By R.J. Gangwere

It was 100 years ago that the Harwick

Mine disaster near Springdale, Pa., claimed 181 lives,

and prompted Andrew Carnegie to create a fund that

would honor civilian heroism. One of the worst mining

disasters of the century, the Harwick explosion,

which occurred not far from Pittsburgh, preyed on

Carnegie’s mind, especially since two of its

victims had entered the mine after the explosion

in fatal attempts to assist others.

It was the early

morning of January 25, 1904, when the Allegheny

Coal Company’s mine exploded.

After the explosion, mining engineer Selwyn Taylor

hurried from his Pittsburgh office and descended

into the mine with two other men to attempt a rescue.

A 16-year-old boy—the only survivor—was

brought up, but Taylor died from poisonous gases

he had inhaled.

The day after the explosion, coal

miner Daniel A. Lyle answered an appeal for volunteers

and rushed

to the scene from Leechburg, a small town 15

miles away. Although he suffered asthma and was aware

of

the dangerous conditions in the mine, Lyle and

two other men worked from late afternoon well

into

the

night, going deeper into the mine than other

volunteers to look for survivors. The other two men

surfaced

the next morning, but Lyle was fatally overcome

by mine gases.

Carnegie’s friend, Richard

Watson Gilder, the influential editor-in-chief

of the Century Monthly

Magazine, had sent Carnegie a poem, about which

Carnegie said, “I re-read it the morning

after the accident, and resolved then to establish

the Hero Fund.” Carnegie

was an outspoken pacifist, and the poem expressed

his conviction that in peacetime, the “heroes

of civilization” were as important as

the heroes who performed acts of valor in wartime.

Accordingly,

he set aside $5 million under

the care of the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission

in

Pittsburgh to honor the heroes of civilization

and to provide

financial aid to those disabled by their spontaneous

acts of heroism or to the dependents of heroes

killed

while helping others. Unlike policemen, firemen,

or people in the military, the heroes selected

by the Carnegie Commission are not paid or

required to help others, but instead are ordinary

citizens

who act spontaneously in a crisis and are ready

to risk their own lives to help others.

Headquartered

in Pittsburgh, the commission investigates heroic

acts in Canada and the

United States.

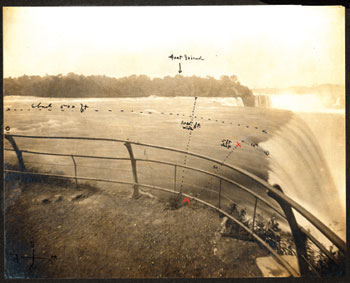

The hallmark of its investigative process

has always

been the “scientific” documentation

of a heroic act before making an award.

For a century, the heroic actions rewarded

by the commission have been the stuff of

high drama.

In

early decades, heroes saved people trapped

in mines and wells, caught in machinery or

burning

houses,

or about to be trampled by runaway horses,

or struck by an ice flow. In more recent

decades, automobiles

figure more prominently, as do weapons. One

hero

pulled a victim from a burning car about

to explode; another dragged a trapped person

from

a vehicle

on railroad tracks moments before a train

demolished it.

Still, the old crises persist,

as a modern hero saved a 2-year-old from

raging waters,

while

another rescued

a 70-year-old trapped several miles within

a raging forest fire by driving an SUV

into the

inferno.

Locally, in 2002 in nearby Clairton, Pa.,

a man leaped from

a car to assist a police officer who had

been shot seven times while apprehending

a criminal;

and

in Alaska, a reading teacher saved his

students from

a slashing attack by overpowering a crazed,

knife-wielding man.

Pittsburgh Heroes

Pittsburgh was a deliberate choice by Carnegie as

the home for the Carnegie Hero Commission. Not

only was it the city where he had lived, become

a businessman, and made his fortune, but also it

was an industrial city full of dangers in the workplace,

a symbolic city where many hospitals were needed

to treat the victims of accidents in the mills

and mines.

