Space Exploration

in 1803:

The Lewis and Clark Expedition

By Robert J. Gangewere

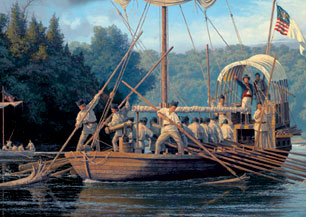

Lewis

and Clark: The Departure from the Wood River

Encampment,

May 14, 1804, a painting by Gary R. Lucy. The expedition

begins its journey up the untamed Missouri River after

wintering

on the United States side of the Mississippi. Lewis

and Clark: The Departure from the Wood River

Encampment,

May 14, 1804, a painting by Gary R. Lucy. The expedition

begins its journey up the untamed Missouri River after

wintering

on the United States side of the Mississippi.

The “Corps of Discovery” dispatched

by President Thomas Jefferson in 1803 was the first

scientific expedition ever undertaken by the United

States—the

prototype of all national scientific enterprises,

including today’s missions into outer

space. Not surprisingly, the expedition had

its critics,

and Jefferson had

to persuade Congress to appropriate $2,500

for the adventure.

He helped select the launch point: Pittsburgh. This year is the bicentennial of that early exploration

into uncharted space, and Pittsburgh’s

special day in the national calendar of celebration

is

August 31, the very day that Captain Meriwether

Lewis put

his Pittsburgh-built keelboat into the Monongahela

River

and directed his crew to start rowing west down

the Ohio towards the Pacific. The city’s celebration is being spearheaded

by the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania,

which

will have a special exhibit (including a replica

of the Pittsburgh-built keelboat), and has

collaborated with

other groups to stage a river flotilla and

celebrations at the Pittsburgh Point. Carnegie Museum

of Natural

History is installing a year-long Lewis and

Clark exhibit,

and

Carnegie Science Center is featuring the expedition

at the Rangos Ominmax Theater and in a skyshow

at Henry Buhl, Jr. Planetarium and Observatory. 1803:Politics and a New Frontier

That summer in Pittsburgh,

Lewis sup-ervised the building of the keelboat he had

specially

designed, and collected the tons of supplies

and trade goods to outfit the journey. Pittsburgh

was the Gateway to

the West, but more than

a thousand miles away near St. Louis, where

the Missouri emptied into the Mississippi,

the unknown

frontier really

began. After wintering across from St. Louis

in 1803-04, on the American side of the Mississippi,

the Corps of

Discovery started the second leg of its journey

by rowing up the Missouri on May 14. The years

1803-04 were a turning point in American history,

full of geopolitical pressure,

commercial

dreams, and

scientific promise. The British in Canada

had been moving to outflank the United

States by

exploring

and claiming

vast tracts of land west of the Mississippi.

In France, Napoleon countered the expanding

British Empire by

suddenly selling the “Louisiana Territory” to

the United States. The money helped him

finance another war

against Great Britain, and when the sale

was completed, Napoleon boasted, “I

have just given England a rival that will

sooner or later humble her pride.” Jefferson,

elected the third president in 1801, quickly

borrowed $15 million,

a sum

nearly

twice the American

budget, to buy all 820,000 acres from France.

With the stroke of his pen he more than

doubled the

size of his

country at three cents an acre. But few

Americans knew anything about the land

he bought, and

his critics called it “shameful gross

speculation,” and complained

that the United States had no more right

to this land than to “land in the

moon.” The Louisiana

Purchase added a political justification

for the Lewis and Clark expedition. Jefferson,

like others, believed there was a Northwest

Passage to discover—some river or

a series of rivers connected by a short

portage over the mountains —-that

would take explorers to the Pacific, and

make possible direct Amer-ican trade with

the Orient. He wanted to

expand national commerce, open up the fur

trade, and develop new frontier settlements.

