|

†

Meet Museum Director Bill DeWalt†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

By R. Jay Gangewere

The new director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Bill

DeWalt, Ph.D., has had a distinguished career at the University of Pittsburgh

since 1993 as an anthropologist and director for its Center for Latin

American Studies.

"Our research was a global one, but we couldn't be

more pleased that it ended right here in Pittsburgh, with Bill DeWalt,"

said Dr. Ellsworth H. Brown, president of Carnegie Museums of

Pittsburgh.† "Bill has it

all--administrative experience, success as a fundraiser, a strong commitment

to scientific research and discovery, and the enthusiasm and creativity that

are so crucial to advancing the mission of this wonderful institution."

As director of the University of Pittsburgh's Center for

Latin American Studies since 1993, DeWalt has increased the Center's

endowment from $700,000 to more than $6 million. He expanded the Center's

K-12 outreach program, established a new graduate certificate program in

Latin American Social and Public Policy, built strong relationships with

Latin American embassies, international conservation programs, and with the

private and public sectors, including Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.†

Born in Shamokin, Pennsylvania, and raised in Bridgeport,

Connecticut, DeWalt† earned his BA in

Sociology and Anthropology from the University of Connecticut, and in 1977

began a 15-year academic career at the University of Kentucky, where he was

chair of the department of Anthropology and director of the Latin American

Studies program, before moving to Pittsburgh.†† DeWalt remains a Distinguished Service Professor at the

university, which enables him to approach universities as a peer when

exploring new relationships between academia and the museums.

When asked what philosophy should guide a natural history

museum, De Walt says:† "I think

it has two main scientific charters: ecology and evolution.† Weíre here to help people understand

biodiversity and cultural diversity as they are revealed throughout history

and ongoing scientific research.† When

someone visits a natural history museum,†

they should walk away with a better understanding of the diversity of

our natural and human resources."

He is committed to preserving the museum's

collections.† "Every educational

and scientific institution needs a strong library, and thatís how I view the

museumís collections: as a valuable library of scientific research and

knowledge that is the heart and soul of the institution."

Regarding the role of technology, DeWalt says, "It

makes the collections more accessible to a larger public.† With the help of technology, we can, in

effect, turn the museum inside out and really let the world see whatís

inside.† Thatís the greatest purpose

for technology.†† "Technology is

also a means for us to mount and change exhibits more frequently, which is so

important in the programming side of a museumís charter.† And letís not forget that weíre a

multi-cultural and multi-lingual society; technology can and should be used

to help us convert more of our programs and exhibits to different languages.

"Iíll listen to people who have given their lives to

the museum and, in doing so, Iíll learn about Carnegie Museum of Natural

Historyówhere it is, and where it still needs to go."††

Click on the image

for a larger version.

You are what you eat with†† †††††††††††††††††† ††††††††††

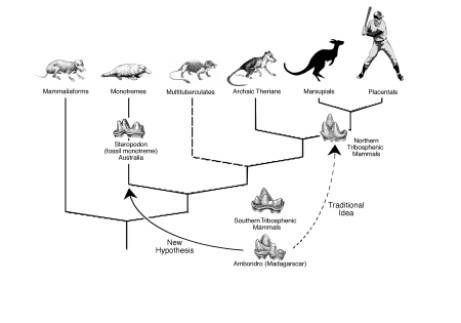

A new idea about the evolution of mammals keeps Carnegie Museum of

Natural History at the frontier of research

You are what you eat with--that's the way biologists who

study mammals see it.† Your mammalian

teeth reveal not only your diet, but also your place on the ancestral tree.

In a recent issue of NATURE

(January 2001), Carnegie Museum of Natural History paleontologist Zhexi

Luo, along with two international colleagues, took a bite out of the standard

theory of evolution of mammalian teeth.†

They proposed that the specialized cutting and grinding teeth of earliest

mammals evolved not once, but twice,†

160 to 110 million years ago, in the Mesozoic Era, when today's

continents were clustered in two† land

masses--Laurasia, in the northern hemisphere, and Gondwana in the south.††

In both places, say Luo and his fellow scientists,

ancestral mammals developed specialized teeth called "tribosphenic

molars" for cutting and grinding food.†

"Tribo" is Greek for cutting, and "sphenic" is

Greek for grinding.† The earliest

mammals that had these teeth, could cut their food and grind it for

digestion, enabling them to develop more omnivorous feeding.† Tribosphenic teeth are a key development

that enabled marsupials (which carry their young in pouches, like opossums)

and placentals (which bear their young internally, within a placenta, like

dogs and cats), to thrive after the extinction of dinosaurs.

The earliest "for cutting only" teeth let

mammals slice up tiny and fragile insects, but did not let them crush tougher

food or chew plants. The tribosphenic molar lets the animal pulverize food

because a cusp on the upper tooth fits like a pestle into the mortar-like

basin of the lower tooth. This action enabled animals to crush seeds and pulp

fruit, and to grind up leaves--in effect, to become more successful and,

therefore, to diversify throughout the world.

For decades paleontologists thought that because

tribosphenic teeth were so unique and structurally intricate, they must have

evolved from a single origin in the Mesozoic time. But now Drs. Luo, Cifelli,

and Kielan-Jaworowska demonstrate that tribosphenic molars evolved twice in

the Mesozoic time, in both the northern and southern clans of animals that

lived on two different land masses.

"To have it evolve once was good, but to have it

evolve twice is even better, because of the currently available

evidence," says Luo. Such discoveries keep Carnegie Museum of Natural

History scientists at the frontier of†

the theory of evolution.

Awards for two Outstanding Mineralogists

The Carnegie Mineralogical Award for the year 2000 was

given to distinguished collector and philanthropist Dr. F. John Barlow at the

Tucson Gem and Mineral Show on February 10, 2001.† Created in 1990 at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the

award focuses on specimen mineralogy and is internationally prestigious.† The list of past winners reads like a

who's who in the world of mineralogy.†

Dr. Barlow is associated with the University of Wisconsin at Oshkosh,

and for 30 years has generously shared his knowledge and outstanding specimen

collection with students and fellow mineralogists.

Marc Wilson, head of the section of Minerals and Gems at

Carnegie Museum of Natural History, also received an award from the AFMS

Scholarship Foundation, Inc., in recognition of his public service.† Representing the Eastern Federation of

Mineralogical and Lapidary Societies, Wilson has the opportunity to select

two outstanding graduate students in mineralogy to receive funding for their

studies for two years, at a rate of†

$2,000 per year.† Wilson said,

"This annual award means a great deal to me because it comes from the

public that I serve."

|