Defiance Despair Desire

20th-Century German Expressionists

Revive the Art of Printmaking

By Lorrie Flom

“One

feels the pulse of an artist when one contemplates

his graphic work.…The needle, the crayon, the

cutting knife are simpler and therefore more penetrating

means of expression than brush and color.” These

words from German artist Gustave Schiefler capture

the essence of the German Expressionist movement—an

attempt by artists during the early decades of the

20th century to communicate the depths of human experience,

primarily through printmaking.

This

woodcut depicts a 12-year-old girl named Fränzi

(Lina Franziska Fehrmann), one of many children

who frequented the Brücke communal studio.

Heckel and the other Brücke artists preferred

Fränzi’s awkward yet natural positions

to the artificial stances of professional models. This

woodcut depicts a 12-year-old girl named Fränzi

(Lina Franziska Fehrmann), one of many children

who frequented the Brücke communal studio.

Heckel and the other Brücke artists preferred

Fränzi’s awkward yet natural positions

to the artificial stances of professional models.

Erich Heckel, German, Stehendes

Kind (Standing Child), 1910/11, color woodcut, Marcia

and Granvil Specks Collection

German Expressionism

is one of the major printmaking movements of

the 20th century, according to Linda Batis,

Carnegie Museum of Art’s associate curator

of fine arts. “Although some of these artists

worked as painters and sculptors as well, they all

considered

printmaking to be critical to their work,” says

Batis. Drawing on a 400-year-old tradition of German

printmaking, German Expressionist artists “spontaneously

reinvented the medium,” she explains. Visitors

will be able to experience the power and raw beauty

of German Expressionist prints when the

exhibition

Defiance Despair Desire: German Expressionist Prints

from the Marcia and Granvil Specks Collection opens

at Carnegie Museum of Art on June 12. This exhibition,

organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum, presents

prints by 32 artists, including such luminaries

of the German

Expressionist movement as Käthe Kollwitz,

Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Max Pechstein, and

Emil Nolde.

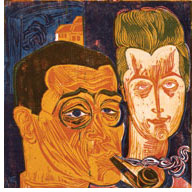

Conrad

Felixmüller, an artist and political activist

from Dresden, founded the publication Menschen (People)

to discuss the plight of European workers following

the war. In the 1920s he depicted the life of workers

in the industrial Ruhr River Valley, but often he used

his

own family as subject matter. Conrad

Felixmüller, an artist and political activist

from Dresden, founded the publication Menschen (People)

to discuss the plight of European workers following

the war. In the 1920s he depicted the life of workers

in the industrial Ruhr River Valley, but often he used

his

own family as subject matter.

Conrad Felixmüller,

German, Selbstbildnis mit Frau (Self-Portrait with

Wife), 1920/1921, Milwaukee

Art Museum

Concerned

with such universal issues as war, death,

inequality and injustice, the alienation of

city life, and man’s relationship with nature,

these artists were inspired by the bold, primitive,

and expressive

styles of Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, and Vincent

van Gogh. “If you look at the woodcuts

of German Expressionist artists, they’re

unrefined yet beautiful,” says Batis. “These

artists weren’t especially concerned with

developing highly skilled technique. They were

more concerned

with expressing themselves as spontaneously as

possible.” In

fact, many of these artists were untrained in

the medium, yet carved, printed, and distributed

their

woodcuts

themselves, seeking to communicate with the broadest

audiences possible. Along with reviving the woodcut

as an expressive medium, German Expressionist

artists also utilized such time-honored printmaking

techniques

as etchings, aquatints, drypoints, and lithographs. The

works in Defiance Despair Desire capture a

period of tremendous social unrest in pre-

and

post-World

War I Germany. Batis says, “This is a beautiful

show that surveys the subject very thoroughly.” Among

Batis’ favorite works in the exhibition

are the color woodcuts by Erich Heckel that she

describes as, “very

bold, simplified, and extremely powerful,” and

the works of Emil Nolde, which she calls “wonderful

prints, very experimental. He was a real craftsman.”

Museum visitors also will have an opportunity

to explore the earliest roots of German printmaking

in a companion

show featuring 65 prints from 15th-and 16th-century

Germany that are part of Carnegie Museum of

Art’s

permanent collection. “I think it will be fascinating

for visitors to see how printmaking started out 400

years earlier,” says Batis. The 20th-century

German Expressionist prints are “fresh and different…astonishing

really,” she adds. “It’s almost as

if they went back to the 15th-century craft and said, ‘let’s

reinvent it.’”