And he was passionate

about scientific discovery—so much

so that he had tried several times in the

previous 20 years

to

get scientists

to explore the Pacific Northwest, but had

always failed. Jefferson appointed his personal

secretary and fellow Virginian, Meriwether

Lewis, to

be Captain of the expedition,

and he had Lewis

take

crash courses in science in Philadelphia,

the American center

of science. Lewis was tutored by the nation’s

best botanists, astronomers, anatomists,

and physicians. He

learned

to describe and preserve botanical specimens,

to analyze anatomy, to navigate by the

stars, to determine latitude

and longitude, to identify fossils, and

perform basic medical procedures, such

as bloodletting. The Pittsburgh Launch

Lewis had designed a modified

keelboat as the vehicle for

his mission, and he oversaw its construction,

probably at

the Greenough boatyard near the present

Liberty Bridge. Unfortunately, the boat

builder was

a drunkard and a

liar, involved in disputes with his workers,

and the construction took a month and a

half beyond the scheduled

time of departure. Lewis went through an

agony of frustration as the Ohio River

dried up and

became unnavigable in

August, seemingly dooming his mission.

Local rivermen complained that the river

was lower

than anyone could

remember, and every day Lewis pleaded or

threatened the boat builder to complete

the job.

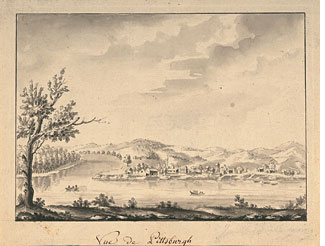

View of Pittsburgh in 1797, by Joseph Warin.

The keelboat was built on the banks of the

Monongahela six years later. Courtesy of The

New York Public Library. View of Pittsburgh in 1797, by Joseph Warin.

The keelboat was built on the banks of the

Monongahela six years later. Courtesy of The

New York Public Library.

To lighten the keelboat, Lewis

sent a wagonload of goods ahead to Wheeling.

He also bought

a flat-bottomed rowboat

with a sail—a pirogue—to carry

some of the goods. When the keelboat finally

slid into

the

water

at 7 a.m. on August 31st,

it was loaded quickly and the explorers

left Pittsburgh by 10 a.m. The first day

the expedition

made 10 miles,

after unpacking the keelboat three times

to haul it over sandbars.

At the first

stop, on Brunot’s island three

miles downriver, Lewis took time to demonstrate

his new air-gun,

a pneumatic rifle made in Philadelphia,

that fired without smoke or noise. While passing

this amazing

gun around,

it accidentally went off, wounding a woman

slightly in the temple. The explorers never

passed the loaded

gun

around again, and on the rest of the journey

they used it to amaze the Indians. In Pittsburgh

Lewis also bought a large dog, recording that

it was “of the Newfoundland breed very

active strong and docile.” He called

it “Seaman” and

it became his constant companion on water

and land. Seaman caught squirrels and other

animals (one

time he caught

a swimming antelope),

and he guarded the camp at night. Seaman’s

barking warned off prowling grizzly bears

in the western mountains.

Lewis refused to trade him to the Indians

who wanted him, and when some thieves stole

him, Lewis had

them tracked until they released the dog. A True Voyage of Discovery

Mary

Dawson, curator emeritus of Vertebrate Paleontology

at Carnegie Museum of Natural

History, points

out that, scientifically, this was a true “voyage

of discovery.” She

adds, “Although many animals and

plants in the wild had been seen by Native

Americans and

French explorers,

the small scientific community in the United

States had never attempted to collect and

describe them.

