The Warhol’s preview

party for its 2000 exhibition Possession Obsession

pushed some envelopes and was

ranked by many as one of the year’s best events.

Photo courtesy of the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review

By Lynne Margolis

Andy Warhol left

Pittsburgh as soon as he graduated from college and

never looked back. So when word spread

about the city’s campaign to bring him home—so

to speak—via a new museum, it was natural for

cynics and skeptics to ask, “What for?” It

was a legitimate question. And so was the answer. “Why

not?”

Why shouldn’t Pittsburgh try to identify

itself with one of the most important cultural

figures in the 20th century? Why shouldn’t

Pittsburghers get a tourist attraction that

would put the city on the map for reasons other

than steel and sports, and feed its economy

as well? Local leaders would have been crazy

not to grab an opportunity to embrace and celebrate

Warhol’s link to Pittsburgh, and, if

possible, give this conservative town a much-needed

dose of hipness.

Today, The Andy Warhol Museum

has won many converts. Some naysayers changed

their tunes

after friends, relatives, or business associates

pressed them into service as museum tour guides.

Even those who have never roamed among the

museum’s seven concrete-poured stories

seem to appreciate its importance. They actually

brag about it to outsiders when listing what

makes Pittsburgh—to borrow an old marketing

phrase—someplace special. In fact, now

it’s hard to find a high-profile

local resident who has anything negative to

say about the museum. But Chris Potter, managing

editor of the weekly Pittsburgh City Paper,

admits he was one of those early doubters. “I

was writing about art in those days and I tended

to think that Warhol actually was a sort of

pernicious influence on art. An undeniable

influence, but a pernicious one,” he

recalls. “It’s obvious that he

felt he was better off without the city and,

to a large extent, the city returned the sentiment.”

Potter

says he feared the new institution would be

the museum equivalent of Warhol’s

art: an ironic monument to consumerism and

as superficial as the artist himself had sometimes

described his work. Now, Potter says, “I’m

very glad the museum is here. The staff does

a better job of being Warhol than Warhol did.”

Broadening Minds, Attracting Business

Like Potter, Pittsburgh City Councilman Bill

Peduto also has a responsibility to look

at the city’s assets and shortcomings

with a clear eye. As far as he’s concerned,

there’s no question about the museum’s

status as one of the city’s most important

institutions.

“

To me, The Warhol is the equivalent of the

Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam,” he says. “In

the minds of people in the U.S. and throughout

the world, Pittsburgh has become a destination

for art.”

No one has to tell that to Tinsy

Lipchak, director of tourism and cultural heritage

at the Greater

Pittsburgh Convention & Visitors Bureau,

who says visitors leave Pittsburgh with a completely

different attitude than they had when they

arrived. “The Warhol helps change people’s

perceptions of Pittsburgh as a dirty, smoky

city,” she says. “It tells people

that there is a contemporary art scene here.”

Both

Lipchak and Peduto have observed growth in

the number of artists choosing to stay in

Pittsburgh, and they attribute that partly

to the museum’s

presence. Says Peduto: “The Warhol offers

a sense of hope for those young artists who

know there is such a thing as urban chic in

a town like Pittsburgh. It really gives them

a sense of pride and identity like other people

find with the Steelers.”

|

|

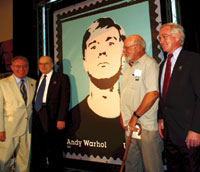

| Andy Warhol

Foundation President Joel Wachs, John and

Paul Warhola, and Pittsburgh Mayor Tom

Murphy preside over the Andy Warhol commemorative

postage stamp in 2002. |

The Warhol

Director Thomas Sokolowski with U.S. Senator

Arlen Specter at the opening for the recent

exhibition November 22, 1963: Images, Memory,

Myth. Specter spoke at The Warhol about

his experience as a young lawyer on the

Warren Commission. |

|

|

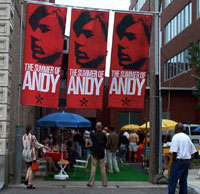

| An outdoor

party complete with hotdogs and badminton

kicked off The Summer of Andy, a season-long

celebration of the year of Andy Warhol’s

75th birthday. |

A local

artist discusses her work at the opening

of AMP at The Warhol, a showcase of Pittsburgh

area visual artists presented in collaboration

with the Sprout Fund. |

The Warhol has

also become a hub for Pittsburgh’s

underground art cognoscenti, just as Warhol’s

Factory in New York City provided an outlet

for the avant-garde, untraditional set. “It’s

The Warhol, so it’s cool,” Peduto

says.

