|

|

|

Bizarre Beasts

In a new exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, we come face-to-face with some of the strangest animals that ever lived and discover how their environments shaped their physical features—sometimes rather oddly.

By Julie Hannon

Move over, Sneetches. Even Dr. Seuss couldn’t dream this up.

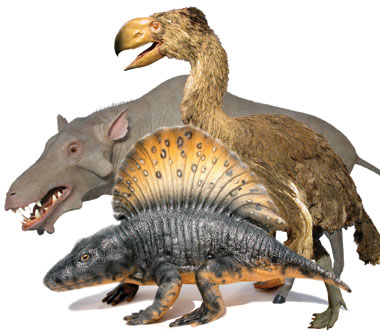

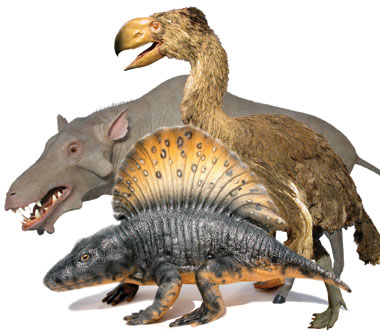

A head shaped like a boomerang. A bird that’s a cross between a giant chicken and a pony. The largest and most fearsome sea scorpion to ever have lived.

Some of Mother Nature’s craziest concoctions are part of Bizarre Beasts: Past and Present, on view through June 3 at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

At first guess, many of the outlandish creatures seem to be snatched from the pages of a sci-fi thriller. But each actually ran, swam, flew, or crawled on the Earth, some even before dinosaurs. “Some of these animals are so weird,” says exhibit creator Gary Staab from his studio in Golden, Colorado. “The ‘bizarre’ is the hook.”

But change is the overarching theme.

“These animals, both prehistoric and present, tell the story of how things are formed by the environment and how things change over time,” Staab says. “Looking back into time more than 300 million years can be so overwhelming—no one can conceive of those kinds of numbers. It’s so abstract. I wanted to make this exhibit fun and accessible from all levels to show the whole scale of life.”

Take bizarre birds, for instance. At the end of the Cretaceous Period, dinosaurs became extinct, leaving a vacancy at the top of the food chain. Some birds grew much larger to fill the void. Huge flightless birds like Diatryma (die-at-RYE-ma)—measuring some six feet tall—became the top predators, hunting ancestors of the modern horse such as Hyracotherium (high-RACK-oh-THEER-ee-um), comparable in size to a dog.

It took Staab more than a month just to glue the thousands of feathers onto the Diatryma model, his favorite in the exhibit. “Even though it’s this scary thing to look at, it has the grace of an ostrich in its running ability. Its form is so interesting

and beautiful.”

Visitors can also experience the first vertebrates and watch their transition from the water to land. The pterosaur (TER-o-SAWR), which lived 110 million years ago, is the star of the “radical reptiles” part of the exhibit. And what a star it is: this beast has an elongated jaw, three-inch teeth, and a 15-foot wingspan.

And if you think all this strangeness is just a thing of the past, a four-minute film reminds us about the diversity of life on Earth today. Think peacocks, jellyfish, opossum—even elephants.

“Giraffes, for instance, are absolutely nutty animals,” says Staab, a paleo-artist, sculptor, and illustrator, “but seeing them a million times changes our perspective.”

Already known for his life-size models of prehistoric animals on display in museums across the country—including future appearances of dinosaurs and other creatures in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s upcoming Dinosaurs in Their World exhibit—Staab started a wish list of interesting creatures for his own traveling exhibit. Four years later, after a lot of research, close consultation with scientific experts, and a lot of studio hours, Bizarre Beasts, the first exhibit Staab built from scratch, is on its third stop in a national tour slated to run through 2011.

A lot of the credit, Staab insists, belongs to his “go-to” guys—sons Max, 8, and Owen, 6. They’re responsible for testing the kid-friendly activities, including a computer interactive that encourages children to mix and match animal characteristics to see whether they would adapt to their environment. And by comparing a fish fin, a child’s arm, and a dolphin flipper—which all look different but share important similarities—we learn how they’re all related.

“They know on a gut level what works and what doesn’t,” says Staab of his in-house test marketers. “They are in many ways my target audience, and I bow to their wisdom. Getting a big ‘wow’ from a kid, you know you’ve done something right.”

Visitors to Bizarre Beasts can measure themselves against an eight-foot-long fossil cast of a Eurypterid, a sea scorpion that lived 410 million years ago, and discover why bumps, knobs, and tusks decorate many mammals.

On average, each model took Staab and up to eight collaborators about three or four months to construct. He starts by building an armature (structure) based on fossils and overlaying it with clay-sculpted muscles and skin. He then makes a cast of the whole object and might add material, such as silicone rubber, so it’s possible to punch hair or feathers into the surface of each model. He notes that many creatures with unique noses are hard to recreate because soft tissue doesn’t preserve as well as bones.

Sharks get headline-grabbing attention with their own display. The Helicoprion, a 13-foot whorl-tooth shark—what you might get when you cross a shark with a table saw—may be a novelty to visitors, but Staab is quick to point out that it flourished for tens of millions of years compared to today’s species, most of which prosper for only 3 million years.

“The whole idea behind Bizarre Beasts is to provide a bird’s-eye view of how everything changes, how it has in the past and will in the future,” says Staab. “Science needs to be fun and involve people in thinking about their world.”

- - - -

Don’t miss the Bizarre Beasts Public Celebration on March 3. Meet illustrator/sculptor Gary Staab and enjoy a docent-lead tour of Bizarre Beasts, special Discovery Room activities, family workshops, and Discover Carts. The celebration is free with museum admission.

|

Spring 2007

Spring 2007