A new chapter

of natural history science was opened by

this expedition, and there were many consequences

from the notes

and specimens that Lewis and Clark sent

back. Within a decade there

were many discoveries of new species.”  Dawson

heads the museum’s preparation of

the bicentennial exhibit Natural History

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition,

1804-1806: The Corps of Discovery. This

exhibit presents ex-amples from the museum’s

collections of the species first noted

by Lewis and Clark. They described

in their journals 178 plants and 122 animals

not previously recorded, including animals

such as the grizzly bear,

antelope, the mule-deer, the kit-fox, coyote,

prairie dog, and mountain “beaver” of

the Pacific Northwest. Two of the new species

of birds identified

were “Lewis’ Woodpecker” (Melanerpes

lewis) and “Clark’s Nut-cracker” (Nucifraga

columbiana), in addition to the Bald Eagle,

California Condor, and the now extinct

Passenger Pigeon. Dawson

heads the museum’s preparation of

the bicentennial exhibit Natural History

of the Lewis and Clark Expedition,

1804-1806: The Corps of Discovery. This

exhibit presents ex-amples from the museum’s

collections of the species first noted

by Lewis and Clark. They described

in their journals 178 plants and 122 animals

not previously recorded, including animals

such as the grizzly bear,

antelope, the mule-deer, the kit-fox, coyote,

prairie dog, and mountain “beaver” of

the Pacific Northwest. Two of the new species

of birds identified

were “Lewis’ Woodpecker” (Melanerpes

lewis) and “Clark’s Nut-cracker” (Nucifraga

columbiana), in addition to the Bald Eagle,

California Condor, and the now extinct

Passenger Pigeon.

Among the trees recorded

were the ponderosa pine and the cottonwood,

and plants included

the bitterroot,

common arrowhead, and prickly pear cactus. “The

prickly pear is now in full blume and forms

one of the beauties

as well as the greatest pests of the plains,” wrote

Lewis. Its needles tortured men and

animals alike. On one frustrating day,

Lewis recorded, “It

now seemed to me that all the beasts of

the neighborhood had made league to destroy

me—I thought it

might be a dream, but the prickly pears

which pierced my

feet severely once in a while, particularly

after it grew

dark, convinced me I was really awake,

and that it was necessary to make the rest

of my way to

camp.” Insects were also a problem: “Our

trio of pests still invade and obstruct

us on all occasions, these

are Muskquetoes, eye gnats, and prickly

pears, equal to any three curses that ever

poor Egypt labored under,

except the Mohametant yoke.” The

wasps (Vespa diabolica) “are

fierce and sting very severely, so we found

them very troublesome in frightening our

horses as we

passed

the mountains.” The explorers also

collected fossils and rock specimens. Carnegie

Museum of Natural

History’s Section

of Invertebrate Paleontology is planning

a virtual tour

on its web site to illustrate key fossil

collecting sites, and important geologic

exposures along the

trail of the

Corps of Discovery. By the time they reached

North Dakota and built Fort Mandan, Lewis

and Clark had

some 40 men

under their

command, and traveled in the big keelboat

with two canoes and

two pirogues. But after wintering there

in 1804-05, they returned some men back

to St.

Louis with

the keelboat, which they filled with natural

specimens,

maps, and

reports

of their travels. From North Dakota a smaller

party headed to the Pacific over the mountains,

walking,

riding, paddling

canoes and boats—whatever would take

them to the ocean. A Report that Sparked Immigration

Jefferson, anxious

about the success of the mission, had not heard

directly from

his Corps

for

a long time

when he finally received back in Washington

the evidence of their travels and the first

collected specimens.

The first report, some 45,000 words, summarized

meetings with 72 native tribes, assessments

of trading and settlement

possibilities, and included four wooden boxes

and a large trunk full of specimens such

as skins, skeletons,

mineral samples, and Indian corn. There were

also three cages containing live animals:

a prairie dog, four

magpies, and a grouse. The boxes had traveled

from St. Louis down the Mississippi to New

Orleans, and

were shipped around Florida and up the coast

to Washington.

A sketch of the White Salmon A sketch of the White Salmon

Trout (Sturgeon acipinser)

in Clark’s journals.

Jefferson was so proud of the discoveries of the

expedition that he put up at his home in Monticello

a display

wall of specimens he had received.

He planted the Indian corn in his garden, hung

the elk antlers in his foyer, and sent the surviving

animals —a

magpie and prairie dog—to

a natural science museum in Philadelphia’s

Independence Hall.

He also ordered the first report

published, along

with William Clark’s maps. The result was

that soon, all across America, Britain and Europe,

adventurers,

entrepreneurs, and scientists began to make plans

to

go west. The second report, written in 1806, put

an end to the dream of a Northwest Passage, but

outlined

Lewis’s

hopes for American expansion into the West, and

for a great fur trade with China. It confirmed

the idea

of an America extending from sea to sea, which

was played out in the 19th century as America’s “Manifest

Destiny,” long after Lewis’s own

death in 1809. The

high adventure of the Lewis and Clark expedition

still captures the public imagination after

200 years, with its compelling and detailed record

of the American

West as wild, awesome, and pristinely beautiful.

Back to Contents |