Strangely Familiar: Design and Everyday Life

By Ellen S. Wilson

A chocolate

ruler to measure greed. A house that can be folded

up to fit in your pocket. Garments that transform

into an armchair, a kite, or a tent. These are

just a few of the objects featured in Strangely

Familiar: Design and Everyday Life, an exhibition

organized by Walker Art Center, Minneapolis,

that considers the role designers play in cultural

sensibilities.

|

Over the past decade, the increasing number

of designed objects available to the consumer

has created a greater awareness of all aspects

of design, from architecture to furniture, fashion,

graphics, and products for the home. How we live

and travel and how we function at home and at

work are all influenced by this new culture of

design, and the three-dozen pieces featured in

this exhibition ask fundamental questions about

how we interact with the built environment.

A multidisciplinary exhibition drawn from international

sources, the show has four themes: extraordinary

objects and spaces that refer to and transform

common objects; multifunctional objects that

change both shape and use; portable structures;

and objects that force users to reconsider their

basic relationship to the product, leading to

new uses and expectations.

“ People are very conscious these days

of new communication technologies, of the huge

amount of intelligence that can fit in a small

chip,” explains Raymund Ryan, curator of

architecture at Heinz Architectural Center. “At

the same time, there is a reappraisal of ordinary

things, and the notion of the ordinary is different

now.”

For example, the London-based designers Anthony

Dunne + Fiona Raby’s Placebo Project places

electronic objects such as a global satellite

positioning device into household furniture. “At

first the furniture looks very banal,” says

Ryan. “They deliberately photograph their

pieces in very ordinary houses and backgrounds,

as if to say that their work is not about high

design. Anybody can use it.”

The do create collection—developed

by Droog Design in collaboration with the Amsterdam

advertising agency KesselsKramer —demands

that the consumer interact with the product as

a way of customizing it. do break is

a ceramic vase with a coating that allows it

to crack but not splinter; do swing is

a light fixture that hopefully supports the weight

of even corpulent partygoers. “You make

it your own,” says Ryan. “It’s

not some pure thing, the traditionally precious

design object on its pedestal.”

Architectural elements are a key aspect of the

exhibition, with many young designers reconsidering

the potential of the shipping container. “High

Modernists before World War II and then again

in the 1960s also experimented with pod architecture,

but what might be different now is that the projects

are more realistic and less utopian,” says

Ryan. Japanese architect Shigeru Ban’s Paper

Loghouse was developed after the 1995 earthquake

in Kobe, Japan, as a response to the sudden need

for quick, practical housing. The house sits

on a base of Kirin beer crates, the walls are

cardboard tubes, and the roof is canvas.

“ These designers are less interested

in inventing a new pod per se, but in seeing

what can be done with what already exists, hence

the name Strangely Familiar,” adds

Ryan.

The exhibition runs concurrently with Very

Familiar, a celebration of the first 50

years of the Department of Decorative Arts

at Carnegie Museum of Art, and a study of the

philosophy and themes that run through

the collection. |

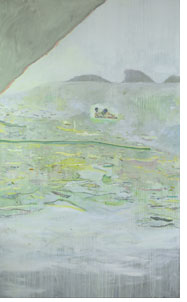

Recent Acquisition:

Driftwood, 2001-2002, by Peter Doig  Peter

Doig, British, 1959, Peter

Doig, British, 1959,

Driftwood, 2001-2002, oil on canvas,

Carnegie Museum of Art, The Henry Hillman Fund.

Peter

Doig’s landscapes and nature scenes are

painted from photographs, both his own and those

found

in newspapers, postcards, record covers, movie

stills, and other sources. Born in Scotland in

1959, Doig grew up in Canada and moved to London

for further studies, receiving his Masters in

Art from the Chelsea School of Art in London

in 1990.

For five years he was a trustee of the Tate Gallery

in London, and in 2002 he moved with his family

to Trinidad. “

This picture is unusual in the artist's oeuvre

by virtue of its shape,” explains Curator

of Contemporary Art Laura Hoptman. “Although

Doig has painted very large landscapes for

the past 10 years, he rarely

has painted a vertical composition like this one.”

Doig

often works in a series, using the same motif

numerous times, sometimes referring to the images

as flashbacks or memories. Carnegie Museum of

Art

received

as a gift a large, finished painting on paper, also titled Driftwood, which

is similar in design. “According to the

artist,” says

Hoptman, “the

work on paper was begun before the painting, but completed after the painting

was finished. Thus, it served both as a study and an addendum to the larger

work.”

Considered

one of Britain’s

leading artists, Doig was nominated for the

prestigious Turner prize in 1994. While many of

his landscapes

to date have been

reminiscent of his upbringing in Canada, his recent work is beginning to

reflect his current home in the Caribbean.

Impressionist

Prints Celebrate Light, Life, and Friendship

Childe Hassam: Prints and Drawings from the Collection

Frederick

Childe Hassam always rejected the stylistic label

of “Impressionist.” Hassam (1859–1935)

began his career in Boston as a wood engraver

and illustrator, and started painting in the

Impressionist style after an inspiring trip to

Paris between 1887 and 1889. He turned to printmaking

in 1915, first etching and then lithography,

eventually producing some 375 etchings and 42

lithographs. Frederick

Childe Hassam always rejected the stylistic label

of “Impressionist.” Hassam (1859–1935)

began his career in Boston as a wood engraver

and illustrator, and started painting in the

Impressionist style after an inspiring trip to

Paris between 1887 and 1889. He turned to printmaking

in 1915, first etching and then lithography,

eventually producing some 375 etchings and 42

lithographs.

Known mostly for his landscapes,

Hassam’s

abiding interest is capturing the effects of

light and air

in the natural environment. He and his wife, Maude,

moved to New York City in 1889, and summered in New

England or in East Hampton, where he found inspiration

for much of his work. He also did a series of paintings

and lithographs of patriotic flag displays in New

York during World War I, as well as scenes of lively

street life or skyline views. His natural affinity

for graphic arts may be seen in his explorations

of color and pictorial structure.

“

These drawings lend insight into an essential

truth about Hassam’s picture-making,” explains

Linda Batis, associate curator of Fine Arts. “He

drew and painted what he saw before him.”

Despite

his resistance to the label, Hassam became

the best known American painter in the Impressionist

style. He enjoyed a long friendship with John

Beatty, director of Fine Arts at Carnegie Museum

of Art

from 1896 to 1922, and exhibited more than

90

paintings at the Carnegie Internationals, the

museum’s

annual exhibition of contemporary art. He served

on the exhibition’s award jury in 1903

and 1904, and again in 1910, during which he

was given

a solo exhibition. He also served as an informal

advisor to Beatty on purchases of work by other

artists.

In 1900, Carnegie Museum of Art became

the first American museum to acquire one

of Hassam’s

paintings with the purchase of Fifth Avenue

in Winter. In 1907, Beatty purchased 30 drawings

directly from

the artist, one of the largest such groups

in any museum collection and—according

to the artist—some

of his best. The etchings and lithographs on

view in this exhibition are from a group of

60 prints

donated by Hassam’s widow in recognition

of the close relationship between the artist

and Carnegie

Museum of Art.

Back to Contents |