|

|

Claude Monet An Interior after Dinner, 1868-69, oil on

canvas. Washington, D.C., National

Gallery of Art, Mr. and Mrs. P. Mellon

|

Light!

The Industrial Age 1750-1900, Art & Science, Technology & Society

April 7 – July 29, 2001

By

Ellen S. Wilson

Not

long ago, National Public Radio host Scott Simon referred to “the company

that bottled light” in a story on a corporation that manufactures light

bulbs. It’s an interesting thought, that those somewhat bottle-shaped bulbs

can contain such a mystical phenomenon. Light, however, is not so easily

confined. It tends to leak, to spill out of the closet on a dark morning, to

ruin cover-ups, reveal secrets, blind us, or reassure us. It’s a wave, it’s a

particle, it’s actually both. It makes a Turner sunset different from a Van

Gogh sunset, a Degas interior different from a Monet. We can’t live without

it, but we take it for granted until the power goes out. What difference does

it make in our lives, our art, the way we see and think?

Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum of Art,

and Andreas Blühm, head of exhibitions at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam,

began to ponder some of these issues in 1997, and the results can be

experienced in Light! The Industrial Age 1750-1900, Art & Science,

Technology & Society, opening in Pittsburgh April 7. The exhibition

is exclusive to the Amsterdam and Pittsburgh museums, and during its

Amsterdam run London's Daily Telegraph critic Richard Dorment called

it “by far the most important exhibition in Europe.”

“We think of light as unchanging, constant, available, and none of

that is true,” says Lippincott in explaining how the exhibition came into

being. “The most difficult thing to understand is how light was perceived

historically. You can compare it to the changes brought about by the digital

age, and its impact was probably just as profound.” The development of

artificial light and the new lighting methods that quickly became available

changed how people saw, and that changed how they lived.

|

|

The exhibition focuses on innovations in lighting during

the Industrial Age in Europe and America, and how artists responded to them.

There are five broad subject areas, beginning, appropriately, with Rays of

Light, and society’s first attempts to understand and control them. This

section recreates Newton’s prism experiment, which demonstrates that a beam

of light passed through a prism is broken into the separate colors of the

spectrum.

In addition to early magic lanterns, microscopes and

cameras, there are rare editions of the scientific texts offering different

theories about the nature of light. A 1704 edition of Newton’s Opticks,

for example, explains that light is made up of particles that behave

predictably, according to mathematical principles. In the previous decade,

Christiaan Huygens had theorized that light was actually a wave and behaved

something like sound waves. Today, we understand that light can behave as

either a wave or a particle, but Newton’s and Huygens’ contributions to the

scientific dialogue were, according to Lippincott, more important that

identifying the makeup of light. “They got people thinking of light as a

material, manipulatable thing, not a gift from God,” she explains. “This was

a completely new concept, and it opened up light as a subject for

investigation, and for art.”

Jean Siméon Chardin takes up the subject in his still life Glass

of Water and Coffeepot, ca. 1760. Despite the simple title, the painting

captures the property of refraction, or the way light bends when it passes through

transparent materials. An understanding of refraction is essential to making

lenses for telescopes and microscopes, and here Chardin demonstrates his own

scientific knowledge. Other elements in the painting – a dark brown

coffeepot, and bright white garlic bulbs – illustrate the behavior of light

as it bounces off some surfaces and is absorbed by others. Chardin may not

have worked out any mathematical formulas in order to paint so accurately,

but he was surely familiar with the current thinking on the behavior of

light.

In the 1780s, when the Argand lamp made artificial light brighter, a

new appreciation for natural light arose, with a sense of the moral authority

linked to a phenomenon beyond human control. Lippincott and Blühm have

assembled in part two of the exhibition, The Light of Nature, a

selection of landscapes in which the real subject is sunlight. What

immediately strikes the viewer is how different light appears in the various

paintings, all of them completed within at least a few decades of each other.

“During the 19th century, physiologists studied the way

the eye and the brain perceived light, and how light influenced emotion,”

Lippincott explains. “They had long known that music, or sound waves,

affected emotion and now painters began attempting to manipulate the viewers’

emotions through the use of light waves, or color.”

