Adventures in Germany

R.J. Gangewere R.J. Gangewere

Dave

Berman finds celebrity—and some 290-million

-year-old fossils—during his 11 years at

work in the Thuringian Forest of central Germany.!

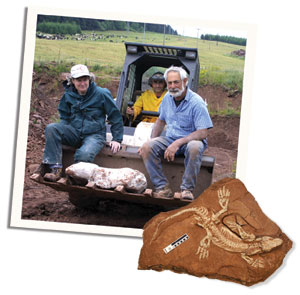

Since 1993, paleontologist David S. Berman has been

digging for fossils of primitive amphibians and reptiles

at the Bromacker Quarry in the Thuringian Forest, which

is near Gotha in central Germany. Until the re-union

of East and West Germany in 1989, this area in East

Germany was off limits to scientists from the West.

But now, after 11 years of work at the site, Berman

and his colleagues have achieved local celebrity status

with the townspeople in the neighboring villages of

Tambach-Dietharz and Georgenthal.

The paleontological team laboring in the quarry with

Berman includes three others: his German host, Thomas

Martens of the Museum der Natur, Gotha; Amy Henrici,

preparator, from Carnegie Museum of Natural History;

and Stuart S. Sumida, from California State University,

San Bernardino. This team has been digging up primitive

amphibians and reptiles from approximately 290 million

years ago, long before the Age of Dinosaurs.

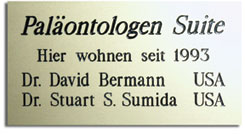

In the Hotel Comtel in Wandersleben (“Wanderer’s

life”), where the American crew stays, their

rooms have been dedicated with plaques: the “Paleontologist’s

Suite” for Berman and Sumida, and the “Preparator’s

Suite” for Henrici. Berman even sleeps in a bed

decorated by the appreciative hotel manager with an

American flag . Downstairs on the hotel restaurant

wall is a cast of two fossils found at the quarry,

and although their scientific name is Seymouria, they

have been given the colloquial name Liebespaar (“loving

couple”) by the German hosts because the specimens

were discovered cheek-to-cheek in the quarry. Also

on the wall is a display of pictures and news clippings

describing the local paleontology, as well as fleshed-out

models of the “loving couple.” In the Hotel Comtel in Wandersleben (“Wanderer’s

life”), where the American crew stays, their

rooms have been dedicated with plaques: the “Paleontologist’s

Suite” for Berman and Sumida, and the “Preparator’s

Suite” for Henrici. Berman even sleeps in a bed

decorated by the appreciative hotel manager with an

American flag . Downstairs on the hotel restaurant

wall is a cast of two fossils found at the quarry,

and although their scientific name is Seymouria, they

have been given the colloquial name Liebespaar (“loving

couple”) by the German hosts because the specimens

were discovered cheek-to-cheek in the quarry. Also

on the wall is a display of pictures and news clippings

describing the local paleontology, as well as fleshed-out

models of the “loving couple.”

Fossils and Bratwurst

The village of Wandersleben has made the scientists

Honorary Citizens, and on a recent fourth of July,

Berman and Sumida received a supply of gifts from the

village, including a box of cigars with their names

on the tubes. Local TV crews have descended yearly

on the site to make 8-10 minute programs about the

fossil dig. Berman recalls that when he first started

work at the quarry, he lived in unbearably cramped

quarters at a youth hostel, and became such an “unhappy

wanderer” that he had to move to the Hotel Comtel.

Now everyone knows when the paleontologists are in

town.

The Burgermeisters of the two nearby villages of Tambach-Dietharz

and Georgenthal each love the idea of having a new

species of fossil named after their towns. This cause

was advanced by the paleontologists when they named

a new species Tambachia trogallas. The name is from

the Greek trogo for “munch” or “nibble,” and

allas, for “sausage,” a reference to the

Thuringian bratwurst that the fossil hunters eat regularly

at the Bromacker Quarry.