Cool quotient is a major concern in a

city desperately trying to attract and retain

a

young professional crowd—an imperative

if it expects to reverse population

losses, maintain its tax base, and lure new,

job-producing businesses.

It certainly has generated

development on Pittsburgh’s

North Shore. As one of the first organizations

to call the Allegheny River section of the

North Shore home, The Warhol is a strong anchor

to developers and is credited with being one

of the pioneers in the rebirth of the entire

area.

Bill Flanagan, chief communications officer

for the Allegheny Conference on Community Development,

says one of the reasons Alcoa built its headquarters

on the North Shore was to be close to The Warhol.

In fact, he and Peduto are both convinced the

city would not have one of its newer jewels—the

Pirates’ PNC Park—if The Warhol

were somewhere else.

Breaking Barriers, Creating Change

Creating opportunities for freedom of expression

is another important aspect of The Warhol’s

mission, and museum Director Thomas Sokolowski

wins unanimous praise for turning that objective

into reality.

One reason Warhol is considered

such a pivotal figure in the art world and

popular culture

in general is because he busted the barriers

between high and low art. And in the process

of questioning established values, he redefined

common notions of what art is all about.

Sokolowski’s

fans say he performs a similar role for Pittsburgh.

Using the mantle of respectability

provided by the museum’s stature as an

art institution, Sokolowski is able to follow

Warhol’s example in searching for the

cutting edge of art and society—and occasionally,

jumping over that edge. Says Potter: “The

tendency in Pittsburgh is, ‘Let’s

put up some art that’s inoffensive that

everybody can feel warm and fuzzy about.’ And

what Tom’s saying is, ‘The only

purpose of art isn’t to feel warm and

fuzzy about it.’”

Potter describes

Sokolowski as something of a gadfly, unafraid

to offer his opinion—an

important role “in a city not used to

having gadflys.” Adds Peduto: “He’s

created a debate not only around art, but also

around cultural and political issues that had

been missing.”

Sokolowski wins kudos

for using an exhibition of Warhol’s electric

chair series as an opportunity to generate

discussion about

controversial death penalty laws. An even more

disturbing exhibition, Without Sanctuary:

Lynching Photography in America, was designed

with the specific intent of providing a deeper

awareness—and

even provoking outrage—in order to stimulate

dialogue and, ideally, greater understanding

of the issue of race relations in this country.

That

2001 exhibition is regarded as a milestone

in The Warhol’s history, not only for

its bravery in presenting images and raising

issues many museums would not have touched,

but also because it provided a different perspective

of a museum’s function in a community.

To help the public tackle the unsettling emotions

and complex issues triggered by the exhibition,

The Warhol partnered with many groups outside

of the museum. Forums, films, performances,

video diaries, and a daily public dialogue

also helped visitors work through, both alone

and with others, the disturbing feelings caused

by the photographs. That

2001 exhibition is regarded as a milestone

in The Warhol’s history, not only for

its bravery in presenting images and raising

issues many museums would not have touched,

but also because it provided a different perspective

of a museum’s function in a community.

To help the public tackle the unsettling emotions

and complex issues triggered by the exhibition,

The Warhol partnered with many groups outside

of the museum. Forums, films, performances,

video diaries, and a daily public dialogue

also helped visitors work through, both alone

and with others, the disturbing feelings caused

by the photographs.

“People’s thought

processes have to have changed after seeing

that,” says

the Urban League’s Lee Hipps of Without

Sanctuary. Photo:Terry Clark

“

The lynching display did a great deal to give

me a different feeling about the museum,” says

Lee Hipps of the Urban League of Pittsburgh. “Having

seen it gave me a greater appreciation for

what my ancestors had to go through for us

to be where we are today. People’s thought

processes have to have changed after seeing

that, and those sort of things are going to

help us move forward.”

As Flanagan observes, “Isn’t that

the role of a cultural institution—a

good one—to shake things up?”

Back to Contents |