For the Littlest Learners

By Kimberly

M. Riel

Young

children love playing and learning in Carnegie

Science Center’s Exploration Station,

Jr.

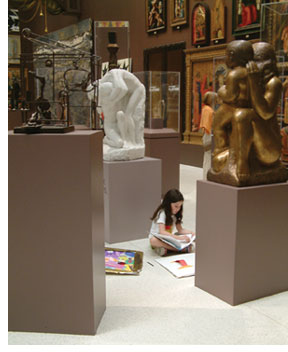

“I like her!” said

2-year-old Hannah to her mother as she sat down

beside Julie Williams, an educator from Carnegie

Museum of Art who was leading a play-date at

the museum one warm July morning. Together with

their parents, Hannah and five other toddlers

were in the sculpture garden at Carnegie Museum

of Art, hard at work and remarkably engaged.

They were making trees out of pieces of paper,

spongey material, feathers, pastels, and glue

following a brief discussion about a work of

art that they had seen earlier in the museum’s

entrance gallery. For 20 minutes, the entire

group was totally engrossed in their art-making.

When the play-date was over, each child proudly

shared his or her artwork with the group before

they all darted off to run and jump on the garden

steps.

As they giggled, screamed, and

chased each other, the children seemed to forget

everything

they

had just accomplished, but Julie was satisfied.

As a recent Carnegie Mellon University graduate

with a degree in psychology and a teaching

certificate from Chatham College, Julie knew

that she had

achieved her goals for the play-date: the kids

had fun, and the parents learned how they can

structure a future museum visit so their children

will enjoy it.

“

I think all the kids had a good time, and that’s

the whole idea,” says Williams. “A

child’s work is play, and when they play,

they learn. While they won’t remember anything

specific about the artwork we saw today, they’ll

remember the experience they had and they’ll

relate it to other things in their life. On a

very concrete level, they practiced some fine

motor skills, developed their social skills,

and challenged their emotional and language skills.

But I don’t think even their parents realized

that!”

How Children Learn

To a casual observer, the Museum of Art play-date

may have looked like organized chaos. However,

to an early childhood educator, it was a developmentally

appropriate activity. By piquing the children’s

curiosity about the subject of trees and then

allowing them to move around freely and make

their own trees at their own speed in a safe

and stimulating environment, Julie matched

the learning environment—the materials,

schedule, lesson, teaching methods, and physical

set-up—to the children’s developmental

level.

Psychologist Jean Piaget was the first

to study young children’s behavior and

develop the concept that children pass through

four stages

of development on their way to adulthood. The

children who participated in the Museum of Art’s

play-date ranged in age from 2 to 3 1/2 and fit

into Piaget’s sensorimotor (infant to age

2) and preoperational (ages 2 to 6) stages. Psychologist Jean Piaget was the first

to study young children’s behavior and

develop the concept that children pass through

four stages

of development on their way to adulthood. The

children who participated in the Museum of Art’s

play-date ranged in age from 2 to 3 1/2 and fit

into Piaget’s sensorimotor (infant to age

2) and preoperational (ages 2 to 6) stages.

“

Children in the preoperational stage learn by

exploring the world around them physically, through

activities that encourage them to manipulate

things, and mentally, by considering questions

or situations that cause them to wonder about

something,” says Melanie Dunn, a child

development specialist and professor at Duquesne

University and an educator at Carnegie Museum

of Art. “They’re also still sensorimotor

learners, which means they constantly want to

move around and smell, touch, taste, hear, and

see everything.

“

For children in these stages, the Museum of Art

has designed programs that encourage them to

explore, invent, and create their own theories

about the world by introducing them to a piece

of art and then letting them create their own

artwork based loosely on the piece we discuss,” adds

Dunn. “We always choose subjects that are

familiar to the children so they make an immediate

connection, and we make the visit very interactive

so they remember it.”

Comfortable Kids Make Lively Learners

“

We want people to know that the museums are excellent

places to bring young children to have fun and

to learn,” says Shirley Rust, program assistant

in the Discovery Room at Carnegie Museum of Natural

History. “Museums present children with

a unique learning environment—where else

can you see raw gems and real dinosaur fossils?

And while most of the exhibits in the museum

are for eyes only, there are a lot of things

that are very hands-on and perfect for young

children who are just learning to decode the

world by touching and questioning everything.”