UPDATE:

The Best Minds in the Business Help Shape the

2004 Carnegie International

Since its earliest years, the Carnegie International

has drawn on the expertise of an international advisory

committee to select artists and artworks. Laura Hoptman,

curator of the 2004 Carnegie International, says that

the committee’s contributions are invaluable: “One

individual can’t know what is going on throughout

the world. Advisors are our eyes and ears.”

Typically,

the committee members are chosen by the curator.

Laura has known each of her committee members

over the past decade through her curatorial work

at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City

and

elsewhere. Her international “dream team” includes:

Francesco Bonami, curator of contemporary art at

the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and curator

of

the 2003 Venice Biennale; Gary Garrels, chief curator

of drawing at MoMA; Japanese art critic Midori Matsui;

Cuauhtemoc Medina, a professor of art criticism and

a curator in Mexico; and artist Rirkrit Tiravanija,

a professor at Columbia University whose work appeared

in the 1995 Carnegie International.

The committee

members offer different perceptions of international

art and provide important feedback

during

the three years of preparation for the exhibition.

Besides meeting three or four times to view slides

and discuss artists and works, committee members

keep in close contact by email, sharing images

and ideas.

For this International, each committee member also

contributed articles about different artists for

the exhibition’s catalogue.

Although the

Carnegie International has a single curator,

Laura says it could not succeed without

this international

committee working in concert. “It’s

extraordinary to get so much expertise together

for one exhibition,” she

says. “The International is curated by one

individual, but not without the help of some of

the best minds

in the business.”

More Aluminum by Design

A New Exhibition Highlights Recent Acquisitions

April 17 - August 8,

2004 • Forum Gallery

Isamu Noguchi, designer

American, Pair of Alcoa Forecast Program Tables, 1957,

aluminum,

gift of Torrence M. Hunt Sr.

Aluminum

may be the most abundant metal on earth, but it wasn’t

until the

last 100 years or so that aluminum’s versatility,

light weight, and beauty were widely explored by

manufacturers and designers. That period

of discovery led to many of the greatest design and

construction advances of the 20th century, a fact

that was not lost on Carnegie Museum of Art, which

began to seriously collect designed objects made

from aluminum in 1997, in the process

of organizing the exhibition, Aluminum by Design:

Jewelry to Jets.

Since its closing in Pittsburgh

in 2001, the exhibition has traveled to such cities

as Paris, Montreal, London,

Brussels, New York, and Miami. As a result of the

tour’s success, the Museum of Art is recognized

as one of the leading collectors of aluminum design,

and it remains committed to enhancing its collection

of aluminum objects.

More Aluminum by Design, on

view in the Forum Gallery through August 8, features

some of the more significant

and fascinating aluminum design objects that

have been acquired by the museum, either by gift

or

purchase, since the 2000 exhibition opened. “Aluminum

is an amazing material that designers have reveled

in exploring and exploiting,” says Sarah

Nichols, curator of decorative arts. “This

attraction is captured by the varied, fascinating,

and important

objects in the museum’s collection.”

A

pair of tables designed by Isamu Noguchi in

1957 for Alcoa and a credenza designed by The

German

Fire Proofing Company in 1958 for Reynolds

Metals are

among the objects that Nichols says are outstanding

examples of the aluminum industry’s promotion

of the metal’s use in designed objects.

Another piece from the 1950s is a two-piece dress

made of

aluminum thread and rhinestones. And for

a more contemporary twist, there is a screen

made in 1993 by Brazilian brothers Fernando

and Humberto

Campana from recycled television antennas.

Recent Aquisition:

Allegory of Life by Giorgio Ghisi

Giorgio Ghisi, Italian, Allegory

of Life (The Dream of Raphael), 1561, engraving,

Charles J. Rosenbloom and Leisser Art Fund

Giorgio Ghisi is considered one of the most important

mid-16th-century Italian engravers. When Curator

Linda Batis found an outstanding impression of Ghisi’s

most important print, Allegory of Life, she jumped

at the opportunity to acquire it for Carnegie Museum

of Art. “These major prints are becoming impossible

to find,” says Batis. “They’re

rare on the market. So, when a museum has an opportunity

to acquire one, it is an opportunity not to be missed.”

Allegory of Life is a large, complex work that has

never been fully deciphered. For more than 400 years,

commentators have struggled with the interpretation

of this work. Despite their differing views, they

all agree the message is a hopeful one.

Batis said

this particular print fits in well with Carnegie

Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

The museum has very important examples of Italian

printmaking, including Andrea Mantegna (late 15th

century) and Giulio Campagnola (early 16th century),

says Batis. “One of the things I’ve tried

to do is to create a historical continuum of printmaking

in the museum’s collection. By adding certain

landmarks, such as this Ghisi print, it’s possible

to survey the medium,” she explains. “In

addition, this print really is gorgeous.”

Back to Contents |