Berman is not immune to this distant fame. Back in

his Pittsburgh office, he drinks from a coffee cup

imprinted with a picture of the “loving couple” of

Seymouria. The original fossils are now back in Germany,

after preparation by Amy Henrici, but Carnegie Museum

of Natural History has its own casts of the specimens

in the Vertebrate Paleontology collection.

A Productive Quarry

For more than a decade, Carnegie paleontologists Berman

and Henrici, together with their colleagues, have

been working the highly productive German quarry,

known since the mid-1800s for its “fossil footprints.” The

excavations since 1994 have been funded annually

by the National Geographic Society, with other support

from Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Eudibamous

cursoris

— a running reptile known only from

this site.

To date the site has yielded many superbly preserved

fossils, unique to Europe but also sharing close relationships

to life forms found in the United States. This has

provided the first irrefutable biological evidence

of a pre-continental drift, and a continuous landmass

formed by North America and Europe. Prominent examples

of this commonality are the Seymouria specimens, a

grotesque-looking herbivore (vegetarian) called Diadectes,

and the sail-back reptile Dimetredon. Another example

is the first animal to run on two legs, Eudibamus

cursorius.

The new species underscore the way that scientists

often name new discoveries: after geographic or geologic

features, a unique feature of the anatomy, or sometimes

a unique circumstance, like good local bratwurst.

Finally, as an example of the impulse to “brand” a

community with unique symbolism—such as dinosaurs

in Pittsburgh, or cows in Chicago and codfish in Boston—the

Tambochia trogallas makes a point about the internationalism

of that impulse. While the Burgermeister of Tamboch-Dietharz

enjoys a kind of paleontological status for his town,

his neighbor, the Burgermeister of Georgenthal (who

points out that the Bromacker Quarry is technically

in his district), is still waiting. Georgenthal patiently

hopes for a new species to be discovered —hopefully

a Georgenthal something, in honor of German hospitality.

Corps of Discovery: The Natural History

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Through June 10, 2004

The

species that were first recorded for science

by the Lewis and Clark expedition are displayed

at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The

species that were first recorded for science

by the Lewis and Clark expedition are displayed

at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

In 2003, Pittsburgh celebrated the bicentennial

of the Lewis & Clark expedition’s departure

from the city, and the celebration of that historic

voyage continues in cities across the country until

2006.

The journey

of Lewis and Clark lasted two and a half years—from Meriwether Lewis’s

departure from Pittsburgh in August 1803 to the

final return of the Corps to St. Louis in 1806.

To celebrate that great adventure, Carnegie

Museum of Natural History’s original exhibition,

Corps of Discovery: The Natural History of the

Lewis and Clark Expedition can be seen until June

10, 2004. No other exhibition in the country uses

actual specimens from scientific collections to

give such a unique look at the flora and fauna

that Lewis and Clark encountered.

Garden Themes & Birdhouse Dreams VII Garden Themes & Birdhouse Dreams VII

Powdermill Nature Reserve is already preparing

for a spring 2004 event: the Garden Themes & Birdhouse

Dreams Annual Benefit on May 28, 2004.

Artistic people begin working now on the wonderful

array of one-of-a-kind fanciful birdhouses and

garden–related items that are auctioned off

to benefit the biological field station of Carnegie

Museum of Natural History. The popular event sold

out last year with 300 attendees. Advance reservations

are required, and there are awards and prizes for

the best artistry. The tradition was begun by Patricia

and Harvey Childs, owners of G-Squared Gallery

in Ligonier, and now includes a display of works

(May 19-27) at the Ligonier Library to be auctioned

off.

In 2004, the funds raised will help restore the

five major ponds in the bird banding area at

Powdermill, as well as the “hide” used to view

birds. For more information call 724.593.6105,

email info@birdhousedreams.com,

or visit the website: www.birdhousedreams.com.

Back to Contents |