Winter 2009

Winter 2009|

“The result is a rich and compelling presentation that

is roughly chronological, mixing works from the same time period created in different locations to show how styles migrated from country to country and continent to continent. ” Photo: Joshua Franzos |

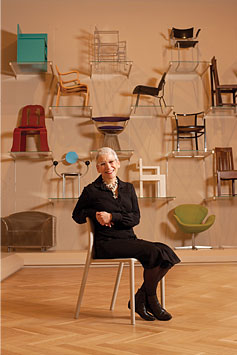

The legendary curator and art historian William Rubin used to say that exhibitions come and go, but the collection is the true measure of a museum. With that in mind, I am especially pleased to have arrived in Pittsburgh as the new Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art in time for the reopening of the Ailsa Mellon Bruce Galleries for decorative arts and design. This is an occasion about which the entire community can be proud. The legendary curator and art historian William Rubin used to say that exhibitions come and go, but the collection is the true measure of a museum. With that in mind, I am especially pleased to have arrived in Pittsburgh as the new Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art in time for the reopening of the Ailsa Mellon Bruce Galleries for decorative arts and design. This is an occasion about which the entire community can be proud. Nearly 3,000 objects from the collection of Pittsburgh philanthropist Ailsa Mellon Bruce came to Carnegie Museum of Art following her death in 1969, greatly augmenting the museum’s holdings of decorative arts and design. Over the ensuing four decades a series of sensitive and intelligent curators added to that gift, in the process assembling an excellent collection of fine furniture, porcelain, and other useful objects. The current installation, in newly renovated state-of-the-art galleries, is an expanded installation of these stunning and innovative works. More work went into this installation than is immediately obvious. Jason Busch, The Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts, with Rachel Delphia, assistant curator, spent several years examining every work in the collection to determine the selection for display. Jason also added to the collection where he saw lacunae. The result is a rich and compelling presentation that is roughly chronological, mixing works from the same time period created in different locations to show how styles migrated from country to country and continent to continent. Amid the English, French, and German objects are many works from the United States, and from western Pennsylvania in particular. When Andrew Carnegie famously charged the staff at his new institution with acquiring the old masters of tomorrow, he was thinking of the fine arts, predominantly painting and sculpture. Carnegie overlooked the disciplines of decorative arts and design, perhaps for the very same qualities that give them broad appeal. Because everyone uses furniture, silverware, and dishes, it becomes possible to imagine living with Joseph de Saint-Germain’s Rococo clock of c. 1750, pouring tea from the silver-plated and ivory British “tea machine” of c. 1810, or sitting in Hector Guimard’s 1904 chair. And with the objects comes a sense of their time. Nowhere in the galleries is the possibility for time travel more palpable than with the installation of the PicNic suite, originally housed in a classically styled mansion built in Pittsburgh in the 1830s. The gilded and faux-rosewood-grained furniture is influenced by ancient Greek and Egyptian styles. Seen in the galleries, against a muted life-size elevation drawing of the parlor at PicNic, they are like a dream or memory of another era. Carnegie’s approach to collecting meant that much of the museum’s holdings would date from the late 19th century to the present. Our decorative arts collection, however, stretches back to before 1750. This has as much to do with the community as the curators who have served the museum over the decades. It is a collection that, in large part, Pittsburgh built. Please enjoy it.  Lynn Zelevansky Henry J. Heinz II Director Carnegie Museum of Art |

Also in this issue:

The Art of Daily Life · Putting the Popular in Science · Welcome · Clearing a New Path · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Lynn Zelevansky · Field Trip: For the Birds · Artistic License: Break-Out Performance · About Town: Social Science · Science & Nature: The Lord of the Flies · Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |