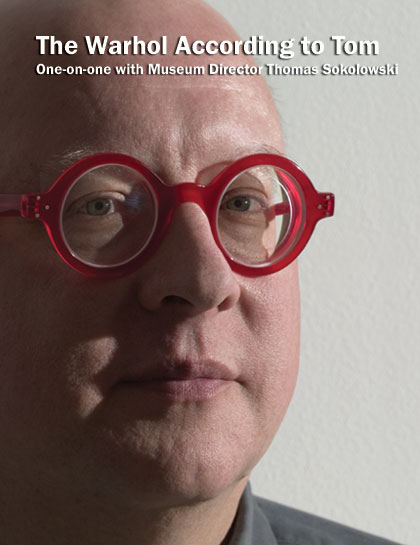

By Kimberly M.

Riel

Who was the key figure in bringing

Warhol’s collection to Pittsburgh?

I don’t think there was any one key figure,

and I don’t think the collection came to Pittsburgh

just because it was Warhol’s hometown. I do

think it was a strategic moment when all things came

together.

It was the fact that Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

had a system that could much more easily absorb a

new entity, and that Senator Heinz, who was a visionary,

really wanted it here. He felt somebody with an international

reputation would help raise the stakes of the depleted

steel city of the past.

The sub rosa catalyst may have been that there was

a very famous collection of abstract expressionist

pictures by G. David Thompson that came to Pittsburgh,

and people didn’t take to him. Those pictures

are now in major museums throughout the world, and

I think that some of the more discerning natives

decided that they couldn’t make the same mistake

twice.

Which of Warhol’s values do you think

The Andy Warhol Museum has been able to keep alive?

Warhol was totally entrepreneurial, exploited the

media, and created art of every sort. We do the same.

The idea of democratizing the art-viewing experience

is Warhol’s, and so is the idea of hanging

pictures differently. Warhol once made the comment

that “museums should be more like department

stores,” and we’ve taken that approach—offering

more in-depth experiences juxtaposed with fast thrills!

What do you think Warhol would have thought about

the museum?

Warhol wouldn’t have liked that the museum

is in Pittsburgh. He would have wanted it to be a

penthouse at the Met, because then it could be the

biggest and the best right there on Fifth Avenue.

However, the idea of a working-class kid who reached

high was very much a part of his cast and I think

there are some things he would have liked about the

place. He would have loved our website (but he would

have done a more brilliant one because he was Andy

Warhol). I think he would have liked

some of the easy, more commercial things we’ve

done. And in a funny kind of way, even though he

wasn’t overtly political, he would have liked

the idea of using art as a fulcrum to leverage

change in society—that was what he was all

about.

Do you think The Warhol has evolved the way its

founders thought it would, or is this evolution largely

your vision?

I don’t think anybody was necessarily thinking

about how the museum would evolve when it first opened.

I think they just wanted a Warhol Museum—kerplunk!

However, even before my time, the museum realized

there wasn’t going to be enough to engage our

local audiences, to make our earned income goals,

etc. I think what I may have contributed to The Warhol’s

evolution is the notion of the “Museum-Plus”—looking

at museums in a less grand but more modern and directed

way.

Do you think the audience in Pittsburgh is a good

audience for The Warhol?

I think it is. When we did our strategic plan, one

of the things we recognized is that we were this

specific museum in this specific city. The museum

would work on a whole different level if it were

in a different city. If we were in New York we would

probably have 750,000 visitors a year without doing

anything, simply because of tourism, Warhol’s

fame, and the art-going public. We’re never

going to get that here.

If The Warhol were just about

getting the most people in the world to see Warhol’s

work, we shouldn’t

be here. But seeing Andy Warhol’s works in

the notion of a city that has transformed itself,

just as Warhol did, is very interesting.

If you

look at everything Warhol did, it was all about

transformation. It was about making Campbell’s

soup into art, about making going out at night

to Studio 54 an artwork. And I think that was

from someone

who came from working class roots in a working

class city.

I hope and expect that we’re

playing the same role that Warhol played on a

wider scale back in

the 1960s. We’ve been transformative in

the way that we deal with TV, and government,

and products,

and social issues, and communities. I think that’s

where museums of all sorts should be going.

Do you find the word “museum” restricting?

Jessica Gogan, our assistant director for education,

told me, “Tom, you’re right and you’re

wrong . . . museums can be vital and exciting—it’s

just that most museums are not. We don’t

need to change the word, but redefine what it means.”

I

think of museums as places where the Muses reside,

not places where you just hang up their old tutus

and worry if the lace is going stale. But I don’t

think that’s the way that a lot of museums

around the world view themselves. People largely

look at museums today in 19th-century Germanic

terms.

I think we really break the boundaries that

way, unabashedly. At The Warhol we’re willing

to do something like Without Sanctuary or the

Kennedy exhibition, both of which are about American

and

world culture, which is now very much at the

heart of what art making is all about.

We also

see our Good Fridays programs and

the political things we do as our meat and

potatoes,

but many

people would say all we do is throw parties.

The difference

is that while we might have a party and use

it to make money, at the same time, we’re

doing the stuff that’s really important

to us. We just don’t do it in the same

old, boring, 19th-century way.

For example,

if you say you’re going to do

a wonderful exhibition on Etruscan Funerary

urns and then give a party with whores wearing

pasties

where everyone dances the Mambo, that’s

cheesy, and it’s not what we do. But

if you say, sex played a seminal role in the

way the Etruscans dealt

with their culture that was very different

from what the Greeks and Romans did, and you

integrate that

message in an archaeologically sound way into

the exhibition, then you’re really getting

a holistic look at the culture. That’s

what we do that’s

different.

Why was it important for you to build a culture

around The Warhol?

I think it was important because, quite frankly,

we needed more people to come and see the museum.

If you’re selling steroids at the Olympics

it’s a no-brainer. But if you’re selling

steroids at a conference of philosophers, they better

appeal to brain cells as well as to muscles.

It’s 2004 and Warhol died 17 years

ago. Is his work getting to be old-fashioned at

this point?

Not in the least. Because Warhol really understood

how people thought, the role the media played in

those thoughts, and had such a sense of style, his

work is still very easy to absorb.

His early years

were all about Pop to be sure, but when you get

into the car crashes and the electric

chair paintings, it was a whole different sensibility.

Many of the Pop artists of the day—Jasper Johns

and Lichtenstein—had a fun-fun-fun mentality.

Warhol took a more sober, investigatory approach

into everyday things that still appeals to audiences

today.

What do you like most about your role?

I work with a smart, young staff that isn’t

afraid of change. I love the chance to be able to

spin on a dime; and I love to engage people who have

never come here before.I would love to crack the

religious community and show that we can engage

in religion in a serious

way, and still get away from the boring stereotypes.

I

also enjoy interfacing with the city. I’m

proud of the fact that one of the trustees said

to me that I was probably one of the most visible

people

in the city who was not a politician or a sports

figure. That’s important—not because

it’s about Tom Sokolowski—but because

it means an arts leader is thought of as being

worthy to comment on issues such as the failure

of the school

system for example.

What are The Warhol’s plans for the

next 10 years?

We’ve done surveys and the analysis tells us

we’re doing some things well. I would like

us to set up a curriculum for educators to instruct

them how to teach art using Warhol as a model—but

not the only model. We’re interested in selling

the curriculum—philosophically and educationally—because

the school systems aren’t doing it well. It’s

about extending the museum outwards, and also about

bringing people into the museum to do things in a

different way.

We would like to turn the museum into

a complete media-savvy center. Maybe we should

merge with Filmmakers?

I would also like to open a for-profit arm of the

museum where we could design and market our products,

whether literary or decorative. And, I’ll

leave you with the idea that perhaps we should

merge with Target. Andy really would have thought

that

was a great idea! Is there any message about The Warhol that you want

people to think about on this important 10th anniversary?

Keep on watching. You never know what we’ll

do next.

Back to Contents

|