|

|

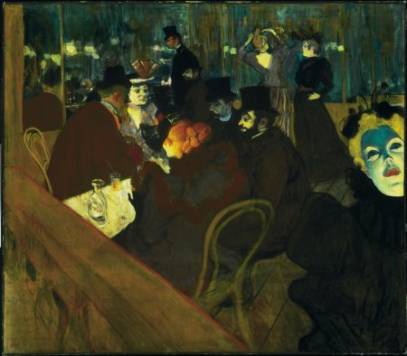

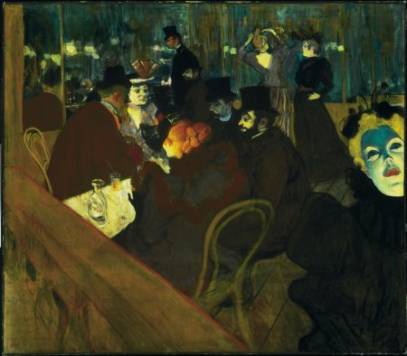

Henry Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec At the Moulin

Rouge, 1892-95, oil on canvas. Art

Institute of Chicago

|

Ford Madox Brown’s The Pretty Baa Lambs, 1852, is,

according to the curators, probably the first 19th-century picture

painted for exhibition almost entirely outdoors. Ford said he intended to

represent the effect of sunlight on the scene, and that hanging the painting

in the false light of the gallery led viewers to misinterpret it, to see it,

in effect, the wrong way.

Just 20 years later, when Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro

produced his own study of outdoor light in The Crossroads, Pontoise,

1872, the results were entirely different. Both paintings show bright, sunny

days, but Brown painted the individual blades of grass, and Pissarro’s grass

is made up of broad swatches of various shades of green. Both look equally

grassy, but according to the exhibition catalogue, Pissarro believed that “bright

sunlight flattened detail and diminished color.” Thus his sky is a pale blue,

especially near the horizon, and a white house in the background is merely

sketched in. Brown’s sky is achingly blue, and every fold of drapery is crisp

and distinct. It is difficult to reconcile the two paintings with the

artists’ shared intention: to capture the realistic effect of bright, natural

light on an outdoor scene.

|

|

“Did light behave differently in Britain’s notoriously

humid atmosphere, as compared to France’s drier one?” the curators ask in the

catalogue. “Or did each artist go out into the sunshine expecting to see

things differently from certain artists of the past – and consequently each

found a different version of the truth?” One thing is clear: natural light is

seen in a positive way, healthful, beneficial, and aligned with all the

purity of lambs, motherhood, and visual truth.

In the section Makers of Light, one of the first things

visitors will see is Thomas Edison’s flickering film of the Buffalo

Pan-American Exposition of 1901, the first motion picture shot at night by

artificial light. Marvelous to look at today, understanding its historical

impact requires a powerful imaginative leap. As Dorment points out, “Nothing

– not television, not space travel, not computers – gives us any idea of the

awe our great-grandparents must have felt when they saw the world illuminated

by electricity for the first time.”

Until that first dim candle, light had been entirely in the hands of

God. With the advent of the telescope, it became evident that not only was

light a scientific phenomenon, life on earth might be as well. This change in

thinking is illustrated in the different plates made by Gustave Doré for an

edition of the Bible in 1865 and 1866. In the French edition of 1865,

accompanying the text, “And God said, ‘Let there be light,’” God is portrayed

as a magnificent figure raising his arm in a burst of sunlight. In the

English edition of 1866, for a Protestant readership, he is replaced by a

cloud.

Was it hubris to think that God was not responsible for so profound

a gift as light? Was it unnatural and therefore evil to light up our rooms

and factories and go on working, long after the sun had set?

John Martin’s 1841 painting Pandemonium, a vision of the

palace of Satan lit by what appear to be gaslights, suggests that it was. The

gaslights seem to be related to the flames of hell erupting at the feet of

the devil, and the scene itself, some critics say, resembles London’s Pall

Mall, the first street in London to be lit by gas, and a favorite playground

of libertines.

|

|

The last two sections of the exhibition, Personal

Lights and Public Lighting, explore these questions further

because, as Lippincott explains, the moral issue about the human right to

create light flips back and forth. If light enables new sorts of bad

behavior, it also exposes it, as the 19th-century police lantern

with bulls-eye lens demonstrates. Wilhelm Bendz’ The Life Class in the

Academy of Fine Arts, 1826, shows people waiting to begin work while the

lamps are lit, the point being that good work requires good lighting.

Lamp and hearth light, traditionally symbols of female virtue, can

be the peaceful centerpiece of the family, as in Claude Monet’s 1868-69 An

Interior after Dinner. Or it can be a harsh focal point, as in Edgar

Degas’ Interior, also 1868-69, revealing what the exhibition catalogue

calls “two of the unhappiest people ever depicted in art” in a tension-filled

scene of female misery.

In Public Lighting, visitors themselves may observe the

different kinds of lighting that became available during the Industrial Age.

