Albert Bierstadt, American, 1830-1902,In

the Mountains, 1867, oil on canvas,

The Wadsworth Atheneum

Museum of Art

By

Ellen S. Wilson By

the 19th century, industry was changing forever

the way people lived. Many of the forests in the Old

World had been cut and burned, machinery ran on coal,

and most people in England lived in urban areas rather

than on farms. The New World was not to be left behind—there,

too, cities were expanding, forests were leveled, and

human domination of the natural world was America’s

Manifest Destiny, a goal ordained by God. Ironically,

during this time an appreciation for the beauties of

nature, captured by landscape painters and photographers,

took hold of the public imagination. Americans bragged

about the grandeur of their trees, even as they cut

them down.

Opening February 21, two exhibitions at Carnegie

Museum of Art illustrate the mindset of artists and

thinkers

in the New World. Hudson River School: Masterworks

from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art contains

55 masterpieces from the best collection of Hudson

River School paintings in the world. Eloquent

Vistas: the Art of 19th-Century American Landscape

Photography

from the George Eastman House Collection, Rochester,

New York, is a survey of the American landscape photograph.

Together, these exhibitions seize a moment when America

was all potential, when frontiers were still waiting

to be explored, and leaving a mark on the wilderness

was a noble pursuit.

Hudson River School:

Masterworks

from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Thomas Cole, American,

1801-1848, Scene from "The Last of

the Mohicans," Cora Kneeling at the Feet

of Tamenund, 1827, oil on canvas, The

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

The Power of Landscape Paintings

America’s first school of landscape

painters arose from a natural awe of and

respect for the wonders

of the new continent. “This was the first self-conscious attempt

to make American landscape paintings,” says

Louise Lippincott, curator of fine art at Carnegie

Museum of Art. “There

was a deep interest in specifically American scenes—they

really became images of patriotic optimism.”

The

unexplored vistas were so much bigger and freer

than the comparatively tame and manicured English

countryside. The Hudson River school painters explored

the Connecticut

River, Niagara Falls, and Lake George in upstate

New York—the territory memorialized by novelist

James Fenimore Cooper in his Leatherstocking

Tales.

The land

at its moment of transformation from wild to tame

was a dynamic subject. Early in the century, the

natural

world was a powerful force; by the end, nature

had been largely subjugated to human will.

The arrival

of painter Thomas Cole in New York

City in 1825 marks the beginning of the Hudson

River school,

which lasted until about 1870. The core of

the collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum

of

Art was formed

by two patrons, Daniel Wadsworth (1771-1848),

who founded the museum, and Elizabeth Hart

Jarvis Colt

(1826-1905),

widow of arms manufacturer Samuel Colt. Both

patrons commissioned many of the works in

the collection.

“

This is a masterpiece show,” says Lippincott. “These

are great pictures, probably the best collection

of this school of painting in the country.

People should

come in and be prepared to revel in the splendor

of it.”

And splendid these works are,

both in technique and subject matter. Niagara

Falls, painted

by Cole’s

apprentice Frederic Edwin Church in 1856, is

emblematic of the school as it captures the

awe-inspiring power

of the water, the ever-present rainbow, a small

watchtower, and three tiny houses—reminders

that man is insignificant in the face of natural

forces. The Falls themselves

were already a national icon, a reminder that

this young country had more powerful waterfalls,

bigger

trees, and untamed wilderness than the continent

most of its inhabitants had left behind. With

the opening

of the Erie Canal in 1825, Niagara Falls was

a popular tourist destination, and nearly every

landscape painter

of this period painted it. This exhibition

alone includes paintings of the Falls by John

Trumbull, John F. Kensett,

Alvan Fisher, and Thomas Chambers, in addition

to Church.

Masters of the Earth

Thomas Cole, reflecting on the opportunities for painters

in this country, remarked “All nature here

is new to Art,” adding the scenes of Europe

were “hackneyed and worn by the daily pencils

of hundreds,” but for the American painter,

the forests, lakes, and falls “had been preserved

untouched from the time of creation for his heaven-favored

pencil.”

David Johnson,American,

1827-1908

Study, Franconia Mountains from West

Campton, New Hampshire, c.1861-63,

oil on canvas,The

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Cole found special inspiration in Cooper’s

tales of the steadfast scout Natty Bumppo, or Hawkeye.

One

of his more famous works illustrates a climactic scene

from The Last of the Mohicans, in which a young woman,

one of several English people kidnapped by an American

Indian, pleads for mercy from the wise old chief Tamenund.

In the novel, the scene is all cunning talk, manipulation,

and ritual diplomacy, as the evil Indian Magua bargains

for his prisoners. In Cole’s interpretation,

these human events are nothing in the face of the

majesty of the mountains. While Cooper set the

scene in the

area around Lake George, Cole drew on the White

Mountains of New Hampshire as a more fitting backdrop. “The Hudson River painters freely rearranged

the topography to improve the landscape,” explains

Lippincott. “The

goal was to create a strong emotional reaction

in the viewer.”

The novel ends as Chingachgook,

the grieving father of the recently murdered

last Mohican, states, “The

pale-faces are masters of the earth and the time

of the redmen has not yet come again.” Cole,

in his painting, complicates this statement,

for who can

ever master this awe-inspiring place? The round

boulder perched on the pinnacle in the background

serves to

remind the viewer of how small the human inhabitants

are and how temporary their stay.

