|

||||||

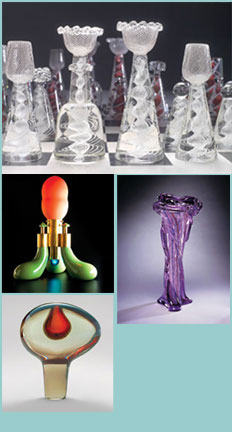

| Everything old is new again, as Pittsburgh celebrates artistry rooted in one of the region’s great but sometimes-forgotten industrial traditions. |

Long before it was the steelmaking capital of the world, Pittsburgh ruled as the center of industrial glassmaking. Now, as the region is poised to become a national leader in the glass arts, an inspired community of glassmakers and arts organizations—including Carnegie Museum of Art—have come together to celebrate Imagine if western Pennsylvania’s favorite football team had opted for a nickname inspired by a local industry that for decades once rivaled and even surpassed Big Steel. Something like the Pittsburgh Blowers. And just how tough could a Glass Curtain defense really be?Might have happened, you know. Because for nearly 150 years, Pittsburgh was the glass-making capital of America, producing nearly half of the country’s bottles, windows, street lamps, jars, and nearly anything else made from superheated molten sand that had been molded, pressed, or blown into a variety of shapes. Let’s just say that for the fans in the stands, it’s a good thing that Art Rooney Sr. settled on the Steelers. Still, the region’s role in the history of industrial glassmaking is every bit as important and pivotal as its steelmaking past. In fact, long before Andrew Carnegie and other 19th-century entrepreneurs made Pittsburgh the Iron City, glass was king. Now, more than 200 years after the first glassmaking shops sprung up on what is today the city’s South Side, glass is enjoying an artistic comeback—and its heritage and future are being celebrated around town like never before. Throughout the remainder of the year Pittsburgh Celebrates Glass!, a nonprofit initiative working to enhance the city’s image locally and beyond, will bring together more than 70 partners from the local arts community, business world, and academia to sponsor a multitude of glass-related events. Anchoring the festivities is a stunning exhibit at Phipps Conservatory of extraordinary glass garden sculptures hailing from glass master Dale Chihuly’s studios near Seattle. This year-long celebration is expected to lure nearly 400,000 residents and visitors, and contribute more than $20 million to the local economy, according to Pittsburgh Celebrates Glass!. Across the East End, in Garfield, the Pittsburgh Glass Center is showcasing its premiere international exhibition of emerging Japanese artists working in glass. And closer to home, Carnegie Museum of Art is hosting Viva Vetro! Glass Alive! Venice and America, a comprehensive review of how Venetian glass artists and techniques influenced their American counterparts during the past half century and vice versa. “Pittsburgh Celebrates Glass! provides us with a perfect opportunity to partner with others in the arts community, which we’re keen to do,” says Sarah Nichols, curator of Viva Vetro! and Pittsburgh Glass Center board president. “It gives us a chance to showcase our glass collection and promotes the Museum of Art’s interest in glass. All of the organizations involved hope that this celebration will spark an interest in glassmaking and collecting in the city for the long term.”

