Machu

Picchu

Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas

By Robert J. Gangewere

In 1911, the lost Inca city of Machu Picchu was discovered

by chance by mountaineer and archaeologist Hiram

Bingham. He was in Peru with three companions to

climb the highest

mountains of the region, and he had been impressed

by Inca ruins two years earlier when he visited

South America on a Yale University tour of ceremonial

sites.

A wealthy explorer, he was fascinated by the

idea of Peru’s legendary “lost city,” which

had disappeared with the Inca civilization in

the 1500s. Hiram

Bingham (1875-1956) came upon Machu Picchu when he

was exploring the valley of the Urubamba River,

about a three-day hike from Cuzco, the ancient capitol

city of the Incas. By chance in 1911, the Peruvian

government had blasted a rough trail through the

river gorges to make a new road that would aid in transporting

products such as cocoa, sugar, and rubber from the

Amazon. Bingham was one of the first to use the road

in his search for lost Inca sites. As a climber,

he

decided at one point to scramble up through the dense

rainforest around him with a companion and an Indian

guide, and he unexpectedly arrived at mid-day at

a high Indian farm 1,000 feet above the plunging river.

Two native farmers working the farm were surprised

to see them, and offered them water and sweet potatoes.

They also told Bingham that there were ancient ruins,

in the common expression, “a little further

on.”

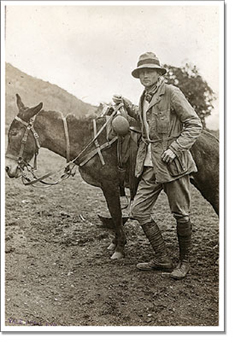

Explorer

Hiram Bingham during a 1912 expedition to Machu Picchu. Explorer

Hiram Bingham during a 1912 expedition to Machu Picchu.

Credit: Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University

With a 10-year old Indian boy as a guide,

Bingham kept on climbing. He suddenly came upon “a

magnificent flight of stone agricultural terraces,

rising 1,000

feet up the mountainside.” He climbed upwards

for an hour more and found himself finally in a

deep forest above these terraces, surrounded by

stone

buildings, including a temple made of granite blocks

that had

been cut with the amazing precision of Inca stonemasons.

Bingham wrote:“ Surprise followed surprise

in bewildering succession. I climbed a marvelous

stairway of granite blocks,

walked along a pampa where the Indians had a

small vegetable

garden, and came to a clearing in which were

two of the finest structures I had ever seen.

Not only

were

there blocks of beautifully grained white granite,

the ashlars [squared blocks] were of Cyclopean

size, some 10 feet in length and higher than

a man. I was

spellbound.” There in the cloud forest of

the Andes mountains, 2,000 feet above the roaring

river below, Bingham

believed

he had stumbled upon the fabled “Lost City

of the Incas.” But was it really that?

The Riddle of Macu Picchu

Machu Picchu was an astonishing 20th century archaeological

discovery, but it was also a puzzle. Modern researchers

such as Yale’s Richard L. Burger and Lucy Salazar

(co-curators of Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery

of the Incas) believe that Machu Picchu was a royal

retreat or country palace, used by the great Inca

Emperor Pachacuti and his guests as a place to relax,

feast, hunt, and engage in ritual activities related

to his divine kingship. In modern American terms,

Burger calls it a “Camp David” for the

Inca Sun God and his followers.

For decades, beginning

with Bingham’s theories,

the mystery of the site has provoked various interpretations:

that it was an ancient military stronghold, or that

it was the last holdout of the Incas against the

invading Conquistadors in the 16th century. Some

believed it

was an isolated religious sanctuary where nuns and

priests worshipped the sun.

Burger and Salazar argue

that it was active for less than 100 years, and

that it was a summer palace for

the Inca elite from Cuzco, the empire's capital.

Situated magnificently in the Peruvian Andes, it

was populated

seasonally by the ruling Inca and several hundred

craftsmen and other servants necessary to carry

on the affairs

of estate and government. Burger and Salazar argue

that it was active for less than 100 years, and

that it was a summer palace for

the Inca elite from Cuzco, the empire's capital.

Situated magnificently in the Peruvian Andes, it

was populated

seasonally by the ruling Inca and several hundred

craftsmen and other servants necessary to carry

on the affairs

of estate and government.

Many of the buildings

in Mach Picchu show

signs of having religious or

spiritual significance.

Salazar believes the

royal estate was built by the first imperial ruler

of the Inca Empire, Pachacuti,

about 1460. Machu Picchu is so close to the

capitol of the empire, Cuzco, that Burger says, "Pachacuti

may well have picked out the site simply because

it was so beautiful. The Inca were connoisseurs

of highland

panoramas, and they had an aesthetic about stonework

and mountain views."

