Documenting

Our Past:

The Teenie Harris Archive Project

By Ellen S. Wilson

Charles "Teenie" Harris

The public will have

an opportunity to see the photographs—and

make a contribution to the historical record they represent—when

part one of the Teenie Harris Archive Project opens. “Our

goal is to show as many unpublished photographs as

we can, and invite the public in to tell us what they

are about, to help identify the people, places, and

events they represent, and to tell us what memories

the photographs trigger,” explains Louise Lippincott,

the museum’s curator of fine arts. In 2001, Carnegie

Museum of Art acquired the Harris archive after the

Harris family’s successful

suit against a private dealer to gain control of

the photographic negatives. The museum had acquired

4,500 prints in

1997, but Harris, who never threw a negative away,

took approximately 100,000 photographs during his

career. The recent acquisition contains more than

80,000 of

those negatives, many of which are set in Pittsburgh’s

Hill District. “The community has the information

we need to catalogue the photographs,” says

Lippincott. “The

best way for us to get the information is to make

the photographs available, and to listen to what

people

have to tell us.”

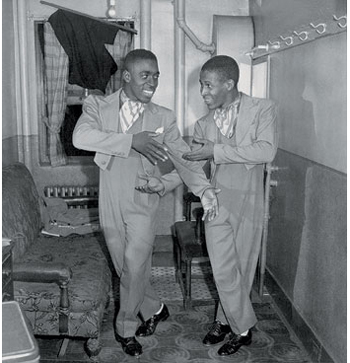

The

Performers The

Performers

The museum is working with a Teenie Harris

Advisory Committee

on the enormous

task of identifying the

photographs. To that end, work prints (prints

not made by Harris)

and hundreds of photocopies of photographs in

binders will be on view so visitors can see what the

pictures

are and share that information with the museum.

This is a pilot project, Lippincott explains, with

different

strategies in place to capture the information. “We

want to see what works, and how much information

we can get. It will have a huge influence on

how we manage

the collection.” “

I think we’ll learn a lot,” says

Glasco, who is a member of the advisory committee.

Glasco recounts

a recent talk he gave in Baldwin on the Harris

archive, “and

it was surprising how many people, white as well

as black, lived on the Hill and had known Harris

or their

family had known him. It was clear that the photos

do evoke memories and people do have stories

to tell.”

Glasco says the information will

not only provide a major contribution to scholarship,

but it will

also

help bring the community together. “People

have forgotten the glory days of the Hill,” he

says. “The Hill was a highly integrated

neighborhood. Until 1930, it was mostly White,

with many Italians

and Jews, but also Chinese, Syrians, Lebanese,

Greeks, Irish, Poles, Germans. There were all

sorts of ethnic

groups there.

“If it is made clear to

them, these people will come and help contribute

to the fuller history of the Hill, which we’ve

forgotten. These pictures will

provide a renewed sense of place.” Harris,

with no formal training, began his career as

a freelance photographer, and then

worked

as principal photographer for the Pittsburgh

Courier from 1936

through

the mid-1970s. At that time, the Courier was

one of the country’s most influential

black newspapers with four national editions,

as well as editions for

Africa, the West Indies, and the Philippines.

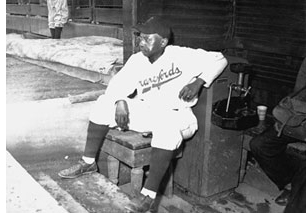

Crawfords' Crawfords'

Baseball Player

It was Mayor David L. Lawrence who first gave

Harris the nickname “One Shot” for

his tendency to snap only one shot of a scene

and then move on.

A true photojournalist, more interested in

the stories the pictures told than technical

prowess, he nevertheless

had an instinctive eye for a picture and an

innate ability to take it at just the right

time. As his son Charles A. Harris, wrote, “Dad

believed in brevity. He felt that more people

should concentrate on giving shorter answers

and writing shorter speeches. When Dad answered a question

he was succinct. You knew exactly where he stood; there

would be no sugar coating in his answers. This trait

carried over into his work.”

“He was a wonderful photographer,” says Lippincott. “Putting

aside

subject matter, the way he composed a scene,

the way he represented people, make these images

wonderful in their own right.”

Subject

matter, however, is part of what makes these

pictures so valuable. “The more famous

black photographers were mainly studio photographers,” explains

Glasco. “They didn’t take that

many photographs out on the street, and they

had a more middle class

audience. Harris took photographs of the middle

class and blue collar—not just famous

people, but ordinary subjects. For example,

he would shoot the baseball

players, but also the fans in the stadium.

. . . He was interested in capturing just people.”

Back to Contents

Recent Acquisition:

An Inner Dialog with Frida Kahlo

By Ellen S. Wilson

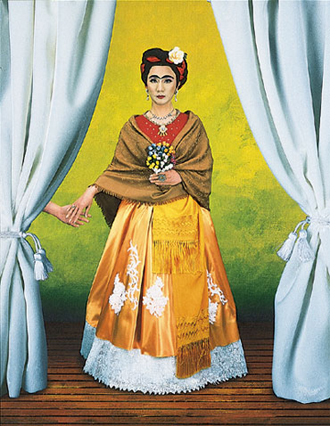

An

Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo (Gift 2), 2001, by

Yasumasu Morimura, c-print; ed. 6/10. Gift of Pamela

Z. Bryan. An

Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo (Gift 2), 2001, by

Yasumasu Morimura, c-print; ed. 6/10. Gift of Pamela

Z. Bryan.

With the purchase of An Inner Dialog with Frida

Kahlo,

the Museum of Art gains a work by one of the

most important voices of the 1980s in photography

in Japan,

says curator

of contemporary art Laura Hoptman. Yasumasu Morimura,

born in 1951, uses digital techniques to interpose

himself into famous works of art or famous figures

in cinema. Liza Minelli, Marilyn Monroe, even

the Mona Lisa herself, are all transformed by Morimura

into

new images that can be both disturbing and amusing.

Inspired by high art as well as the commercial,

Morimura piles artifice onto artifice, drawing

on the work of Cindy Sherman and Mariko

Mori, among others. In the series “An Inner

Dialogue with Frida Kahlo,” Morimura

assumes the persona of the artist Frida Kahlo

(1907-1954), a Mexican painter well known for

striking self-portraits that portrayed the love,

pain, sickness,

and joy of

her tumultuous life. This practice of replacing

the subject’s face with his own is conceptually

rooted in both the Japanese Kabuki theater tradition,

where

male actors play female parts, and in postmodern

appropriation, where artists borrow imagery from

diverse sources to

comment

upon the power of images themselves. Morimura’s

near-perfect photographic copy of Kahlo’s

painting extends the transformation further swapping

elements from her original composition

for those of Japanese origin, such as the hana

kanzashi, Japanese flowered hairpins that he

has substituted

for the flowers in Kahlo’s hair. The resulting

photographic work allows Morimura to pay subversive

homage to Kahlo, whose own life and art parallel

the “beautiful

commotion” that Morimura seeks in his own

work.

Back to Contents |