The Politics of Art

Artists

tackle life’s biggest issues with their

work.

By Vicky A. Clark

The art of our times changes before

our very eyes with sudden shifts and unexpected

turns that confuse and unnerve us. Combine that

thrill and challenge with world-wide twists

and turns, and we are left with a feeling of

vertigo in both our personal and public lives.

How can we make sense of the world in which

we live? Can art help us to process and understand

change?

Laura Hoptman’s fresh, multi-faceted

look at the art of our times raises this possibility.

In her catalogue essay, she quotes philosopher

Theodor Adorno: “‘In order for a

work of art to be purely and fully a work of

art, it must be more than a work of art…’”

explaining that “art [is] capable of bearing

the burden of exploring territories traversed

by philosophy, religion, political ideology,

and science” and that “artists in

the show have [chosen] art as a meaningful vehicle

through which to confront fundamentally human

questions: the nature of life and death, the

existence of God, the anatomy of belief.”

Hoptman

suggests that art can play an important role

in our lives. Artists can raise issues and suggest

different solutions, roles usually reserved

for those in other disciplines such as leaders

in politics, religion, science, and philosophy.

Artists’ creativity and imagination—often

ignored or seen as marginal fluff in an age

ruled by rationalism, logic, and empiricism—add

another voice to these discussions. Hoptman

suggests that art can play an important role

in our lives. Artists can raise issues and suggest

different solutions, roles usually reserved

for those in other disciplines such as leaders

in politics, religion, science, and philosophy.

Artists’ creativity and imagination—often

ignored or seen as marginal fluff in an age

ruled by rationalism, logic, and empiricism—add

another voice to these discussions.

However, it is difficult to measure

if including art in our larger discourse has

an impact. In fact, there is no proof that any

work of art actually changed history or the

way we think. Even Picasso’s Guernica—usually

considered the most political work of art—did

not end the Spanish Civil War. From the very

beginning, however, there have been high hopes

for art—whether by hunters looking forward

to a successful hunt, Egyptian pharaohs and

Roman emperors populating their lands with their

own image to assert their power and control,

or Christians carving Bible stories onto medieval

cathedrals to spread the word of their religion.

Much later, the Nazis, who advocated social

realism, organized the Exhibition of Degenerate

Art to distinguish between proper and immoral

art.

Throughout the history of the

International, we can see how hopes have been

raised periodically for art’s efficacy

in a larger context. At the very beginning,

Andrew Carnegie—like other philanthropists

in the Gilded Age—believed that his palace

of culture would improve the quality of life

of Pittsburghers, bringing them “sweetness

and light” through the civilizing and

educational power of art. After experiencing

the visualization of manifest destiny in the

White City of Chicago’s World’s

Fair in 1893, where 21.5 million paid to see

some 65,000 exhibits documenting success and

innovation, Carnegie wanted Pittsburgh to play

a similar role. At a time when the American

character was being defined and the country

was entering into world politics as a strong

contender, he suggested that American art belonged

with European art as an example of the triumph

of American ingenuity and culture.

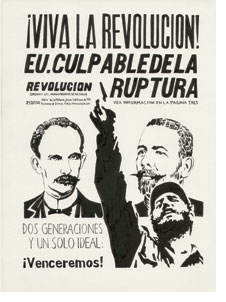

Many

artists took a political stance during the world

wars and the intervening Depression, from the

pointed criticism in Picasso and the German

Expressionists to the alternative world in Surrealism

and the rebellious actions of the Dadaists.

Rarely did such politics cause a stir at the

International, though, Franklin Watkins’

Suicide in Costume, which won the top

prize in 1931, was troublesome. He equated his

robust, dead clown prone on a table with a gun

with “our civilization” during the

deep Depression. Unlike usual aesthetic debates,

this work engendered uproar about the proper

subject and role of art. The public outcry was

addressed in a local article It’s Ugly

But Is It Art? International Curator

Homer St. Gaudens later claimed that the exhibition

was “the laboratory wherein was touched

off the fuse that exploded the charge that within

the last two decades blew up the illusions of

self-contented ignorance.” Many

artists took a political stance during the world

wars and the intervening Depression, from the

pointed criticism in Picasso and the German

Expressionists to the alternative world in Surrealism

and the rebellious actions of the Dadaists.

Rarely did such politics cause a stir at the

International, though, Franklin Watkins’

Suicide in Costume, which won the top

prize in 1931, was troublesome. He equated his

robust, dead clown prone on a table with a gun

with “our civilization” during the

deep Depression. Unlike usual aesthetic debates,

this work engendered uproar about the proper

subject and role of art. The public outcry was

addressed in a local article It’s Ugly

But Is It Art? International Curator

Homer St. Gaudens later claimed that the exhibition

was “the laboratory wherein was touched

off the fuse that exploded the charge that within

the last two decades blew up the illusions of

self-contented ignorance.”

In

1988, the International preceded the

end of the millennium debate. Joseph Beuys’

End of the Twentieth Century anchored

a somber show where artists addressed AIDS,

consumerism, gender, and politics. Julian Schnabel

used St. Sebastian as a symbol for AIDS, Anselm

Kiefer referenced the Holocaust, and Elizabeth

Murray used the kitchen table to address gender

issues. These issues were part of the next several

Internationals, though politics was

never the core of any exhibition. In

1988, the International preceded the

end of the millennium debate. Joseph Beuys’

End of the Twentieth Century anchored

a somber show where artists addressed AIDS,

consumerism, gender, and politics. Julian Schnabel

used St. Sebastian as a symbol for AIDS, Anselm

Kiefer referenced the Holocaust, and Elizabeth

Murray used the kitchen table to address gender

issues. These issues were part of the next several

Internationals, though politics was

never the core of any exhibition.

In each of these cases, the hopes

for works of art outpaced the expectations of

the viewers and curators and even the artists

themselves. Rarely is politics the raison d’etre

of a work, and rarely are politics completely

absent. Even pure abstraction can have political

overtones.

We

cannot measure the effect of art upon those

that see it, nor can we prove that the claims

and hopes attached to art in the last 106 years

were realized. However, this year’s International

signals a shift. The art here, too, bears the

burden of expectations. Many of the artists

have chosen the commonplace as their subject

while contributing to the larger discussions

of the meaning of life, adding different points

of view. Perhaps the arts will regain their

place in the make-up of the Renaissance man

and begin to move away from the over-specialization

and isolation of contemporary knowledge and

research. At the very least, they are storming

the gates, demanding to be relevant, contributing

new perspectives, and giving new hopes to their

creators. n We

cannot measure the effect of art upon those

that see it, nor can we prove that the claims

and hopes attached to art in the last 106 years

were realized. However, this year’s International

signals a shift. The art here, too, bears the

burden of expectations. Many of the artists

have chosen the commonplace as their subject

while contributing to the larger discussions

of the meaning of life, adding different points

of view. Perhaps the arts will regain their

place in the make-up of the Renaissance man

and begin to move away from the over-specialization

and isolation of contemporary knowledge and

research. At the very least, they are storming

the gates, demanding to be relevant, contributing

new perspectives, and giving new hopes to their

creators. n

About the author

Vicky A. Clark held a

number of positions at Carnegie Museum of Art

from 1981 to 1996. Her last project was the

book International Encounters: The Carnegie International and Contemporary Art, 1896–1996.

After six years as curator at the Pittsburgh

Center for the Arts, she is now an independent

curator working on exhibitions across the country

and a professor at various local universities.

Back to Contents |