|

|

|||

|

Back Issues |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

Adrian Piper: A Conversation

Thomas

Sokolowski, Director of The Andy Warhol Museum, talks to multi-media artist

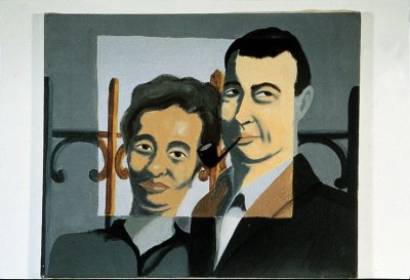

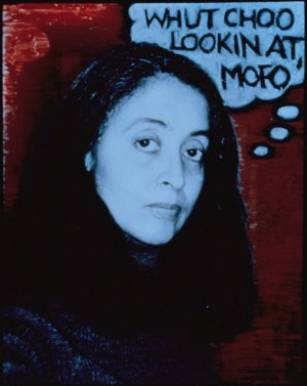

Adrian Piper Pittsburgh gets a rare opportunity to experience works by contemporary artist Adrian Piper in a three-part exhibition from March 4, 2001 through May 13, 2001. The public will see two exhibitions: Adrian Piper: A Retrospective, 1965-2000 curated by Maurice Berger; and MEDI(t)Ations: Adrian Piper’s Videos, Installations, Performances, and Soundworks 1968-1992 curated by Dara Meyers-Kingsley. Piper will also create a site-specific work for The Andy Warhol Museum called Prayer Wheel I. Adrian Margaret Smith Piper's objects, installations, performances, videos, and soundworks are distinguished by their direct, active relations between artist and spectator. She has focused on racism, racial stereotyping and xenophobia for three decades, and presenting her artwork at venues such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Hirshhorn Museum, and the Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. She received her Ph.D. in Philosophy from Harvard University, and teaches Philosophy at Wellesley College. Museum director Thomas Sokolowski has previously exhibited

Piper's work in New York City, and she has visited The Warhol before, at the

invitation of the director and associate curator Margery King. Thomas Sokolowski: You're a peculiarity in many ways. Adrian Piper: Thanks, Tom! No, I mean it. First of all because you are an artist, and artists are peculiarities. And, as you remember when we did that project together in New York, the notion that you are engaged in two equally powerful and serious fields, working as a philosopher and as a visual artist. You have been able to keep those distinct worlds quite distinct. Why did you choose that path? Well, to a certain extent it had to do with my desire not to force any connections artificially, between the two fields. I have a set of fairly well defined interests in art, and a set of well defined interests in philosophy, and there are all sorts of ways in which the two might interconnect. But they do not necessarily interconnect, for me personally. The way they do interconnect for me personally is something that I always find out in retrospect. And it's better that way. Because if I try to find the connections consciously, and then try to develop the connections consciously, it feels as if everything is going on in too much of an intellectual level. It really has to come from a deeper place than just the intellect. And so I basically have just let things take their own course. So that is part of the answer. But the other part has to do with the nature of the two fields in question. There really is not very much overlap between academic philosophy and the art world. There is some overlap, with some individuals who do aesthetics. But for the most part they are pretty distinct fields. When I am in an art context, for me to start spouting philosophy is going to guarantee that I will put everyone to sleep. On that, some people might say

