What

a different city Pittsburgh would be if Andrew

Carnegie hadn’t lived here. Without his

business acumen, his love of art, science, literature,

and music, and his belief in education, we wouldn’t

have our libraries, Carnegie-Mellon University,

or a stately home for dinosaurs and Degas. And

without his desire to create an art collection

filled with “the old masters of tomorrow,”

we wouldn’t have the Carnegie International,

the prestigious survey of modern art that draws

the world’s attention to Pittsburgh every

few years.

Trying to quantify the International’s

importance to Carnegie Museum of Art, the city

of Pittsburgh, or the art world in general is

just about impossible. But former curators,

informed art lovers, and others have much to

say about the ever-evolving exhibit, widely

regarded among modern art cognoscenti as second

in stature only to the Venice Biennale or Germany’s

Documenta, both of which are curated and presented

very differently than the International.

Former Carnegie Museum of Art

Director John Lane, who oversaw the 1982 International

and co-curated 1985’s version with the

late John Caldwell, calls it Carnegie Museums’

single most significant contribution to culture

in general. “The Carnegie International

is Pittsburgh’s great cultural legacy,”

says Lane, who left Carnegie Museum of Art to

head the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

and is now director of the Dallas Museum of

Art. “It’s the one event in any

of the arts that occurs in Pittsburgh that the

whole world—at least, the visual arts

world—pays serious attention to.”

Madeleine Grynsztejn, who organized

the 1999 International as the Museum

of Art’s curator of contemporary art,

concurs. Both nationally and Internationally,

she says, “It’s one of the most

important indicators of our culture.

“The Carnegie International

is always looked on as a kind of prescient compilation

of the best art made anywhere,” says Grynsztejn,

now senior curator of painting and sculpture

at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “It’s

used almost like a resource for the growth of

collections and exhibitions elsewhere. If you

made a study of the artists in the current International

since they’ve been asked to be a part

of the International, I guarantee their exhibition

activity has increased.”

Lane says similar artistic surveys

have come and gone, but the Carnegie International’s

more than 100-year history shows both stability

and commitment. Only one year younger than the

Venice Biennale, it’s also got the venerability

of age. “You know it will always be there

and always be important,” he says. “The

Carnegie International is not ephemeral.”

An endowment of its own, begun

in 1980—unusual for specific exhibitions—further

assures the International’s future.

“The

Old Masters of Tomorrow”

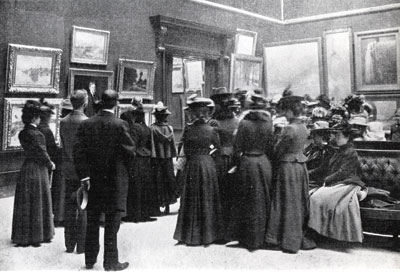

When art aficionados discuss Andrew Carnegie,

they often use the word “visionary.”

Lane calls Carnegie’s foresight atypical

for the development of an art museum. Carnegie

saw the International not only as a means of

presenting current artistic achievements to

Pittsburgh audiences—as the salons were

doing in Europe—but also as a way to bring

significant contemporary art to Pittsburgh for

possible addition to the Museum of Art’s

permanent collection.

“It was really a very insightful strategy

that Mr. Carnegie developed,” says Lane,

“and he was not an art collector. I don’t

even know that he was serious about art, not

personally, but he was serious about providing

opportunities and he was serious about developing

cultural institutions for the city of Pittsburgh.”

Former Carnegie International Co-Curator Lynne

Cooke, who, with Mark Francis, organized the

1991 International, thoroughly researched both

its history and that of its founder, and studied

“the philosophy of the whole institution.”

“Carnegie didn’t want a ‘collection’—he

wanted it to be vital and ever-changing, with

an emphasis on vanguard art, on bringing things

to Pittsburgh in a way that would be exciting

for audiences,” she says. “When

you look at the permanent collection of 20th-century

art, you can feel how the Internationals have

actually shaped Carnegie Museum of Art’s

collection, shaped the institution.”

