tests, his three-minute film portraits (see page 28). Duchamp had invited Warhol to a fundraiser for The American Chess Foundation and Warhol knew that Duchamp was good at holding a stare. So he tried to trip him up by asking sexy Italian actress Benedetta Barzini to stroke his leg as the camera rolled. A faint smile played on Duchamp’s lips as the woman cuddled him provocatively, but he didn’t lose his composure.

“He is a little uncomfortable,” says Taylor of Duchamp’s reaction. “He wants to drop his guard, but Duchamp is not going to let Warhol win. It becomes a battle of wills between them.”

The pair’s playful side also came out in their alter egos. Duchamp often referred to himself as his female persona Rrose Sélavy. Warhol played with the idea of renaming himself John Doe, and occasionally it stuck. John Lennon and Yoko Ono once mailed him a letter addressed to John Doe.

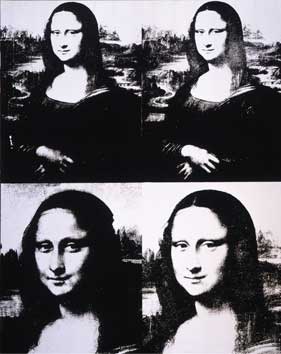

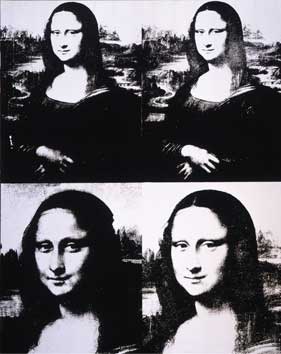

Mona Lisa was another common theme of the two artists. Duchamp created another outcry when he made a lithograph of the famous DaVinci painting and drew a goatee and moustache on her smiling face. The public was not amused. Warhol created his famous silkscreens of the Mona Lisa after the painting arrived in the United States in 1962. Enamored with the French-speaking First Lady Jackie Kennedy, the French government had loaned out the Renaissance icon to the National Gallery in Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Warhol took his silkscreened image of the painting straight from the museum catalog. Mona Lisa was another common theme of the two artists. Duchamp created another outcry when he made a lithograph of the famous DaVinci painting and drew a goatee and moustache on her smiling face. The public was not amused. Warhol created his famous silkscreens of the Mona Lisa after the painting arrived in the United States in 1962. Enamored with the French-speaking First Lady Jackie Kennedy, the French government had loaned out the Renaissance icon to the National Gallery in Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Warhol took his silkscreened image of the painting straight from the museum catalog.

Andy Warhol, Mona Lisa, ca. 1979, Collection of The Andy Warhol Museum

©AWF/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The pair shared a muse: Duchamp made a lithograph of the Mona Lisa and drew a goatee and a moustache on her smiling face, creating a public outcry. Warhol created his famous silkscreens (above) of the famous DaVinci painting after it arrived in the United States in 1962.

As Twisted Pair reveals, there are many common threads between the two artists, namely artworks that center around money, typewriters, and other ordinary, everyday objects—urinals, included. Duchamp’s work on view is on loan from museums and dealers around the world, including 20 from Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, and 18 works from New York art dealer Francis Naumann. Most are on display in Pittsburgh for the first time. As Twisted Pair reveals, there are many common threads between the two artists, namely artworks that center around money, typewriters, and other ordinary, everyday objects—urinals, included. Duchamp’s work on view is on loan from museums and dealers around the world, including 20 from Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, and 18 works from New York art dealer Francis Naumann. Most are on display in Pittsburgh for the first time.

Wrbican imagines that Warhol would have liked his work to be displayed alongside Duchamp’s. “I think he would have considered it a great honor.”

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q., 1919 © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp; Photo: Moderna Museet/ Stockholm

Duchamp died in 1968 at the age of 81. Warhol died in 1987 at the age of 58. But the two live on in the impact they continue to have on the art world they helped shape decades ago.

“You cannot look at a can of Campbell’s Soup in any grocery store and not think of Warhol,” Taylor says. “Any man standing in front of a urinal will think of Duchamp. Both of them took common, everyday objects and transcended their mundane status to become unforgettable works of art.”

|

The rules stated that anyone who paid the nominal entry fee could exhibit work. But as it turned out, the art group wasn’t independent-minded enough to accept the urinal, which Duchamp submitted under the pseudonym R. Mutt.

The rules stated that anyone who paid the nominal entry fee could exhibit work. But as it turned out, the art group wasn’t independent-minded enough to accept the urinal, which Duchamp submitted under the pseudonym R. Mutt.

“Warhol picked up that bad-boy attitude from Duchamp,” Wrbican asserts. A possible case in point: While a student at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, Warhol submitted a portrait of himself picking his nose, which was rejected for the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh’s 1949 Annual. A college classmate recalled that he also made white-on-white drawings, defying a basic premise of visual art.

“Warhol picked up that bad-boy attitude from Duchamp,” Wrbican asserts. A possible case in point: While a student at Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, Warhol submitted a portrait of himself picking his nose, which was rejected for the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh’s 1949 Annual. A college classmate recalled that he also made white-on-white drawings, defying a basic premise of visual art. Mona Lisa was another common theme of the two artists. Duchamp created another outcry when he made a lithograph of the famous DaVinci painting and drew a goatee and moustache on her smiling face. The public was not amused. Warhol created his famous silkscreens of the Mona Lisa after the painting arrived in the United States in 1962. Enamored with the French-speaking First Lady Jackie Kennedy, the French government had loaned out the Renaissance icon to the National Gallery in Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Warhol took his silkscreened image of the painting straight from the museum catalog.

Mona Lisa was another common theme of the two artists. Duchamp created another outcry when he made a lithograph of the famous DaVinci painting and drew a goatee and moustache on her smiling face. The public was not amused. Warhol created his famous silkscreens of the Mona Lisa after the painting arrived in the United States in 1962. Enamored with the French-speaking First Lady Jackie Kennedy, the French government had loaned out the Renaissance icon to the National Gallery in Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Warhol took his silkscreened image of the painting straight from the museum catalog.  As Twisted Pair reveals, there are many common threads between the two artists, namely artworks that center around money, typewriters, and other ordinary, everyday objects—urinals, included. Duchamp’s work on view is on loan from museums and dealers around the world, including 20 from Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, and 18 works from New York art dealer Francis Naumann. Most are on display in Pittsburgh for the first time.

As Twisted Pair reveals, there are many common threads between the two artists, namely artworks that center around money, typewriters, and other ordinary, everyday objects—urinals, included. Duchamp’s work on view is on loan from museums and dealers around the world, including 20 from Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, and 18 works from New York art dealer Francis Naumann. Most are on display in Pittsburgh for the first time.