Filling in the Blanks: Filling in the Blanks:

The

Teenie Harris Archive

Project Continues

By

Ellen S. Wilson

"This

was the first exhibition that I’ve ever done

that had no labels,” says Louise Lippincott,

curator of Fine Art at Carnegie Museum of Art. “That

was deliberate, because we wanted to encourage people

to come in and fill in the blanks. And they did. We’re

beginning a dialogue instead of a lecture.”

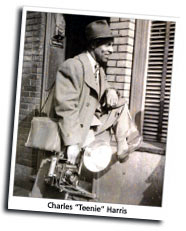

Charles "Teenie" Harris was the principal

photographer for the Pittsburgh Courier from 1936 to

1975. Considered together, his photographs of special

events as well as day-to-day activities constitute

one of the most important records of 20th-century African

American life. The approximately 80,000 photographic

negatives in the Harris archive, however, which Carnegie

Museum of Art acquired in 2001, are largely unidentified.

The ongoing purpose of the Teenie Harris Archive Project

is to gather information about the people, places,

and events shown in the photographs.

“The research and the work on this collection

have to happen out in the community,” says Lippincott. “The

show was a pilot project, an attempt to discover if

displaying the photographs was a useful way to get

information, and it was.” Now, through various

channels, that work is continuing outside the walls

of the museum.

One resource the museum has tapped is the phenomenal

memory and connections of John Brewer of the Trolley

Station Oral History Center in Homewood. Brewer began

his own collection of Teenie Harris photographs about

12 years ago, and is quick to debunk the “One

Shot” myth, a nickname given Harris based on

his apparent ability to take one photograph—one

great photograph—of any scene and move on.

John

Brewer of the Trolley Station Oral History Center in

Homewood collects Teenie Harris photographs and has

been instrumental in helping Carnegie Museum of Art

identify many of the subjects in Harris’ images. John

Brewer of the Trolley Station Oral History Center in

Homewood collects Teenie Harris photographs and has

been instrumental in helping Carnegie Museum of Art

identify many of the subjects in Harris’ images.

Photo: Terry Clark

“He was given that name because of how quick

he was, but if you’ve seen the photographs

I’ve

seen—and I’ve seen thousands—you

realize there were many shots. He should still be

called ‘One

Shot,” because if he was in an environment

with a lot of politicians, a tight spot, he didn’t

have much of an opportunity for a picture. He wasn’t

the Post-Gazette photographer, for example. He couldn’t

ask them to wait a second.”

Brewer first met Lippincott in March 2003 at an exhibition

of Harris’ photographs at Manchester Craftsmen’s

Guild. “They were great photographs,” he

says, “but no one knew what was in them. There

was no real life or history to go with them.” As

an oral historian with deep roots in Pittsburgh’s

African American community—his father was the

first black school principal in the city—Brewer

was able to offer his assistance in identifying some

of the scenes and people shown in the photographs,

and in assembling groups who could shed more light

on the pictures.

One of the groups Brewer has brought to the Trolley

Station to study the photographs is The Girlfriends,

a group of prominent African American women whose

age range, Brewer says, would encompass the relevant

era. “At

their monthly meetings, we set up photos on a table

and just let them go. And they say things like, ‘Oh,

this is my father, he was a judge.’” The

Girlfriends includes such women as Elaine Effort of

KQV, Judge Cynthia Baldwin, and Winifred Tolbert, director

of Community Development for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Of the 80,000 Harris negatives in the Museum of Art’s

collection, 4,000 will eventually be part of the archive

project. Those 4,000 images were selected from work

prints already in existence, and every month up to

300 of them are added to the Museum of Art’s

web site for study. In addition, the University of

Pittsburgh is putting about 500 of Harris’ photographs

on its Historic Pittsburgh site, and more opportunities

are being sought to display Teenie Harris’ photographs

throughout the city.

Girlfriends,

pictured at right at a recent meeting, is a group

of prominent African

American women who

have volunteered to sift through and identify

as many Teenie Harris images as possible during

their

monthly meetings. Several of the members have

found friends and family members among the subjects. Girlfriends,

pictured at right at a recent meeting, is a group

of prominent African

American women who

have volunteered to sift through and identify

as many Teenie Harris images as possible during

their

monthly meetings. Several of the members have

found friends and family members among the subjects.