Location, Location, LocationFor most of its history, Pittsburgh seems to have found itself in the right place at the right time. In 1753, a young British colonel named George Washington spied the green triangle of land between the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers and dubbed it “extremely well situated for a fort.” About 40 years later, a couple of savvy businessmen, James O’Hara and Isaac Craig, viewed the city as the perfect place to set up a glassmaking factory at a location that’s now the Duquesne Incline parking lot near Station Square. The proximity of navigable waterways, abundant coal, and riverbed sand created perfect conditions to nurture an industry that grew to more than 75 glass manufacturers on the South Side during the 19th century. As plastics, aluminum, and other materials replaced glass as the product of choice for bottles and other applications, increasing labor and natural resources costs all but snuffed out the local industry. Plants closed. Furnaces went cold. Thousands lost the only jobs they, and many others in their families, ever knew. Still, the spirit of the region’s industrial glassmaking past burns on. In Swissvale, the Kopp Glass Company continues to make glass for railroad lanterns, a product line since the company started in 1926. “Our business certainly has changed since then,” says Hugh Reed, the company’s director of technical services. “Today, our primary business is the aircraft industry. We make glass for the Boeing 787, night vision filters for cockpit interiors, and glass for the space shuttle. But we also make glass for the red lanterns on the back of Amish buggies.” Local businessman Bill Kelman is stepping up to the challenge of reviving Glenshaw Glass and L.E. Smith—two stalwarts that ranked among the region’s biggest glass firms in their heydays. “There are a lot of people who come to the Pittsburgh Glass Center and tell me that their fathers and grandfathers worked in local glass factories,” says Karen Johnese, the center’s executive director. “It’s great to help them reconnect with the area’s glass history, and at the same time tell them that there’s so much innovative work going on here.” A Great Glass Leap Forward But nostalgia isn’t the only fuel behind the collaborative effort to recognize the city’s past involvement in glassmaking. The real goal of Pittsburgh Celebrates Glass! is delivering economic dividends to the region—now and in the future. “Pittsburgh Celebrates Glass! is a way of pointing out to people that the city is once again looking to be a leader in glass,” says Marguerite Jarrett Marks, program director of Pittsburgh Celebrates Glass!. “Only this time glass art will be leading the way.” “Pittsburgh Celebrates Glass! is a way of looking backwards and forwards,” says Nichols. “Backwards in honoring the industry’s past, and forwards as far as the city’s future in glass from an artistic perspective. This is a starting point for growth that goes beyond the arts community.” The Italian ConnectionNo other city in the world matches Venice for the sheer quality of glass produced by its craftsmen. So it’s no coincidence that Carnegie Museum of Art’s upcoming glass exhibition looks at the connections that build bridges between the Italian city, American glass artists, and Pittsburgh. Running through September 16, Viva Vetro! is a survey of Venetian art glass and its imprint on the American Studio Glass movement from about 1950 to the present. “The Venetian exhibition is very important for Pittsburgh and the Museum of Art,” says Nichols. “It helps the museum by establishing it as having an interesting, significant, and important glass collection. But the show also reveals how Venetian influences transformed the way American glass artists work today.” Long protective of its glassmaking secrets and wary of foreigners, Venice—or, more accurately, the island of Murano—gradually opened its doors to outsiders, beginning in the mid 1950s. Within a decade, American artists like Dale Chihuly were applying to the glass factories on Murano for an opportunity to train with the celebrated maestros. Certainly talented, Chihuly and other Americans often lacked the technical expertise of their Venetian counterparts. On Murano, they honed their technique and returned to the United States to teach others—completing that bridge of countries, cultures, and crafts. Nichols says that Venice’s history as a trading city-state exposed it to accents from around the world, many of which can be identified in the glass produced there. The 125 pieces in Viva Vetro!, including work by Chihuly, reveal how those Venetian influences transformed the work of American glass artists. In turn, the exhibition offers the Museum of Art the perfect opportunity to showcase its growing collection of glass art. “The museum started collecting contemporary glass during the early 1980s,” says Nichols, who is also the museum’s former chief curator and curator of decorative arts. “It continued to buy glass throughout the decade, but not in a big way. The real turning point was in the mid-1990s when Bill and Maxine Block gave the museum pieces from their collection. A few years later, they added more. Then in 2002, we held an exhibition of the Block collection, which resulted in them giving the museum many more works. Their generosity inspired the Museum of Art to purchase more glass and develop relationships with other donors.” As result of a growing number of donors, ongoing acquisitions, and the glass exhibition, the Museum of Art continues to increase its presence in the glass art community—locally, nationally, and internationally. The Art of the TeamMany American glass artists of the ’60s and ’70s were solo acts. One of the more important lessons they learned from the Venetians is how to work as synchronized teams to create larger and more complicated pieces that far exceeded the capabilities of a single person. “What Chihuly and others realized is that you need a team to make the kind of objects coming from American artists today,” says Nichols. “Once the process starts, anywhere from two to 17 people might be working on a piece. And each will have a special job. Someone might be blowing. Another person might be shaping. And another might be adding color.” While the team members carry out their specific tasks, the person who designs the piece might not be involved in the actual construction. Instead, he or she most likely directs the team, like a conductor of a symphony. Locally, the Pittsburgh Glass Center gives artists an opportunity to work in concert this way.

If You Build It, They Will Come

|

|||||

Time to Play · A New, More Personal Jesus · Mars Comes to Pittsburgh · Special Supplement: Thanks to Our Donors · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Anthony Rothbauer · About Town: Art Imitating Life · Field Trip: On the Road with Douglas Fogle · Science & Nature: Working the Bones · Artistic License: The Traveling Factory · First Person: A Traveler's Diary · Another Look: Sol LeWitt Drawings

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |