Curator

of Vertebrate Paleontology Chris Beard explains “Sampson” to

a school group. Photos: Mindy McNaugher

Samson

Comes to Pittsburgh

What will the Tyrannosaurus rex skull called “Samson” reveal?

It's hard to say. But audiences at Carnegie Museum

of Natural History will be the first to know.

Still

embedded in about a half-ton of stone matrix, the

skull is on display at the PaleoLab of the museum.

As the skull is revealed over 10 months of careful

preparation, the public will get the clearest view

yet of the head of T. rex. Scientists expect to discover

more about the dinosaur’s senses—its

vision, hearing, ability to smell—and whether

its head had any characteristics so far unknown to

science.

Once the skull is revealed, the museum will make

a mold and produce a cast for its collection.

There

are only about 30 T. rex skulls in the world,

and this new one, discovered recently in South

Dakota, has been called the most complete T. rex skull

in

existence by experts in the field of paleontology.

Unlike others, it was not distorted or fragmented after

it was buried in what was probably

an ancient riverbed, some 70 million to 67 million

years ago.

About 40 to 50 percent of the skeleton

exists, and the body of the specimen is being

removed from

the

stone by expert Phil Fraley in New Jersey. Fraley,

formerly of the American Museum of Natural History

in New York and the preparator of the large “Sue” T. rex at the Field Museum of Chicago, is now the

head of the independent company Phil Fraley Productions.

Fraley recommended that the skull itself be prepared

by the experts at “The Home of the Dinosaurs,” Carnegie

Museum of Natural History, because of the museum's

long-standing expertise on dinosaur material. About 40 to 50 percent of the skeleton

exists, and the body of the specimen is being

removed from

the

stone by expert Phil Fraley in New Jersey. Fraley,

formerly of the American Museum of Natural History

in New York and the preparator of the large “Sue” T. rex at the Field Museum of Chicago, is now the

head of the independent company Phil Fraley Productions.

Fraley recommended that the skull itself be prepared

by the experts at “The Home of the Dinosaurs,” Carnegie

Museum of Natural History, because of the museum's

long-standing expertise on dinosaur material.

Curator

Emeritus Mary Dawson says it is hard to predict

what new information will be discovered

until the

skull is prepared. We know already that T. rex had binocular

(three-dimensional) vision because of the position

of its eyes, and that it had large spaces for

its

olfactory lobes, suggesting it had a powerful

sense of smell

and, therefore, was perhaps a scavenger. Scientists

now think that its nostrils were in a more

forward position, like a snake's, than earlier reconstructions

suggested. Hopefully the new T. rex skull will

reveal more about the dinosaur’s

brain cavity, the back part of its skull,

and its palate. Curator Chris Beard notes that there

is

evidence on

Samson’s skull of something different

at the top of the head—perhaps T. rex

had a horn!

Collected on a South Dakota ranch

by a commercial group, the specimen was

sold to Graham Ferguson

Lacey, a collector

in Great Britain who plans to put it on

tour as an educational exhibit after it is prepared.

In

addition

to a cast of the skull, Carnegie Museum

of

Natural History will receive a fee for

its two years

of preparation, part of which will go towards

developing

the new

Dinosaurs in Their World exhibits.

________________________________________________________________

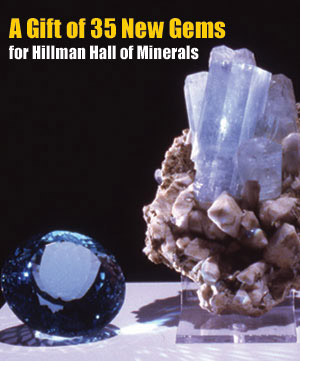

Because

of its reputation for exhibiting the highest quality

gemstones and minerals, and its prestige in

the world of mineralogists and collectors, Hillman

Hall of Minerals & Gems often attracts fine specimens

as gifts from important donors. One example is a recent

donation of outstanding specimens by Bruce Oreck of

Boulder, Colorado. His gift of 35 gemstones appraised

at over $200,000 contains important specimens that

Marc Wilson, section head of minerals at Carnegie Museum

of Natural History, says “are perfectly tailored

to fill the needs of the museum’s growing collection.” Because

of its reputation for exhibiting the highest quality

gemstones and minerals, and its prestige in

the world of mineralogists and collectors, Hillman

Hall of Minerals & Gems often attracts fine specimens

as gifts from important donors. One example is a recent

donation of outstanding specimens by Bruce Oreck of

Boulder, Colorado. His gift of 35 gemstones appraised

at over $200,000 contains important specimens that

Marc Wilson, section head of minerals at Carnegie Museum

of Natural History, says “are perfectly tailored

to fill the needs of the museum’s growing collection.”

Included

are stones that will upgrade the collection in several

areas due to their high quality and large

size, including a spectacular blue aquamarine of

379.48 carets, flawless in quality. The donation also

contains

two “watermelon” tourmaline specimens.

One has been installed in the Masterpiece Gallery

of Hillman Hall and the other is planned for a future

exhibit. Another gift of a rhodochrosite from David

Oreck can be seen in the entrance case to Hillman

Hall.

Hillman Hall has grown steadily in the beauty

of

its collections and in its international reputation

since

it opened in 1980. As part of the museum’s

current renovation of exhibit halls and research

space, and

the moving of departments to accommodate its upcoming

Dinosaurs in Their World expansion, Hillman Hall

is also being analyzed for possible expansion as

an exhibition

space. The new gifts to the collection are a sign

that Carnegie Museum of Natural History can produce

an even

more ambitious and beautiful display of minerals

and gems in the future.