Hudson River School: Masterworks from the

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art has been organized

by the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford,

Connecticut. The national tour is sponsored

by MetLife Foundation.

Generous

support for the exhibition’s

presentation in Pittsburgh has been provided

by The Laurel Foundation. Additional support

has been provided by The Fellows and Associates

Funds of Carnegie Museum of Art.

Eloquent Vistas:

Documenting

the Disappearing Wilderness

Eadweard Muybridge,

American, 1830-1904, The Domes from Merced

River,

Yosemite Valley, c.

1874, albumen print, George Eastman House

Just as the Hudson River painters manipulated

the scenery they painted, photographers also

created a scene by the act of choosing and

framing it. And here too, the irresistible

appeal of Niagara Falls, as well as other natural

sights, were popular subjects. As many of the

photographs were taken later in the century,

they also document great changes in the continent,

the building of the railroads, and the battlefields

of the Civil War, as the country struggled

to establish its identity.

Early landscape photographers

had to face physical challenges and manage

cumbersome technology

that painters did not. Until the 1880s, photographers

had to prepare the negative just before exposure,

and then immediately develop and fix it while

the chemicals on the plate were still damp,

necessitating the presence of some sort of

traveling darkroom. And because enlarging

was expensive, most photographers made contact

prints by placing the negative directly on

the contact paper, making the finished print

the same size as the negative. The photographs

in Eloquent Vistas are all contact prints

made

in this way, and as the scenery of the period

seemed to require large photographs, the

cameras used to take the pictures had to be

even larger.

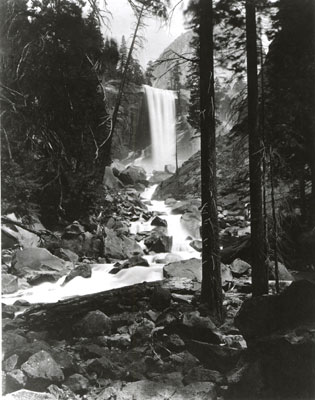

Eadweard Muybridge,

American, 1830-1904, Vernal Fall, 350

Ft., Yosemite Valley, c. 1874, albumen

print, George Eastman House Eadweard Muybridge,

American, 1830-1904, Vernal Fall, 350

Ft., Yosemite Valley, c. 1874, albumen

print, George Eastman House

But the very act of photographing

the wilderness, especially the western wilderness,

changed

both the public perception and the use

of it. The development of trains and telegraphs

brought

tourists, lured by the pictures made along

the route of the railroad tracks. It was

photographs of Yellowstone that led President

Ulysses Grant

to sign a bill in 1872 protecting its natural

state, and photographs also led to the

conservation

of Yosemite. By the end of the century,

an industrial aesthetic replaced the natural

one. The

frontier was

more accessible and less mysterious.

American artists concentrated on urban subjects,

studied the human figure, and turned

away

from broad

views of the disappearing wilderness.

Eloquent

Vistas: The Art of 19th-Century American

Landscape Photographers from the George Eastman

House Collection has been organized by the

George Eastman House International Museum of

Photography and Film. Generous support has

been provided by The William Talbott Hillman

Foundation, Inc. and the W.P. Snyder III Charitable

Fund.

A concurrent exhibition from the Yale Center

for British Art also looks back to works inspired

by a search for national identity.

The Romantic Print in Britain

James Gillray (1757-1815), The

Death of the Great Wolf, 1795, etching and engraving with hand-coloring,

Yale Center for British Art.

The Romantic Print in Britain (1776-1880)

covers a period that includes the American War

of Independence,

the French Revolution, the Napoleonic wars,

and the growth of the British Empire, which led

to

an increased slave trade as well as to colonies

in America, India, the South Seas, and the

Caribbean. The prints in this exhibition illustrate

these

conditions, as well as the Romantic obsession

with celebrities and historic events.

Unlike

the Hudson River school landscapes, these prints

dwell more on intellectual subjects and

the life of the mind. The printmaking process

itself is less spontaneous than painting

or photography, and the exhibition includes tools,

plates, and

progress prints to illustrate the evolution

of a specific image.

“By the 19th century, collecting prints

in Britain was a well-established practice,” explains

Linda Batis, associate curator of fine art

at Carnegie Museum of Art, whose speciality

is works

on paper. “These prints were intended

to be purchased by the public.”

The

Death of General Wolfe, 1776, by William

Woollett (1735-1785), a line-engraving with

etching, is typical both in subject matter

and in process.

Benjamin West’s (1738-1820) original

painting of the death of Major-General James

Wolfe at

Quebec in 1759 was a romanticized version

of a historically important event. The painting

was instantly popular, and the engraving

of

it by Woollett was published four years later

and

sold by subscription. Woollett was considered

the best engraver in England, and his role

in producing the print increased the importance

of the painting.

“The photographer and the painter were

more immediately in touch with the actual subject

than the printer

making a print from a painting,” says

Batis. “But

the prints, photographs, and paintings all

have something of a concern with the heroic

in them.

Whether landscapes or individual portraits,

the places, people, and events are larger

than life.”

The

Romantic Print in Britain has been organized

by the Yale Center

for British Art. The exhibition’s

presentation in Pittsburgh has been generously

supported by the Gailliot Family Foundation.

General

support for all the museum’s exhibition

programs is provided by The Heinz Endowments

and the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.

Back to Contents |