that they don't feel comfortable in the world of contemporary art, that the

same is true for visual art. Do you think that is true? For your art, your

work and the way you have related to visual arts audiences? I do think that is true as well for visual art. If a person is not knowledgeable about the world of contemporary art, or seeing and talking and hearing about contemporary art, and has to juggle with the concepts and the approaches to contemporary art that anyone in the art world is totally familiar with, that can be a frightening, threatening and disorienting experience. It definitely works both ways. There is no doubt about it. The technical and evolved nature of each field, relative to the other, effectively keeps them apart, naturally. The normal guy who does not have an interest in following either field is a stranger in both lands, because both are specialized disciplines. To simply walk into a contemporary art gallery and expect to understand what is on the walls, and why, is to some extent very naïve. And that has not been true since probably the 17th century. That really brings us to your work, to someone like yourself, who really is one of the pioneers, a rich practitioner from the beginning of the Minimalist and Conceptual art movements. Where you sort of jump ship with your formalist friends is your choice of subject matter, i.e. race and xenophobia, and human interaction and identity politics. One might say if you are talking about racial prejudice, doesn't that perforce throw you into a kind of populist view? Racism is a thing that stands or yells or smells in your face, and shouldn't those affective elements be obvious if your work is about that. When you walk into a contemporary gallery and you see a work about prejudice, shouldn't that be obvious? And if it is not obvious, how can it affect the change that ostensibly an artist is trying to make in that arena? Yes. I think you're right, and I think that is the way in

which my work operates on many different levels. The reason my work tends to

draw audiences that often do not find themselves in a museum context is that

there is an aspect of it that can speak to anyone. I like to think that is

the truly universal aspect of it, because those issues and the approaches I

take to the issues are in fact very widely accessible, and I think And then there are deeper levels only accessible to people who know the history of minimalism and conceptualism, and have an interest in formal issues of structure and balance and proportion, and that kind of thing. And then there is a deeper level that has to do with the relation of the work to philosophical and spiritual issues. There is something in the work that can draw a person if they are just minimally receptive, regardless of where they're coming from. That's what I like to hope.