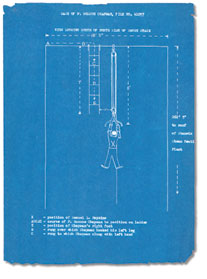

One act of local heroism occurred in

1947, involving two men painting the 260-foot

smokestack of the Stanwix

Steam Heating Plant in downtown Pittsburgh. When

Samuel Hopkins climbed down an eight-foot temporary

ladder hanging from the top of the stack and moved

into the boatswain’s chair from which he

worked, a strap broke and the chair fell away,

leaving him

dangling from the top of the stack and holding

onto the strap with his gloved hands, one of which

had slippery paint on it. His partner, Rosco

Chapman, climbed around the 18-foot diameter smokestack

to the work ladder, climbed down it and, hanging

on to the ladder with his legs, grabbed Hopkins

by the left wrist. Then, with his other hand he

removed

Hopkins’ slippery work-glove, allowing Hopkins

to seize the strap more firmly. By shifting and

lifting, Chapman was able to haul Hopkins up so

he could get

a grip on the ladder and climb to safety. One act of local heroism occurred in

1947, involving two men painting the 260-foot

smokestack of the Stanwix

Steam Heating Plant in downtown Pittsburgh. When

Samuel Hopkins climbed down an eight-foot temporary

ladder hanging from the top of the stack and moved

into the boatswain’s chair from which he

worked, a strap broke and the chair fell away,

leaving him

dangling from the top of the stack and holding

onto the strap with his gloved hands, one of which

had slippery paint on it. His partner, Rosco

Chapman, climbed around the 18-foot diameter smokestack

to the work ladder, climbed down it and, hanging

on to the ladder with his legs, grabbed Hopkins

by the left wrist. Then, with his other hand he

removed

Hopkins’ slippery work-glove, allowing Hopkins

to seize the strap more firmly. By shifting and

lifting, Chapman was able to haul Hopkins up so

he could get

a grip on the ladder and climb to safety.

Another

heroic event occurred in 1960 at the Heinz plant

on the North Side when a man was saved from

suffocation inside a large tank car nearly emptied

of tomato paste. Climbing down through the 20-inch

hatch on the tank car by an interior ladder,

34-year-old Joseph Buttice was overcome by the nitrogen

used

to preserve the paste and slumped forward into

the paste remaining at the bottom of the car.

While the

supervisor ran for an air hose and assistance,

a cook’s helper named Stephan Jagusczak

tried to rescue Buttice from inside the car,

but was

also overcome by the gas. Then a preparation

helper named

Peter P. Smoley put on an air mask and descended

into the car with a rope around his waist and

another rope to secure the two unconscious men

at the bottom.

He roped them, which enabled them to be hauled

up. But Smoley, too, was overcome. Buttice was

in the

car the longest, but he did survive thanks to

his rescuers. Both Jagusczak and Smoley died,

and their

families received recognition of their heroism

from the Hero Commission.

A third instance occurred

in 1986, in the parking lot outside the Mellon

Arena after a Pittsburgh

Penguins Hockey game. Andrew Wray Mathieson

and his wife were

leaving after the game with their friend, Jane

Celender, when they were approached by Celender’s

estranged husband. A large six-foot man weighing

250 pounds,

he ordered Celender into his car, and when

she ran, he fired a .38-caliber handgun at

her from

10 feet

away, striking her purse. Mathieson tackled

the husband and was shot twice in the chest

in the

process. After

his wife secured Celender’s safety and

returned to help her husband, she, too, was

shot in the chest.

After this, the gunman returned to his car

and shot himself. Both Mr. and Mrs. Mathieson

recovered

from

their wounds, and when Andrew Mathieson died

15 years later at age 72, the lengthy obituary

of this quiet,

widely-respected man—a financial advisor,

corporate director, and foundation executive—noted

that his “confidence in himself was no

greater than the trust others could place in

him.” Like

the heroes before him, he exemplified the courage

of the ordinary person in a crisis.

In establishing

his Commission in 1904, Carnegie appointed

21 Pittsburghers whom he admired

and trusted. These were people whom he wanted

to

look objectively

at an act of courage, evaluate it scientifically,

and make awards in the spirit of “scientific

philanthropy” that he advocated. To this

day, every heroic act is painstakingly verified

and recorded

in rich detail.

Ten of Carnegie’s original

Hero Fund trustees were leaders or trustees

of Carnegie Institute and

Library, and as the board membership changed

through the years, different leaders of his

educational institutions

continued to serve as trustees.

In the century since its creation, the Commission

in Pittsburgh has awarded 8,764 medals and

$27 million in accompanying grants, including

scholarship

aid

and continuing assistance. In Europe in 1908,

Carnegie established the Carnegie Hero Fund

Trust for Great

Britain, and soon after also established hero

funds in Germany, Norway, Switzerland, the

Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, and

Italy. All but

the

German fund are still active.

A Centennial

Celebration, 1904-2004

In honor of the centennial, a rare, complete suite

of Carnegie Medals—gold, silver, and bronze—kept

in the Anthropology collection of Carnegie Museum

of Natural History will be displayed at the museum

starting in late August. The set includes medals

designed and used by other countries. The exhibit

will be seen a few days earlier in mid-August at

the American Numismatic Association National Convention

held at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center in

Pittsburgh. In honor of the centennial, a rare, complete suite

of Carnegie Medals—gold, silver, and bronze—kept

in the Anthropology collection of Carnegie Museum

of Natural History will be displayed at the museum

starting in late August. The set includes medals

designed and used by other countries. The exhibit

will be seen a few days earlier in mid-August at

the American Numismatic Association National Convention

held at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center in

Pittsburgh.

The centennial celebration itself will

take place in Carnegie Music Hall on Saturday,

October 16, with

a keynote speech by the prize-winning historian

and native Pittsburgher, David McCullough. The

public is invited, and tickets are available by calling

The Pittsburgh Cultural Trust at 412.456.6666 or

visiting www.pgharts.org.

The Hero Fund also is

publishing its own story, A Century of Heroes,

in the fall of 2004, in honor

of the occasion.

Prepared with the help of Mary Brignano, co-author

of A Century of Heroes, and Douglas R. Chambers,

managing director of the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission.

Back to Contents

|