Exhibit Update:

Placing Dinosaurs in Their World

The world’s premier home

for dinosaurs requires space and time.

R.J. Gangewere R.J. Gangewere

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Director Bill DeWalt

says that creating the proper space for the new Dinosaurs

in Their World exhibit “is taking a great deal

of time and thought to ensure that we have the proper

phasing and best locations for all that we have to

move.”

The museum has re-examined the best uses

of space for the public areas, the collections, and

research areas,

and the “back of the house” operations.

The goal is to create more public space within the

historic building, better protect the collections,

and, where possible, move business operations out

of the building.

To make room for Dinosaurs in Their

World, it is

imperative to move the Natural History Library

to a location where

it will serve as “the physical and philosophical

core of the research and collections areas,” says

DeWalt. The most likely location for the library

is in the rear of the first floor.

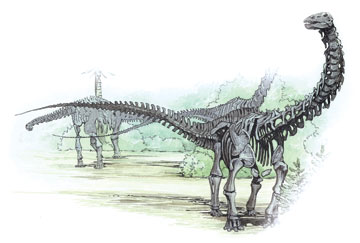

An

artistic vision of the future Dinosaurs in Their World

exhibit is captured in models and illustrations at

the entrance to the current hall. An

artistic vision of the future Dinosaurs in Their World

exhibit is captured in models and illustrations at

the entrance to the current hall.

The museum will

also use this period of change to upgrade its

scientific collections and research

areas.

The

Invertebrate Zoology (bugs) and Botany collections

will be air-conditioned and collections will

receive better protection. The museum is also applying

for a separate grant to provide climate control

for the

fossils stored in the basement to protect these

invaluable specimens as the national treasures

that they are. Looking ahead, DeWalt says that

in the spring of 2004 the architect for the new hall

will be

selected,

and

significant construction will begin in early

2005. Time will be needed not only for construction

and for moving departments,

but also

for dismantling the famous dinosaur specimens,

and then reconstructing them according to modern

scientific

standards. By some time in 2007—on the

100th anniversary of expansion of the museum

into the present

building—the newly constructed atrium

for the dinosaurs is expected to open. The

renovated existing

Dinosaur Hall will probably not open until

late 2008 or early 2009.

“

It is truly gratifying to me to know that leaders in

our community see this expansion just as we do—as

the creation of a first-day attraction for Pittsburgh,” says

DeWalt. “These leaders understand that the Museum

of Natural History is a world treasure. They want to

invest in a great exhibit that reflects the world-class

standards of our science.”

Dinosaurs in Their World Funding Tops $25 Million

October 2003 was a big month for the Dinosaurs

in Their World project, starting with the announcement by

Eden Hall Foundation that it would give a lead gift

of $5 million in support of the creation of the world’s

premier dinosaur exhibits.

The Heinz Endowment soon

followed with an announcement of its gift of $4

million, which is the first but not

the last it plans to give to the Carnegie Museums

Campaign. “The

educational, economic development, and cultural benefits

of this project are incredibly far-reaching,” says

Maxwell King, president of The Heinz Endowments,

of the Dinosaur Hall project. “Pittsburgh has

the opportunity to create something that is truly

one-of-a-kind,

and that's exciting.”

Another $500,000 gift

from the Walton/Whetzel Family, and an anonymous

gift of $250,000 have brought Carnegie

Museum of Natural History ever closer to its fundraising

goal of $35 million for creating Dinosaurs

in Their World.

February

7 – August 15, 2004

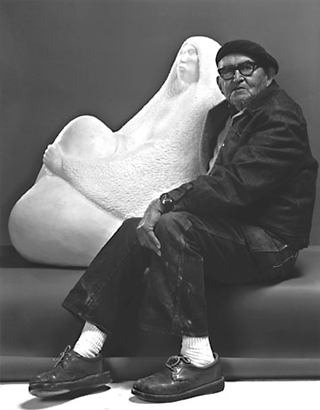

Allan Houser (1914-1994) has been credited with

reviving the art of stone sculpture in the United

States. In 1992 he was awarded the National Medal

of Arts by President George Bush, becoming the

first Native American to receive the nation’s

highest honor for artists and joining the ranks

of luminaries such as Georgia O'Keeffe, Marian

Anderson, Ella Fitzgerald, and Aaron Copeland. Allan Houser (1914-1994) has been credited with

reviving the art of stone sculpture in the United

States. In 1992 he was awarded the National Medal

of Arts by President George Bush, becoming the

first Native American to receive the nation’s

highest honor for artists and joining the ranks

of luminaries such as Georgia O'Keeffe, Marian

Anderson, Ella Fitzgerald, and Aaron Copeland.

Monumental,

intimate, and steeped in history, his sculptures

have been internationally acclaimed

and are included in collections of the Smithsonian

Institution, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris,

the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the White House,

and the British Royal Collection. In 1985 his

monumental bronze Offering of the Sacred Pipe was

dedicated

at the United Nations building in New York City.

Houser’s

first commission for a sculpture in 1949 came

from the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas—a

memorial in stone of Indian servicemen killed

in World War II. He later received a Guggenheim

grant in sculpture and

painting. "When I won my Guggenheim fellowship, I said I wanted to become

one of the best—whether painter or sculptor—in the world. That's

what my efforts are going to be, whether I get there or not," Houser

said.