“

Inca” as a word stands for the ruling elite

and their ethnic group. Thus, the Incas, who

ruled an empire

of many different clans and ethnic groups, would

periodically make their presence known by taking

up residence at

a series of royal estates. At Machu Picchu the

population may have been varied in reflecting

the complexity of

the Inca empire. The place was more like a melting

pot of the Inca empire, more like New York than

an isolated rural village in Peru. People living

there

could have come from all over the empire, from

different ethnic groups, and would have spoken

different languages.

But their common purpose for coming together

would have been to serve their emperor, the divine

King. Archaeologists now believe that many of

the buildings

at Machu Picchu show signs of having had religious

and spiritual significance. There are shrines,

royal houses, and a cloister for women. In

Inca tradition,

there were women whose sacred task was serving

the divine King, and who engaged in weaving

and cooking

for the sun. One series of erect monolithic

stones can be interpreted as resting places where the

sun seemed to pause in its course across the

sky. Another

building could have been the place where the

Inca ruler entered to speak directly to the

sun,

and

from which

he returned to tell the people what the sun

had said.

Inca religion was full of natural shrines

with magical importance, places where the sun and

the stars could

be worshipped, and where the ancestors were

venerated. Machu Picchu’s dramatic isolation

high on a granite spine of rock suggests spiritual

meaning. The Inca

were astronomers, and the divine King himself

wore a tunic with rows of complex geometric

motifs, suggesting

the forces of energy that interacted between

heaven and earth.

Experiencing the Exhibition

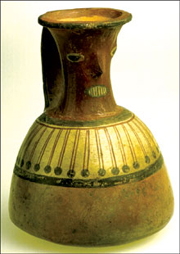

Inca

bottle found at Machu Picchu. Inca

bottle found at Machu Picchu.

Images courtesy of Peabody Museum of Natural History,

Yale University

When Hiram Bingham supervised the Yale-Peruvian excavations

at the site from 1911 to 1915, he excavated hundreds

of objects that tell the story of everyday Inca life,

and he took almost 1,000 photographs of the site

as he worked on it. By agreement with the Peruvian

government, Bingham sent the 1912 materials back

to the collections of the Peabody Museum at Yale.

Featured in the Machu Picchu exhibit are over 300

objects of gold, silver, ceramic, bone, and textile

from the Peabody collection, just part of the total

of 400 objects from various Inca sites. This is the

most complete presentation of the Inca culture ever

organized, containing the finest surviving examples

of Inca art on loan from Peru, Europe, and other

major U.S. collections.

With the exhibit’s

interactive components, visitors “travel” into

the past, first to Machu Picchu with Hiram Bingham

in 1911, and then further back to the 15th century

when Machu Picchu functioned as an Inca royal estate.

There is a panorama of the high altitude cloud forest

of Peru, a walk along a replica of an ancient Inca

road, and a self-guided interactive tour of the Inca

palace complex, including an Inca burial chamber.

Inside the house of the Inca king is a life-size

mannequin

of the king, wearing gold jewelry and an alpaca tunic

specifically reproduced for the exhibit by craftsmen

in Peru.

The exhibit also draws visitors into the

subjects of archaeological interpretation, how

scientists

explored

the riddle of Machu Picchu’s purpose, and why

the site was abandoned.

The Incas—A Rich Civilization that

Disappeared

The Incas were the Romans of the Andean world—efficient

administrators, excellent soldiers, and fine engineers—but

like other South American people they had no written

language. Their tribal power as an austere mountain

clan developed from the 13th century on, and in the

1450s it dramatically increased under emperor Pachacuti

(the Alexander the Great of the Incas) and his son

Tupac Inca who took a small warlike tribe with loose

control over its neighbors and transformed it into

the center of a huge, stable empire. Under Pachacuti

the Incas exercised control over tribes from the

shores of the Pacific to the headwaters of the Amazon,

some

one-third of the continent. The capital city of Cuzco

was built on a monumental scale as a great fortress,

from which the emperor as the Sun God could exercise

complete control.

A bone shawl pick.

Pachacuti

and his son Topa created the amazing network of roads,

fortresses and warehouses

that kept newly

conquered tribes under control. The Inca roads

were marvels of engineering, the finest in the world,

and crossed more difficult terrain than Roman

roads. The “beautiful

road” (Capac-ñan) which runs from

Cuzco to Quito, 1500 miles, with a uniform width

of 25

feet, was built of beautifully dovetailed blocks

of stone.

Rivulets of water ran beside most of the roads,

to quench the thirst of travelers. Pachacuti

and his son Topa created the amazing network of roads,

fortresses and warehouses

that kept newly

conquered tribes under control. The Inca roads

were marvels of engineering, the finest in the world,

and crossed more difficult terrain than Roman

roads. The “beautiful

road” (Capac-ñan) which runs from

Cuzco to Quito, 1500 miles, with a uniform width

of 25

feet, was built of beautifully dovetailed blocks

of stone.