Van Gogh’s famous painting of 1888, Gauguin’s Chair, contains the

first pictorial evidence that Van Gogh had his house connected to the gas network

in Arles, France. The painting shows a gas jet in the background, radiating

light, and on the seat of the chair a candle, whose flame is made

insignificant by the brighter gas light. In the exhibition, the painting may

be viewed by natural light, open gas flame, incandescent gas flame, and

electric arc light, the four kinds of light vying for dominance during Van

Gogh’s career. Each light shows a markedly different painting.

As light became easier to use, the science behind it became more

removed from our daily experience. When we stopped having to trim wicks and

fill oil reservoirs, we may have lost sight of light itself. “I would like

visitors to the exhibition to understand, when they leave, the extent to

which the quality of light affects them,” Lippincott says.

We may think we understand how light works, but the art and the

technology included in this exhibition show us a more profound truth. It may

be that only an artist can really capture how light makes us see, feel, and

live.

The last two sections of the exhibition, Personal Lights and Public

Lighting, explore these questions further because, as Lippincott

explains, the moral issue about the human right to create light flips back

and forth. If light enables new sorts of bad behavior, it also exposes it, as

the 19th-century police lantern with bulls-eye lens demonstrates.

Wilhelm Bendz’ The Life Class in the Academy of Fine Arts, 1826, shows

people waiting to begin work while the lamps are lit, the point being that

good work requires good lighting.

Lamp and hearth light, traditionally symbols of female virtue, can

be the peaceful centerpiece of the family, as in Claude Monet’s 1868-69 An

Interior after Dinner. Or it can be a harsh focal point, as in Edgar

Degas’ Interior, also 1868-69, revealing what the exhibition catalogue

calls “two of the unhappiest people ever depicted in art” in a tension-filled

scene of female misery.

In Public Lighting, visitors themselves may observe the

different kinds of lighting that became available during the Industrial Age.

Van Gogh’s famous painting of 1888, Gauguin’s Chair, contains the

first pictorial evidence that Van Gogh had his house connected to the gas

network in Arles, France. The painting shows a gas jet in the background,

radiating light, and on the seat of the chair a candle, whose flame is made

insignificant by the brighter gas light. In the exhibition, the painting may

be viewed by natural light, open gas flame, incandescent gas flame, and

electric arc light, the four kinds of light vying for dominance during Van

Gogh’s career. Each light shows a markedly different painting.

As light became easier to use, the science behind it became more

removed from our daily experience. When we stopped having to trim wicks and

fill oil reservoirs, we may have lost sight of light itself. “I would like

visitors to the exhibition to understand, when they leave, the extent to

which the quality of light affects them,” Lippincott says.

|

|

Lapierre, Magic Lantern, ca. 1880 Haags Documentatie.

Centrum Nieuwe Media, the

Hague

|

We may think we understand how light works, but the art

and the technology included in this exhibition show us a more profound truth.

It may be that only an artist can really capture how light makes us see, feel,

and live.

The last two sections of the exhibition, Personal

Lights and Public Lighting, explore these questions further

because, as Lippincott explains, the moral issue about the human right to

create light flips back and forth. If light enables new sorts of bad

behavior, it also exposes it, as the 19th-century police lantern

with bulls-eye lens demonstrates. Wilhelm Bendz’ The Life Class in the

Academy of Fine Arts, 1826, shows people waiting to begin work while the

lamps are lit, the point being that good work requires good lighting.

Lamp and hearth light, traditionally symbols of female virtue, can

be the peaceful centerpiece of the family, as in Claude Monet’s 1868-69 An

Interior after Dinner. Or it can be a harsh focal point, as in Edgar

Degas’ Interior, also 1868-69, revealing what the exhibition catalogue

calls “two of the unhappiest people ever depicted in art” in a tension-filled

scene of female misery.

In Public Lighting, visitors themselves may observe the

different kinds of lighting that became available during the Industrial Age.

Van Gogh’s famous painting of 1888, Gauguin’s Chair, contains the

first pictorial evidence that Van Gogh had his house connected to the gas

network in Arles, France. The painting shows a gas jet in the background, radiating

light, and on the seat of the chair a candle, whose flame is made

insignificant by the brighter gas light. In the exhibition, the painting may

be viewed by natural light, open gas flame, incandescent gas flame, and

electric arc light, the four kinds of light vying for dominance during Van

Gogh’s career. Each light shows a markedly different painting.

As light became easier to use, the science behind it

became more removed from our daily experience. When we stopped having to trim

wicks and fill oil reservoirs, we may have lost sight of light itself. “I

would like visitors to the exhibition to understand, when they leave, the

extent to which the quality of light affects them,” Lippincott says.

We may think we understand how light works, but the art and the

technology included in this exhibition show us a more profound truth. It may

be that only an artist can really capture how light makes us see, feel, and

live.

|