Lane says Carnegie also wanted to differentiate

his institution from the growing art collections

of other wealthy American businessmen, including

his one-time partner, Henry Clay Frick. Most

of those men were buying European old masters.

Carnegie declared his museum would house a collection

of “the old masters of tomorrow.”

According to Sam Berkovitz, owner of Concept

Art Gallery in Regent Square, Pittsburgh, “The

International is central to the Museum of Art’s

identity. To me, it’s a wonderful opportunity

to see what’s current and what’s

important in contemporary art. I feel like I’m

cheating because it saves me countless months

of travel.”

Tom Sokolowski, director of The Andy Warhol

Museum, says the Carnegie International is really

beneficial to smaller museums for the same reason.

Many of them just don’t have the travel

budgets to traverse the world in search of art.

“This may not be as good as seeing what’s

going on Tokyo,” he says, “but if

you see a half-dozen good Japanese artists,

at least it’s emblematic of what’s

going on in Tokyo.”

Neutral

Ground

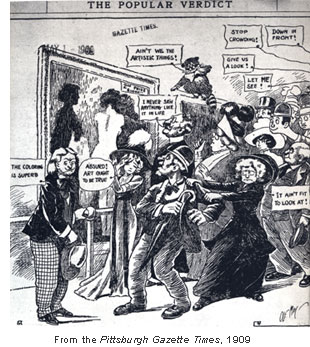

Unlike Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Arts

Festival, which seems to have a controversy-arousing

piece of art nearly every year, the International,

according to Lane, historically has not been

“flavored” by scandal—not

even in the 1999-2000 exhibition, when the International

showcased works by British artist Chris Ofili.

Ofili’s work, which incorporates purified,

dried elephant dung, incensed then-New York

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani when Ofili’s The

Holy Virgin Mary was displayed at the Brooklyn

Museum of Art earlier in 1999.

“I don’t think the exhibitions

that were presented early on, when Carnegie

was still alive, were in fact cutting edge,”

Lane says. “I think they were very solid,

but I think they were essentially conservative.” “I don’t think the exhibitions

that were presented early on, when Carnegie

was still alive, were in fact cutting edge,”

Lane says. “I think they were very solid,

but I think they were essentially conservative.”

A history of the International, titled International

Encounters: The Carnegie International and Contemporary

Art, 1896-1996, suggests that there were some

early “scandals” regarding presentations

of nudity, but on the whole it confirms Lane’s

assessment. Not until the 1950s and early ’60s

did the Internationals get involved with what

Lane terms “advanced visual arts,”

i.e., abstraction.

By all accounts, the International slipped

in quality and importance in the ’70s

and early ’80s, but since 1985, says Lane

with a laugh, “It has been an exhibition

about the leading edge, although perhaps not

the bleeding edge.

“One of the particular virtues of having

this show in Pittsburgh is that it isn’t

a city that’s a lightning rod for cultural

controversy,” he adds. “A lot of

artists have historically enjoyed the invitation

to show in Pittsburgh because it’s neutral

ground. It isn’t like showing in one of

the great art capitals of the western world.

The environment is different. It’s not

under the radar, because people are certainly

cognizant of what happens there. It’s

just that it’s not a blood sport in Pittsburgh.”

He notes Pittsburghers tend to be open-minded

about art, a trait they may have cultivated

over a century of Internationals. Instead of

dismissing new, different, strange—and

perhaps disturbing—work, they’re

interested in learning first, then forming an

opinion. The Andy Warhol Museum’s well-attended

exhibitions, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography

in America, and new Inconvenient Evidence: Iraqi

Prison Photographs from Abu Ghraib, reinforce

that theory.

Grynsztejn says the International’s success

hinges on compelling, accessible material, but

also on an audience “that is interested

and curious and intelligent, not necessarily

expert and empathetic.”

Western Pennsylvanians have always turned out

for Internationals, whether they really “know”

art or not. That’s a testament to the

community’s appreciation for what Lane

calls “this cultural endeavor and the

pleasures and provocations that one experiences

when coming to see it.”