A Chiricahua Apache, Houser was born on his parents'

government-grant farm in Apache, Oklahoma in 1914,

as the tribe was emerging from 27 years

in forced

exile

from their native mountains in the Southwest. His father, Sam Haozous,

was captured with Geronimo in 1886, and later served

as the great chief's interpreter.

Allan

grew up listening to his father play the drum, sing medicine songs, and

tell the stories of Geronimo.

The Sculptures of

Allan Houser features bronze and stone

sculptures, and original drawings and sketches.

A feature

of the exhibit is the thematic

development

of Houser’s bronze portrayals of the Chiricahua Apache Mountain

Spirit Dancer. Dominating the installation is a spectacular monumental

version

of Spirit of

the Wind (1992) with its soaring abstract atmospheric forms. The exhibit

is made possible by an anonymous donor and the Houser Foundation.

Tim Pearce, Mollusk Specialist

Finding clues to the environment

in snails, mussels and slugs

Tim Pearce, assistant curator of mollusks

at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, is one of the leading specialists

in the world on mollusks,

and Carnegie Museum of Natural History has one of the most important

mollusk collections in the United States.

Mollusks such

as clams and snails, as well as soft-bodied animals like slugs,

are key

animals in the world-wide food chain, as well

as critical indicators of environmental

conditions. They are among the first to give warning signs of water

pollution and degradation,

and of the reverse—the renewed health in streams, wetlands,

marshes, ponds, and lakes. Their return to the rivers around Pittsburgh

is a success story. Historically, the freshwater mussels of the

Upper Ohio watershed were used commercially for button making,

as well

as collected for their beauty.

Tim

Pearce (right) shows a land snail to a visitor at the Bioforay at

Powdermill Nature Reserve. Tim

Pearce (right) shows a land snail to a visitor at the Bioforay at

Powdermill Nature Reserve.

PHOTO:MINDY MCNAUGHER

Pearce’s

own research on the distribution of land snails has ranged from

the Kuril Islands

of Eastern Russia and Madagascar to

the State of Washington, and the Michigan islands. Regionally,

he is an expert on mollusks found in the Delmarva Peninsula

(the peninsula

on Chesapeake Bay) defined by parts of the states of Delaware,

Maryland and Virginia. The

museum’s mollusk collection goes

back to the 19th century and contains more than three million

specimens, including 1,100 type

specimens that first identified the species.

When in 2003

one of the museum’s educators brought a snail

to Pearce for identification, Pearce immediately recognized

it as a giant African snail, Achatina fulica, a federally listed

pest species.

This snail had grown to 4.5 inches in a year after the educator

found it in a park in Upper St. Clair. A voracious eater, Achatina

fulica reproduces easily, and has a history of damaging crops

once it is established. In November, Pearce and experts from the

federal

government

and the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture searched

the park and found no more Giant African snails. But they will

return

in the

warmer weather to check again. Someone apparently had kept

this snail as a pet and then released it in the park. Pearce advises

that people “keep

their pets, even if they do not have big eyes and hair,” until

they die.

“

Land snails get around,” he adds. “They raft on material

in streams, ride on the feet or feathers of birds, or on leaves blown

by the wind.” One of his goals is to make the museum’s

collection of snails available to scientists on the internet. Another

goal is to identify fully all the species of slugs that live in Pennsylvania—another

creature that scientists view as a sensitive barometer

to the environment.

Cynthia Morton, Botanist

Molecular biology for oranges, limes,

and beans

Cynthia

Morton (left) discusses native plants at Powdermill

Nature Reserve. Cynthia

Morton (left) discusses native plants at Powdermill

Nature Reserve.

PHOTO:MINDY MCNAUGHER

The associate curator and head of the section of botany,

Cynthia Morton, is an expert on the molecular and

genetic makeup of citrus plants such as lemon, grapefruits,

oranges, and mandarins. Her research has strong agricultural

and economic implications as she seeks to further

define

the genetic basis of these plants. The orange-growing

industries of Florida, California, and Australia,

for example, seek cold tolerant and disease resistant

plants,

and her research is the kind that can discover where

to look for disease resistant genes or cold tolerant

rootstocks. But Morton also believes that, given

the 160 or so different forms of citrus plants, oranges

could grow in more northern regions if the right

combination

of rootstocks and genetic makeup were combined. Another

of her projects involves work with a colleague from

Benin in Africa. They have just published the

first genetic map for the rotational crop velvet

bean. They hope to develop a new form of the velvet

bean

(Mucuna) as a rotational crop for Africa, South America,

and the southern United States—a plant that

is very important because of its nitrogen-fixing

capabilities

and its potential use as a food source. She notes

that molecular biology of the kind she practices

is not

done easily in most third-World countries.

Another

of her interests is bio-remediation of the environment—cleaning

up contaminated sites with naturally occurring

bacteria as opposed to more expensive

and labor-intensive techniques.

As a skilled molecular

systematist with a Ph.D. in Biology, Morton could

work in industry or at

a university,

but she feels that the museum gives her flexibility

to focus on conservation, and on genetically

diverse plant species of value to everyone. The museum’s

Molecular Laboratory is very important to her: “We’ve

come so far in technology that I can now do molecular

research without radioactivity, and I can do in

two and a half hours what would have taken me a

week and

a half to do not so many years ago.” But

she also says as she heats a brew of beef juice

and plant

chemicals in beaker dishes, “A lot of this

physical research is not that difficult—it

can be done manually. People are often wrongly

intimidated by technology.”

Back to Contents |