Light!

The Industrial Age 1750-1900: Art & Science, Technology & Society

By Ellen S. Wilson

Through July 29

The world notices when two museums collaborate on a blockbuster

exhibition such as Light! The Industrial Age 1750-1900: Art &

Science, Technology & Society.

Andreas Blühm, head of exhibitions at the Van Gogh Museum in

Amsterdam and co-curator of Light! with

Louise Lippincott of Carnegie Museum of Art, reported that 268,000 people

visited the exhibition in Amsterdam.

“There were more local visitors, more Dutch visitors, and visitors

with more wide-ranging interests,” Blühm said. “It was a different crowd, and that is what we wanted. Everyone had a different favorite

object.”

During the Amsterdam run, the international press

praised the exhibition, and now that it has opened in Pittsburgh (the only

other venue in the world), it has been featured on CBS News' Sunday Morning, in the New York Times, the Washington

Post, in on-line magazines, and many other media outlets, both local

and national. A lengthy and

enthusiastic review by Todd Spangler for the Associated Press should run in

newspapers all over the country, a boon for the city as well as the museum.

Beginning, as Spangler points out, with “homage to Isaac

Newton” and a rainbow on the walls of the dimly lit gallery, the exhibition

spreads out to include early scientific instruments, domestic

paraphernalia, and a look at how artists used light, or tried to capture

its effects. The exhibition ties in

with the city-wide campaign Pittsburgh

Shines, a project of the Greater Pittsburgh Convention and Visitors

Bureau Office of Cultural Tourism to highlight city attractions and

cultural events. Here, as in Amsterdam,

the museum is expecting not only numerous visitors, but a crowd as diverse

as the exhibition itself.

|

|

|

Eastman Johnson,

Jewish Boy, 1852

|

Round-Up of Summer Exhibitions

Linda Batis, associate curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum

of Art, describes Portrait/Self

Portrait as “a look at fame and how it fades.” The exhibition features works by Dürer,

Rembrandt, Degas, Picasso, Mary Cassatt, Winslow Homer, and many other

major artists from the Renaissance to the mid-twentieth century in a survey

of how the personal and emotional life of the subject can be captured on

paper. While many of the portraits

originally depicted the wealthy and powerful, in many cases the celebrity

did not last, and the works are enjoyed today more for what they reveal

about the artist than for what they convey about the subject. The exhibition runs through October 14.

In the Heinz Architectural Center, Landscapes of Retrospection:

The Magoon Collection of British Drawings and Prints, 1739 – 1860

and Still Rooms &

Excavations: Photographs by Richard

Barnes are both on view through September 2. The Magoon collection from Vassar College catalogues

Britain’s built and natural heritage, an appreciation of which rose during

the Industrial Revolution. Richard

Barnes’ evocative photographs document the 1990s’ expansion of the

California Palace of the Legion of Honor, and the excavation of the gold

rush-era burials field discovered beneath it.

David Carrier is the juror of the 91st annual

Associated Artists of Pittsburgh exhibition at the Museum of Art from

August 24 - September 24. Carrier,

Professor of Philosophy at Carnegie Mellon University, is widely known for

his work in art criticism and his study of the history of art history.

And in the Forum Gallery, the National Society for Arts

and Letters exhibition of sculpture will be on view through September

2. This society was formed in 1944

to sponsor competitions and encourage careers in the arts. National jurors for this year’s competition

included Thomas Sokolowski, director of The Andy Warhol Museum, and

sculptor Thad Mosley.

|

|

|

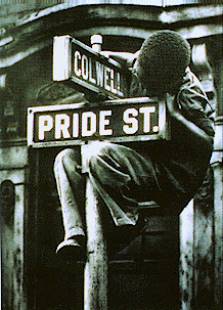

Eugene Smith,

Pride Street, 1955

|

Dream Street: Photographs by W. Eugene

Smith

November 3 – February 10, 2002

From an early age, photographer Eugene Smith had a

vocation: to shoot “life as it is.

A true picture, unposed and real.

There is enough sham and deceit in the world without faking life and

the world about us. If I am

shooting a beggar, I want the distress in his eyes, if a steel factory I

want the symbol of strength and power that is there.” These thoughts are recorded in a letter

he wrote to his mother at the age of 18.

Smith was driven to carry out his plans; he let nothing stand in the

way of getting the shot he wanted, of documenting “life as it is.”

That same year, Smith dropped out of Notre Dame

University and moved to New York to begin photography school. He quickly lined up a job at Newsweek as well as free lance

assignments. Always single-minded

and passionate about his work, and insisting on shooting his pictures his

way, Smith lost his job at Newsweek,

and gained a well-deserved reputation for being impossible to work

with. This tenacity and insistence

on his art served him well, however.

His photographs from World War II, most of which were published in Life, are some of the most dramatic

of the period.

Injured by an exploding mortar shell (he had a habit of

risking personal safety for a good picture), he worked for Life after his recovery, spending

months on minor assignments and bickering endlessly with the magazine’s

editors over the layout of his work.

The rigid structure of a weekly magazine could not contain him, and

his youthful comments about a steel factory proved prophetic. Smith’s first freelance assignment after

leaving Life was a documentation

of gritty, dramatic Pittsburgh in the mid-1950s, and the city, with few

pretensions, proved the perfect subject.

This is the first museum exhibition of 200 of the photographs from

Smith’s Pittsburgh project.

|