Photo: Terry Clark

Accessioning the negatives—registering and admitting

them to the Museum of Art’s permanent collection—is

another project altogether. Each one has to be

dusted, written up in a condition report, put into

an archival

sleeve, numbered, and given a descriptive title.

Any information on the image must also be transcribed

and

entered into a database. Scanning the actual images

will come later. For now, gathering information

about existing photographs is paramount.

While the photographs were on display in the Museum

of Art’s Forum Gallery, visitors were invited

to share their knowledge through “memory sheets” in

the gallery or by posting their comments on the museum’s

web site. More than 1,000 memory sheets were gathered

from the two sources by the time the photographs

were taken off display. Now, students of Dr. Laurence

A.

Glasco, a University of Pittsburgh history professor

and a member of the Teenie Harris Advisory Committee,

are following up on some of these memory sheets,

verifying the information provided and trying to

collect even

more.

Since last July, the museum’s own oral historian

for the project, Patricia Pugh Mitchell, has been meeting

with people at libraries, churches, and other gatherings

to elicit memories they may have of the photographs.

A Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Pittsburgh,

Mitchell was coordinator of African American programs

at the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania,

where she wrote Beyond Adversity: Teaching about African

Americans’ Struggle for Equality in Western Pennsylvania,

1750 – 1990. “That research took me out

into the community,” Mitchell explains, giving

her many contacts and sources of information for

the Harris project.

Some older residents are especially helpful in

identifying pictures. “You can put a book of the photographs

in front of them, and they rattle it off,” she

says. Mitchell interviewed Robert Lavelle in his office

on the Hill, where he has been the proprietor of Dwelling

House Savings and Loan for about 50 years. She was

also able to connect with Vivian Hewitt, one of the

first African American librarians hired by Carnegie

Library of Pittsburgh, who now lives in New York. “She

was absolutely fabulous,” Mitchell says.

In addition, Deborah Starling Pollard, the museum’s

community liaison, has been taking slides of the Harris

photographs to community groups and retirement centers

since last June, and often the people she visits see

familiar faces in the pictures. At the Christopher

Smith Senior Highrise in the Hill District, residents

identified a photograph of Chuck Cooper, a Duquesne

University graduate, who was the first black athlete

to enter the National Basketball Association (NBA).

And when Pollard put up a slide of two children with

Easter baskets standing in front of the YMCA on Centre

Avenue, one woman stood up and said, “Those

are my children!”

There is a certain urgency to gathering this information.

Brewer lamented the death last August of Frank

Bolden, a well-known reporter for the Pittsburgh

Courier

in the 1930s and ‘40s who became an unofficial historian

of black Pittsburgh. “Frank took a lot with him,” Brewer

said. “He had so much information. I could say

a word to him, and he’d go on for an hour

if he felt like talking to me. We have to connect

with

our ancestors through living people. We have to

get our people to open up.

“The Museum of Art holds our history in their

hands,” he

continues. “I think they’re doing an

excellent job, and only they can do what is necessary

to preserve

this collection. I appreciate the time made available

for people to see the collection. People need to

understand that the essence of who we are lies

within those pages.

Teenie captured that, sometimes good, sometimes

bad. A lot of stuff happened from 1936 to 1975.

By bringing

it out and allowing us to do what we do, the Museum

of Art has given the general public a much better

appreciation for where they came from, non-African

Americans as

well as African Americans.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

. . . .

Help Document History

Help Carnegie Museum of Art identify Teenie Harris’ images.

Visit the Museum of Art’s website at www.cmoa.org/teenie/info.asp and view up to 500 of Harris’ photographs. Submit

your comments by completing an electronic memory sheet

and become part of the museum's permanent record about

Teenie Harris and his images. Your participation will

enhance the significance of the Teenie Harris Archive

for anyone interested in the history of Black urban

life in the United States in the 20th century.

Back to Contents |