Kilolo Luckett, a University of Pittsburgh

graduate in art history who does “know”

art, describes the International’s impact

on the regional art community as multi-layered.

Besides the opportunities it provides for art

institutions, galleries, and individual artists

to interact, she says, “The International

brings fresh, cutting-edge, contemporary work

that engages me on a visceral and intellectual

level. It creates a ‘hyper’ synergy

and awareness that pulsates and enlivens the

city.”

Luckett was a curatorial assistant at the Wood

Street Galleries and a publicist at Pittsburgh

Filmmakers before joining Cool Space Locator,

a non-profit real estate company. She loved

the fact that the 1991 International involved

other locations, including the Mattress Factory

on the North Side, which was the site of four

installations, and the fact that she could interact

with the artists and art critics at various

International-related events.

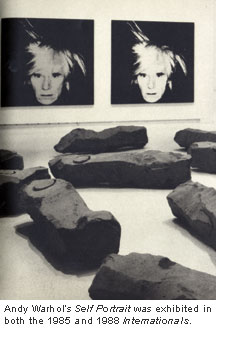

One North Side institution—The Andy Warhol

Museum—might not be in Pittsburgh if not

for the International, Lane suggests. He theorizes

that the ’85 and ’88 Internationals

proved Pittsburgh’s devotion to showing

“the greatest works of our time”

—including, in ’88, a series of

Warhol’s self portraits. One North Side institution—The Andy Warhol

Museum—might not be in Pittsburgh if not

for the International, Lane suggests. He theorizes

that the ’85 and ’88 Internationals

proved Pittsburgh’s devotion to showing

“the greatest works of our time”

—including, in ’88, a series of

Warhol’s self portraits.

Warhol studied art at Carnegie Museum of Art,

he exhibited there, he was born in Pittsburgh.

All these were factors in considering whether

The Warhol would wind up in Pittsburgh. But

Lane says the International proved to the Warhol

Foundation and the Dia Center for the Arts,

both of whom would decide where the museum would

be located, that Carnegie Museum of Art was

a peer institution and that the city took contemporary

art seriously.

“It would be my sense that one of the

legacies of Andrew Carnegie’s invention

of this exhibition and the institution’s

perpetuation of it over a century is that it

made Pittsburgh a serious candidate for having

this incredibly great, incredibly important

one-person museum,” says Lane.

A

Major Attraction

When discussing the International’s effect

on Pittsburgh and its people, the tourism factor

must be considered as well. The International

does bring its share of visitors to the area.

Tinsy Lipchak, director of tourism and cultural

heritage at the Greater Pittsburgh Convention

& Visitors Bureau, says, “People who

are in the know about contemporary art come

here specifically to see the International.

It does have its place in the scene, and not

just for high art/contemporary art aficionados,

but for the average tourist who wants to see

something cutting-edge.”

Those who visit for the first time are inevitably

surprised by how many other attractions the

city has to offer, she says. The hard-core International

art community shows up to party —and to

shop — during the opening weekend.

Says Grynsztejn, “The opening is not

only very good-looking and filled with the latest

fashions, it’s also filled with artistic

bounty hunters. Every collector, every museum

director, and every curator worth his or her

salt is going to that opening on the lookout

for things they can acquire because 2004 International

Curator Laura Hoptman will have done this incredible

groundwork on their behalf.”

Grynsztejn can’t say enough about the

experience of overseeing an International.

“The International hones you, it hones

your curatorial skills like very little else

can,” she says. “Carnegie Museum

of Art has acted as a sort of Harvard of the

curatorial world. One of the things that I don’t

think it’s touted for enough is that it

trains the curatorial field and produces the

best curatorial minds, who then go out and influence

institutions nationwide.”

Each International opening is also an alumni

gathering of sorts for former curators. “I

look forward to it every time,” Grynsztejn

says. “I look forward to it as a way of

learning even now. It’s the best show

in the country.

“Andrew Carnegie did the right thing.”

Back to Contents |