Very often, the hidden assumption when you hear that all-art-is-for-everyone message, is that all art is going to be soothing. And when that doesn't happen, those expectations are violated. And having one's expectations violated can be a very distressing experience. I think very often in the kind of work I do, the problem is very often, not that the work is accessible, but that it is too direct. It's almost the opposite problem. People do not wanted to be confronted with a clear and unambiguous position on something. They don't want things to come in too quickly, without any kind of mediation. That can be very upsetting. That 's not what they are expecting. For most people, museums are the world of culture and the world of academia, the sublime venues for mediation. But the notion of the street, or the real world, is the place for non-mediated direction. So in a sense what you and many artists are saying is that "This is the street." I think this goes against that particularly American notion that museums are zones of tranquillity. That's where the shock comes. Do you find, in a weird kind of way, that because there is that kind of shock, one can be more effective in the galleries than on the street? You know, I'm worried about drawing any too specific comparisons. I have had some experience doing direct political organizing--as opposed to the ways that I try to communicate with people through my artwork. I think it is a real toss-up as to which is more effective. The benefits of sustained political organizing are pretty obvious. I think maybe we are just starting to explore the ways in which art can be socially effective as well. In the case of art, the potential is there for really internal psychological and emotional change. Because you are dealing with viewers one-on-one, in a very personal and direct way, rather than as part of a group. When someone is standing in front of a work of art, they are in direct relation to that work of art. They are experiencing the work of art without any intermediary between them. I think, again, it depends a great deal upon what the viewer brings to the work of art, what set of assumptions, how open the person is, how mentally and psychologically flexible they are. There are all sorts of factors there. But the fact that a work of art can address a viewer directly and in a one-on-one relationship, is a very important catalytic function of art, that can't be replicated by political organizing or other kinds of political activities. Well, I would like to think that only art is uniquely placed to do just that--to catalyze those very deep changes in a person that come from seeing something, and registering it on many levels, not all of which are accessible to consciousness. So the first time around the person thinks, "Oh, that's very pretty." The second time around they think, "Oh, hmmm, why are all the people Black?" And then the third time around, they think, "So here I am a white person looking at a picture of all Black people…what does that mean?" It just goes deeper and deeper, and there are more and more questions that can be asked. If the person is subject to questioning and self-analysis. I think one of the most potent works that you have made, and one of the more potent works on identity politics and introspection, is your "Cornered" piece." The viewer comes around the corner and there you are…this calm , mild-mannered "librarianish" woman wearing pearls (the artist herself seen on a t.v. screen), sitting there, and you say, "This person has something to say to me, she's someone I can trust..." And you speak in this moderated tone, and all of a sudden what you don't expect starts pouring over you. You're stuck. You're sort of like Sister Wendy in a sense (but not unattractively). This goes back to the street discussion we were having--aggressive and in-your-face. I remember you said to me one time, "I grew up as a middle-class person, and even if someone is a disgusting pig at a party, my notion is not to slap him and throw a drink in his face. That kind of upfrontness is just unpleasant." Whereas if you come in and you inveigle someone, then you say, "Oh, this is not what I thought." There is a comfort level, that that piece has. And then you are seduced, trapped. But a piece like "Cornered" has a wonderful narrative that just holds you there. That is a rare occasion. Over and above that the fact that that piece speaks so articulately about race, it just holds you. "What is she going to say next? What thing is she going to reveal now?" I have to say, I am of course flattered. But I am also delighted to hear you say that. I remember when I was producing that piece. The script went through so many different changes, and so many experiments with ways of presenting this material. There was an early point at which I was very worried about whether a long shot like this, with no edits whatsoever--twenty minutes with no edits--could hold people's attention. There was one version that had lots of editing, cutaway shots, lots of jokes. It was much messier than the final version. I felt that I needed to do that, to keep people's attention. In the end, I decided, "Well, to hell with this. I'm a minimalist. It's about clarity and simplicity. That's just the way it's going to have to be. " Don’t you think that we're really all artists, always telling the same story, in subtle ways and different ways, and sometimes you hit a plateau…but it's always the same story. I think that's true. You tell the story, and each time you tell it you go more deeply into it. And you draw out more implications, and add more detail, and it acquires richness and resonance and depth because each time you transcend the familiar and you take it one level deeper and you move towards the unfamiliar. On a different note…when you came here a year and a half ago, Margery King, John Smith and I talked about the Warhol Archives,and how the archives work in terms of your personal life and in terms of your family. Do you remember? Do I ever remember! Absolutely. It was because of my visit to The Andy Warhol Museum and what I saw in the archives, and how the matter of personal work, as well as artistic work, had been handled there, that I decided not to destroy my own artwork. The documentation of my work was actually a project that I had been working on for some time--getting all my work documented, getting slides of everything, and getting everything inventoried. So that I could then absolutely destroy most of the work that I have been carrying around with me. Why would you do that? Aside from asking who wants to store all this, and and how much does it cost to store? Those things are burden enough. I don't want to underestimate them. I was feeling oppressed by having to carry around all of this stuff. But it is also a matter of the kind of artist that I now recognize myself to be. I am someone who does pretty well in terms of getting attention from the press, and discussions by critics about my work. I take pride in knowing that my work generates discussion among thinking people, and that they want to write about it, and kind of puzzle through it, and come to conclusions about it. That seems to be the way my work functions, as opposed to being the kind of work which is a hot-market property. If you just wait around two or three hundred years, I think my work will be a hot-market property, precisely because of its place in art history, and the amount of writing it is generating. It's pretty secure. But at the moment, I don't sell a lot of work. And that's the price I pay for doing the kind of work I do, and I'm at peace with that. And I have a day job which I don't intend to quit, so there is no problem there. But given that, it just seemed to me to be really pointless to have to deal with the physical realities and demands, of the work itself. The Warhol visit really changed my life, Tom. You have no idea. Here's what I did. I had been living in Wellesley faculty housing in a three-bedroom apartment. I moved down to my mom's cottage on Cape Cod, and I built a very large addition onto that cottage. I contracted all of the work myself, for an art storage basement, a library and a studio. I now have an archive of my own. It's very small--not even close to the scale of the Warhol Museum. But I have a respectable place to store all of my artwork and archive all of my papers. I basically have my artistic affairs in order. If I hadn't spent that time at the museum, I would basically have taken it to the dump. O my God. If the Andy Warhol Museum does nothing else, except have a major American artist say that, I can now go to heaven! |

|||

|

Back Issues |

|||

|

Copyright (c) 2001 CARNEGIE magazine |

|||