Looking Back

Without the shock and massive grief caused by President

John F. Kennedy's assassination, a lot of events

might not have occurred—or might have had

very different outcomes.

Consider the evidence.

In the late ‘50s and

early ‘60s, we experienced post-war prosperity;

relaxing of a rigid social structure; the birth

of rock ‘n’ roll; the dawn of the media

age; the space race; the Cold War; and the growth

of the civil rights movement.

Kennedy had eased

the Russian threat somewhat; he had hoped to

address civil rights in his second

term.

And he wanted to get us out of Vietnam.

We had yet to view the TV-news horror of that “conflict,” which

prompted protests by draft-fearing youth who, for

the first time, challenged authority and the status

quo.“Hell no, we won’t go” morphed

into a huge generation gap fueled by the notions

of free love, rock ‘n’ roll and the credo, “Turn

on, tune in, drop out.”

But during Kennedy’s reign, we still accepted

the presidency as a sacrosanct position and respected

those who held it. “When the American government

told you something was right, you believed it,” says

Dr. Cyril Wecht, Allegheny County coroner and

nationally acclaimed forensic science expert.

That was before

Lyndon Johnson’s policies produced revelations

that not all wars are justified and presidents

do lie; before Richard Nixon irrevocably turned

us into

cynics and caused the rise of investigative journalism.

On

the 40th anniversary of Kennedy’s death,

we find ourselves looking back to examine why

and how that event had such a monumental effect.

The Kennedys

The Kennedys

To those who believe in the forces of Good and Evil,

the idea of a curse sitting on the heads of Joseph

P. Kennedy’s male descendants is totally

believable.

Consider the evidence. Each one of the patriarch’s

sons suffered a cruel fate: His namesake was killed

in World War II; both John and Bobby were felled

by assassins’ bullets; Teddy nearly died in

a 1964 plane crash, then was involved in a scandal

that kept him from the White House. Some of their

progeny have met equally gruesome fates, including

the last Kennedy presidential prospect, John F. Kennedy

Jr., who piloted his plane to a watery grave. President

Kennedy’s second son, Patrick, died two days

after his birth—just a few months before his

father was buried.

Popular culture helps to perpetuate

the Kennedy Curse. For example, a song by New Zealand

singer Shona Laing

zeroes in on the Kennedy family’s suffering

with a sharpshooter’s accuracy. In (Glad I’m)

Not A Kennedy, the chorus repeats: “Wearing

the fame like a loaded gun/Tied up with a rosary/I’m

glad I’m not a Kennedy.”

“Wearing the fame like a loaded gun.” That

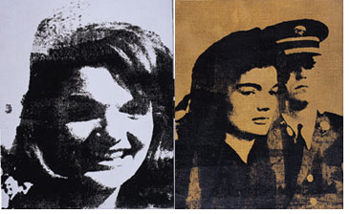

was the concept Andy Warhol sought to convey when

he

began his artistic obsession with JFK’s

stoic widow, who not only represented the pinnacle

of

beauty and fame, but who also knew how to manipulate

the

media. Warhol craved similar fame and control,

and may have turned to her for lessons.

Yet even

when Warhol achieved notoriety himself, he

still remained awed by Jackie and what he

regarded as her skill at manipulating the public’s

perception of her. Though it is legitimate to

question whether

Jackie was still performing a role years after

the assassination, there is no doubt that Warhol

reveled

in playing one himself—and in his ability

to cultivate his own persona.

“He was a creation from head to toe,” says The

Andy Warhol Museum Director Thomas Sokolowski. “He

was an artwork. She didn’t go that far.”

Creating Camelot

Already larger than life in the eyes of many adoring

Americans, Jack Kennedy became a superhero as soon

as he died. His wife became a grieving Madonna

figure, a dignified, yet heartrending symbol of

America's loss—of both its president and

its innocence. The public willingly accepted the

idea that her husband's 1,000 days in office took

place in an idyllic time that “for one brief

shining moment … was known as Camelot.”

Jackie

introduced the notion of Camelot in a post-assassination

interview she gave to friend Theodore H. White

for Life magazine. White ran with it, and unwittingly

helped spin the fairytale he later came to regard

as exactly that.

Warhol ran with it, too, despite his expressed

disdain for the inescapable coverage of the events

surrounding

Kennedy’s death. While Warhol hated the idea

that the first major news event played out on TV

came with the implication that everyone should have

media-directed feelings of sadness and grief, his

assassination silkscreens make it clear that he did

experience those emotions—and actually helped

perpetuate them.

“Warhol was always push-pull,” says

Sokolowski. “There

were often dichotomies between what he said and

what he did.”

With his trademark use of repeated images, Warhol

immortalized several frozen-in-time moments

from before and after the assassination in Jackie

(the Week that Was), and Sixteen Jackies. First she

is shown with a smile and her cocked pillbox

hat, then

she’s a stunned wife, and finally, a set-lipped

mourner. Warhol also turned those images into

separate pieces, and created his now-familiar

portrait of

Jackie as a lovely-looking first lady. A few

years later, he produced his powerful Flash,

a series of

silkscreens depicting a grinning president, his

glamorous wife, a presidential seal with bullet

holes through

it, an ad for an Italian carbine rifle, and other

symbolic representations of that tragedy.

With his trademark use of repeated images, Warhol

immortalized several frozen-in-time moments

from before and after the assassination in Jackie

(the Week that Was), and Sixteen Jackies. First she

is shown with a smile and her cocked pillbox

hat, then

she’s a stunned wife, and finally, a set-lipped

mourner. Warhol also turned those images into

separate pieces, and created his now-familiar

portrait of

Jackie as a lovely-looking first lady. A few

years later, he produced his powerful Flash,

a series of

silkscreens depicting a grinning president, his

glamorous wife, a presidential seal with bullet

holes through

it, an ad for an Italian carbine rifle, and other

symbolic representations of that tragedy.

Ruth Ann Rugg, director of interpretation at

Dallas’ Sixth

Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, a collaborator

with The Andy Warhol Museum on the exhibition,

notes: “Warhol

of all people was fascinated with publicity,

with public attention. … He was, I think,

really aware of how much this one event had

captured the

attention of the whole nation.”

The constant

replay of assassination footage also reinforced

Warhol’s own use of repetition.

And in keeping with Warhol’s catholic

background, Rugg says, “He more or less

did elevate Jackie to the status of a saint.”

As Sokolowski notes: “Had (Kennedy) not been

killed, she would only have been the pretty first

lady.”

The Mystery

At first, the public believed what it was told: that

Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. But once the distrust

set in, people started questioning the validity

of that explanation.

Stephen Fagin, oral history coordinator at the Dealey

Plaza museum, suggests, “After Watergate, people

thought, ‘If they lied to us about this, did

they lie to us about the Kennedy assassination?’

“It just becomes this big question mark,” Fagin

says. “The

mystery endures because it is a mystery.”

Wecht, who discovered the lack

of forensic record-keeping in the Kennedy case says we’re also still

saddened by the loss of a young, dashing, Pulitzer Prize-winning, World War

II hero with all that unfulfilled promise. Combined

with our disbelief in our government and continuing questions about the evidence

he says, “You have a case that will not die.”

Wecht, a proponent

of the conspiracy theory, also served as a consultant on Oliver Stone’s

1991 feature film, JFK, which exposed a new generation of Americans to

the events surrounding Kennedy’s life and assassination. After the

movie was released, says Fagin, “From that point on, the assassination

was a current event.”

Every day, Fagin says, people come to the plaza, “And

they mill around and look, as if somewhere, out there, the answer is

still there.”

As if he were quoting a script

from The X-Files, Fagin adds, “The more

you look, the more confusing it becomes.” n