Rivulets of water ran beside most of the roads,

to quench the thirst of travelers.

Just as the practical

Romans derived much of their

rich cultural life from Greek and even Egyptian

predecessors, the Incas adopted many aspects

of their own culture

from earlier and artistically rich Andean civilizations.

The first ancient civilizations emerged on the

coast of Peru about 4,000 years ago. With today’s

knowledge, it is absurd to trace Andean civilization

only back

to the Incas, who for only a brief century or

two were able to fuse into one empire a conglomeration

of already

existing tribes and cultures.

Since no people

in South America had yet invented

writing, the Inca tradition of keeping records

was oral, and

professional bards recited the historical events

of the past, being careful to revise history

by omitting details that predated the coming

of the

Incas. Still,

historians now have the impression that the

pragmatic Inca empire at its zenith was like a caring

and

efficient welfare state, focused on the everyday

needs of its

diverse populations. One example would be the

secret drop-off places in Cuzco, where mothers

could leave

unwanted newborn babies, knowing they would

be cared for by state-run orphanages.

How an Inca society

that was so rich and so well advanced in the arts

of civilization could

suddenly

disappear

from the world scene between the 1530s and

1570s is a critical question. The ruined

Inca buildings,

agricultural

terraces for farming, and amazing roads of

stone remained, but the artifacts and the

detailed records of their

way of life took a long time to be discovered

and analyzed.

“Night fell at noon”: The Spanish

Conquest

The central fact governing the disappearance of evidence

about the historic Incas was the Spanish Conquest that

began in the 1530s. Within a few decades, the daily

objects, ancestral materials, and treasures of Inca

civilization were methodically destroyed or removed

by the Conquistadors. After Francisco Pizarro and his

indiscriminate band of soldiers sacked the Inca capital

of Cuzco in 1533, the other major Inca cities were

soon overcome, and the gold and silver treasures of

the empire were collected, melted, and converted into

bars, and sent back to the treasury in Spain. “Whatever

can be burned, is burned; the rest is broken,” reported

one Spanish chronicler. One Inca observation that survived

was, “Night fell at noon.”

A

17th-century painting depicting the Spanish conquest

of the Incas A

17th-century painting depicting the Spanish conquest

of the Incas

Gold hidden in the national vaults was the economic

foundation of Medieval Europe, and in the 14th and

15th centuries most of it came from the west coast

of Africa. But in the 16th century, South America

presented a new stream of wealth to the mother country,

Spain.

The Conquistadors in the New World not only gathered

up all the precious objects, but they continually

sought something more, the mythic El Dorado—a hoard

of gold at the end of the rainbow—to enrich the

Spanish Crown. The conquest of Montezuma and the Aztecs

in Mexico by Cortez in 1519 had set an example that

a few years later was followed by the Conquistadors

in the Andes. Inca civilization was also ripe for European

exploitation in the early 1500s. A smallpox epidemic

introduced

from Europe had weakened the Andean populations,

killing the last major Inca ruler, and there was a

civil war between two competing contenders for the

throne. It was difficult for Inca clans to unite against

a common enemy.

In addition, the Inca made disastrous

military mistakes. They did not at first retreat

into the mountains

to fight the Spaniards, where they would have had

an advantage, but used clubs and short swords to

fight Conquistadors wearing armor and riding horses

(an animal that had never been seen before). The

Spanish used deadly steel swords, and fired canons

and other firearms. The Incas were slaughtered

by the thousands, and their rulers executed in public.

Soon all the Inca cities had been looted and ruined,

and the ruling class was gone.

Still, there remained a legend, kept alive by the

Spanish chroniclers, of a “lost city” in

the jungle, bypassed by the conquerors, where Inca

cultural materials survived. It was this centuries-old

legend that Hiram Bingham, like many others, was

ready to believe. Machu Picchu, found to be nearly

inaccessible on a mountaintop, seemed to be the

perfect lost city.

Later archaeology and research

in the 20th century

have continued to refine our understanding and

theories about the lost Inca culture. Whether

Richard L. Burger,

director of the Peabody Museum from 1995 through

the end of 2002, and his co-curator Lucy C. Salazar,

have finally solved the mystery of Machu Picchu,

is up to visitors to the exhibit to decide.

Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas was

organized by the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

The exhibit is made possible by grants and support

from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the

National Science Foundation, the Connecticut Humanities

Council, The Heritage Mark Foundation, The William

Bingham Foundation, Yale University and The Peruvian

Connection.

After premiering at Yale University, the

exhibit has started a two-year tour of five Museums:

the Natural

History Museum of Los Angeles County, Carnegie

Museum of Natural History, Denver Museum of Nature

and Science,

and Chicago's Field Museum. One other venue is

yet to be named.

Back to Contents

|