Hummingbirds: Jewels in the Sky

Special

Exhibits Gallery n July 10 - September 13, 2004

Robert and Esther Tyrell are experts on Hummingbirds—he

as photographer and she as the writer of several authoritative

books on the subject.

“

It’s the greatest bird in the world,” says

Esther. Not only is it the smallest bird in the world,

but it beats its wings an average of 76 times a second

to hover in mid-air and even to fly backwards, or

upside down. Beneath their jewel-like plumage beats

a heart

that, relative to the bird’s size, is the largest

of any animal on Earth, and that performs at the

greatest metabolic rate of any bird.

Photographer

Robert Tyrell was able to shoot an unblurred

picture of hummingbirds in flight only after consulting

with the inventor of the strobe light at Massachusetts

Institute of Technology. The solution to capturing

images of the wings was a 1940’s vintage strobe

light that flashes at a 50-millionth of a second,

stopping the wings in flight. There are 339 species

of hummingbirds in the world,

all of them in North and South America (but only

16 in North America). Although tiny, these midgets

of

the bird world are constantly fighting for privacy,

and are combative in the air, scaring away larger,

slower birds. The bee hummingbird in Cuba is the

smallest, weighing no more than a penny, and sometimes

is mistaken

for an insect. The ruby-throated hummingbird found

in Pennsylvania winters in Central Mexico, and

to get there must fly across the Gulf of Mexico—500

miles of open water—in a flight that lasts

26 hours without food. Normally, like other hummingbirds,

it must eat insects or flower nectar several times

a day to survive.

And, finally, they are so exquisitely

colored, their feathers reflecting like mirrors

the colors

of the

sun, that they have a jewel-like appearance.

Long-time Powdermill Scientist Joe Merritt Retires

from Powdermill Nature Reserve

After 25 years as resident director (and since 2003

as research scientist) at Powdermill Nature Reserve

near Ligonier, Pa., Dr. Joseph Merritt has accepted

a position as distinguished professor at the Air

Force Academy in Colorado. After 25 years as resident director (and since 2003

as research scientist) at Powdermill Nature Reserve

near Ligonier, Pa., Dr. Joseph Merritt has accepted

a position as distinguished professor at the Air

Force Academy in Colorado.

Merritt taught small mammal

ecology in the woods of western Pennsylvania. Photo:

Mindy McNaugher

When he became the resident director of Powdermill

in 1979, his mission was to oversee operation

of the station, stimulate ecological scientific

research,

and preserve the museum’s 1,600-acre Field

Station as a prime environment for natural history

research.

During his 25 years, he fostered scientific activities

not only in the nationally respected bird-banding

program but also by making Powdermill a destination

for national

and international conferences and other researchers.

His own specialty in small mammal ecology became

one of the centers of expertise at Powdermill.

Data from

Powdermill is stored on the National Science Foundation’s

Long-Term Ecology Research (LTER) site, a database

about global climate change and long-term

phenomena. As a scientist, Merritt continued to teach

in the evenings as an adjunct professor at Seton

Hill College, and developed programs with Syracuse

University

and Antioch University, as well as the University

of Pittsburgh’s Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology

near Lake Erie. The visibility of ecological science

at Powdermill was significantly raised during his

tenure.

During Merritt’s directorship, with

the support of Ligonier-area benefactors such as

Frank Magee, Thomas

Nimick, and the late Ingrid Rea, Powdermill built

a new Nature Center in 1985, and then expanded

it in

1993 with a classroom building, creating the present

Florence Lockhart Nimick Nature Center. The size

of the Reserve grew to 2,200 acres.

The education

program flourished and expanded as well under Education

Coordinator Theresa Rohall

in recent

years. And popular programs such as Garden

Themes and Bird House Dreams have raised funds for facility

improvements.

As distinguished professor at the

United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs,

Merritt

will continue

his teaching courses in mammalogy and ecology.

He received his doctorate from the University

of Colorado

in 1976,

and he notes that at Colorado Springs his new

office at the Air Force Academy looks out on

Pikes Peak.

Help Carnegie Museum of Natural History by Watching

Great Golf

84 Lumber Golf Classic

Mystic Rock Golf Course at Nemacolin Woodlands Resort.

Thursday, September 23 - Sunday, September 26

Carnegie Museum of Natural History has teamed up with

the PGA Tour and the 84 Lumber Golf Classic to offer general admission tickets

for only $10 per ticket.

This is a 55 percent discount

from the retail price of the ticket ($22). Each ticket

is good for any one

of the four days of the tournament and, most importantly,

the museum receives the full $10 price of every ticket

sold to help with future programming.

Golfers and

golf fans alike can seize this moment to see many

of the world’s top golfers, including

John Daly, and to raise money for Carnegie Museum

of Natural History.

Call 412.622.3288 for more information.

Audubon Society Award goes to Robert C. Leberman

The Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania has given

the 2004 W.E. Clyde Todd Award to Powdermill bird-bander

Robert C. Leberman, citing his “outstanding

effort in furthering the cause of conservation in

Pennsylvania.” The award was named after the

distinguished ornithologist at Carnegie Museum of

Natural History, W.E. Clyde Todd, and has been given

since 1971.

Back to Contents |