While

the exhibits in the Museum of Natural History’s

Discovery Room are designed to stimulate curiosity

and imagination in people of all ages, they

are especially appealing to young children

because

the room is very home-like and everything is

within their reach. “The Discovery Room

is nice because it gives children another way

to learn about the things they see in the exhibits

upstairs,” says Rhonda Kelly, Discovery

Room program assistant. “But the best

thing about the Discovery Room is that it encourages

interaction between families and brings out

the

child in everyone.” While

the exhibits in the Museum of Natural History’s

Discovery Room are designed to stimulate curiosity

and imagination in people of all ages, they

are especially appealing to young children

because

the room is very home-like and everything is

within their reach. “The Discovery Room

is nice because it gives children another way

to learn about the things they see in the exhibits

upstairs,” says Rhonda Kelly, Discovery

Room program assistant. “But the best

thing about the Discovery Room is that it encourages

interaction between families and brings out

the

child in everyone.”

Providing stimulating

settings that foster parent-child and child-child

interaction and

allow for hands-on

activities is important to the education staff

at all four museums because children need to

feel comfortable in order to play freely and

learn effectively. At the Museum of Natural

History, the Discovery Room provides such a

setting, as

do the Discover Carts, which are staffed by

teen docents and located throughout the galleries.

Following the renovation of the Scaife Galleries,

the Museum of Art placed cozy couches throughout

the galleries where families can gather to

look at the artwork and read children’s

books about colors and images in art. And the

ARTventures

drop-in activity stations for families with

children make the galleries especially interactive

every

weekend. “Our weekly ARTventures projects

are designed to encourage both children and

adults to explore their reactions and responses

to a

work of art in the museum’s collection,” says

Marilyn Russell, Carnegie Museum of Art’s

curator of education. “The art-making

activity helps to stimulate conversation among

families

by sparking an exchange of ideas about the

piece. And since it takes place in the gallery

where

the work of art is located, not in an art center

someplace else, it helps to assure families

that a museum can be an interactive place where

you

can do a variety of things.”

At Carnegie

Science Center, exhibit areas created especially

for young children are marked with

tiny yellow handprints, and Exploration Station

Jr. is a 6-and-under-only zone designed to

encourage exploration and discovery through

hands-on activities.

It’s a parent’s and toddler’s

dream come true—with a Junior Lab, which

invites kids to explore different science careers;

a Construction Zone, which prompts kids to

sort and count materials while introducing

them to

the basics of physical science; a Ball Factory,

where kids are introduced to the concepts of

simple machines, colors, gravity, and teamwork;

a huge Water Zone; and a Quiet Spot where families

can talk about what they’ve explored,

read books or do puzzles together, and prepare

for

their next adventure.

At The Andy Warhol Museum,

families with children gravitate to the Silver

Cloud artwork where

they can play together with large floating

silver

pillows. Or they gather together in the Education

Studio, where every weekend—as part of

The Warhol’s Weekend Factory—The

Warhol staff offer art-making activities appropriate

for even the youngest child.

Learning Through

Play Learning Through

Play

With hands-on exhibits filling all five floors,

it’s easy for parents to recognize the

potential for fun and learning at Carnegie Science

Center, yet many think The Andy Warhol Museum

is inappropriate for young children. Think again.

“

As an artist, Andy Warhol played continuously,

and his art has a strong appeal to children,” says

Jessica Gogan, assistant director for education

and interpretation at The Warhol. “There

are vivid colors, enormous soup cans, and bright

yellow wallpaper printed with fluorescent pink

cows.

“

The Warhol offers a setting that is very open

to a child’s natural sense of play, and

it encourages adults to play as well,” adds

Gogan. “As adults, we recognize that play

is a vital part of a child’s development

and learning, yet play is every bit as important

to adults.

“

Play opens up the psychological space needed

for seeing new ideas, and it spurs imaginative

thinking,” says Gogan. “When we’re

playful, we’re relaxed and can think out

of the norm. Play is very important to the imagination

and problem-solving world of adults, and we often

don’t do enough of it.”

“

Playing together is the key,” notes Jessica

Stricker, director of educational experiences

at Carnegie Science Center. “When parents

or grandparents and children play together, the

whole world opens up.

“

Teachable moments pop up everywhere. Sometimes

it’s the child who is learning; sometimes

it’s the parent or grandparent who learns

something new; and sometimes they’re all

learning together. No matter what the scenario,

it’s fun for everyone, and that’s

the ultimate goal—to enjoy being, and learning,

together.”

Back to Contents

|