By Gina Frey

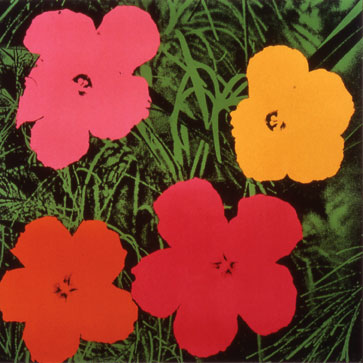

Andy

Warhol, Flowers,1964, ©AWF

For as long as painters have applied

pigment to canvas, or artisans have perfected their

craft, the flower—in all its symbolism, fragility,

and mysterious allure—has been the perfect

subject.

For John Smith, assistant director

of collections and research at The Andy Warhol

Museum,

the flower

motif is a “great cultural touchstone” and

an ideal framework through which to examine Andy

Warhol’s voluminous body of artwork. Smith

is the curator of, Flowers Observed, Flowers Transformed,

the kick-off exhibition of The Warhol’s yearlong

10th anniversary celebration. The exhibition, which

opens May 16, uses Warhol’s many flower-themed

works as the foundation for a broader examination

of the flower in art.

“

On the occasion of the Museum’s 10th

anniversary, we wanted to start looking at

Warhol’s work

thematically, rather than chronologically,” says

Smith. “The subject of flowers gives

us the perfect first opportunity to play with

this new

way of looking at the collection.”

In

order to illustrate where Warhol’s works

fall within the rich history of floral art,

Smith has gathered more than 150 paintings,

photographs,

decorative pieces, textiles, botanical prints,

glass works, and contemporary sculptures from

artists as diverse as the 17th-century Dutch

painter Ernst

Stuven, Eduoard Manet, Claude Monet, Robert

Mapplethorpe, contemporary British artist Anya

Gallacio, and

contemporary American artist Jim Hodges. Spanning

more than six centuries of floral artwork,

the exhibition examines the beauty, symbolism,

and

scientific significance of flowers by looking

at how Warhol and others have interpreted them.

Warhol’s

Floral Works

Warhol turned to the flower for inspiration time

and again. In the 1950s, he made drawings of flowers

in the tradition of representational still life.

Blotted-line daisies, roses, and gold-foiled irises

appeared in early commissioned artworks and book

illustrations. He returned to the floral still

life in 1974, with a series of screen prints based

on Japanese ikebana arrangements.

It was in 1964,

however, that Warhol embarked on one of his most

successful projects using the flower

motif. In a series of paintings based on a photograph

of hibiscus blossoms, Warhol drenched the flowers’ floppy

shape with vibrant color and set them against a

background of rich undergrowth, transforming them

into psychedelic indoor décor. Smith sees

similarities between these 1964 Flowers and Japanese

prints, as well as Claude Monet’s famous

Water Lilies. In fact, art critic David Bourdon

noted in a Village Voice article in 1964 that the

flowers appear to float right off the canvas, “like

cut-out gouaches by Matisse set adrift on Monet’s

lily pond.”

“Flowers in art and culture have been ubiquitous

since the beginning of recorded art history,” says

Smith. “The floral theme wasn’t any

more exhausted when Warhol was doing it than when

17th-century Dutch painters or the Impressionists

were. But Warhol was sly; he was always playing

with traditional art historical themes.”

A Source and Symbol of Life

The value of an exhibition as extensive and wide-ranging

as Flowers Observed, Flowers Transformed is in

how its breadth illuminates the symbolic role

the flower has come to play in art and culture.

It was in the Renaissance period that the flower

escaped the clutches of its long-held religious

symbolism and came into its own as a subject

worthy of pictorial representation in the Western

world—as a symbol of the natural cycle

of life.

During this era, flowers took center

stage in vanitas paintings, which were perfected

by Dutch artists

in the 16th- and 17th-centuries and are represented

in this exhibition by works by Caspar Peter van

Verbruggen, Jan van Os, Ernst Stuven, and others.

These still-life paintings depict lush bouquets

of exotic flowers in full bloom, cut and arranged

in ornate vases. Commiss-ioned by the wealthy

and the royal, these paintings adorned sitting

parlors

and complimented exquisitely upholstered furniture.

The paintings appear to celebrate the wealth of

the patron, but close readings reveal that

they

also had symbolic meaning. Artists often used

the paintings to send messages to their wealthy

clients

about the fragile nature

of their earthly possessions, the dangers of

arrogance and pride, and the inevitability

of their death.

In one painting in the exhibition, flowers

bearing dewdrops draw attention to their comparatively

short lifespan and insects feed upon the arrangement’s

succulent leaves. In another, tiny blossoms show

signs of wilting and decay. In a time when smallpox

and countless other

diseases plagued Europeans, these paintings

served as subtle reminders of

the brevity of life.

Other artists in Flowers Observed, Flowers Transformedhave approached

the notion of the

flower as a

symbol of life rather overtly.

One of the

most delicate and quietly beautiful contemporary

pieces in the exhibition is

a sculpture by Yoshihiro Suda. A young

artist from Japan,

Yoshihiro carves fragile, hyper-realistic,

life-size, wood

sculptures of common weeds and flowers

like camellias, roses, and magnolias. His work

is

represented

in this exhibition by a 1998 sculpture

entitled, Tulip.

In the piece, the yellow petals of a solitary

tulip fall away from their stem and tumble

down the gallery

wall as if guided by a swirling breeze.

Installed within an otherwise empty gallery, the

work

demands silent introspection on the ephemeral

quality

of life.

Anya Gallaccio also deals with

the temporal quality of flowers. Her piece, preserve

beauty, includes

800 live red gerbera daisies pressed

between sheets of glass. Throughout the course

of the exhibition,

the flowers will begin to brown and wither

beneath the glass, creating a kind of

natural performance

art that speaks volumes. Tokens and Tributes

While flowers have symbolized both life and death,

they are also widely used to commemorate it.

Funereal flowers speak volumes when words can’t

be found and function as a universally accepted

and appreciated form of memorial. Smith and the

curatorial staff at the museum believe Warhol’s

1964 Flowers paintings may have been created

as a kind of tribute to the slain President John

F. Kennedy. Warhol created the works along with

his portraits of the grieving Jacqueline Kennedy

only months after the assassination.

The contemporary

artist Tom Burr has used Warhol’s

1964 Flowers series as inspiration for his own

floral tribute. His 2003 work, Clumped, depicts

two black vinyl flowers in the shape of Warhol’s

famous series set against a black backdrop. In

addition to being a dark reference to Warhol’s

work, Burr created the piece as a commemoration

of the heyday of 1970s gay underground culture.

The

themes and symbolism to be found in Flowers Observed, Flowers Transformed are as

varied as

the works themselves, and interpretive explorations

of these themes—such as the sensual and

poetic associations and uses of flowers through

the ages

or the scientific and medicinal properties

of specific flowers—will be interwoven

with the display of artwork.

Says Smith: “I

hope the wide variety of work in the exhibition

not only will highlight the nearly

inexhaustible creativity with which artists

have approached this subject, but also

will remind visitors

of the powerfully resonant role flowers continue

to play

in our culture.”

Back to Contents

|