|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

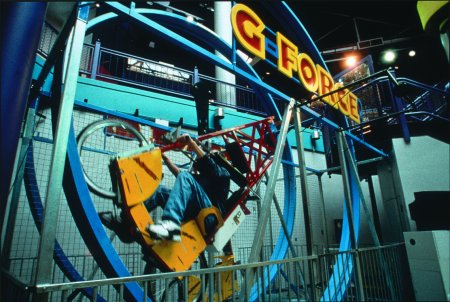

Scream Machines: the Science of Roller CoastersSeptember 30, 2000 -- January 7, 2001The thrill of the ride results from a perfect package of fear and illusionA heavy, padded bar falls across your lap, locking you into the tiny seat. There is no escape. You're propelled forward--transfixed by the seemingly endless track rising before you. Your stomach clenches. Clacking noises reverberate around you. The ascent goes on, and on--teasing you, testing you. And then, almost without warning, you're plummeting to Earth at such a dizzying speed you feel airborne. Your body is whipped to the left and then to the right. You're upside down. You're upright. Are you coming or going? A scream rips from the depths of your soul. You are on a roller coaster and having the time of your life. An estimated 290 million people flock to amusement parks annually to experience this sensation. Last year, Pittsburgh's Kennywood Park hosted ore than a million people with 1,800 of them riding the Steel Phantom, the park's largest coaster, every hour. "People like to experience fear...as in horror movies and haunted houses,” says Bill Linkenheimer, a Pittsburgh resident and president of the American Coaster Enthusiasts. "Just as in those things, you know you aren't REALLY putting yourself in danger, but it's a way of going out of control at crazy speeds without risking your life." Adds Mary Lou Rosemeyer, Kennywood Park's publicity director, "[Roller coasters] get the adrenaline going and there's a challenge in it--overcoming your fear." Explore this love/fear relationship at Carnegie Science Center's new exhibit, Scream Machines: The Science of Roller Coasters. This 6,000-square-foot exhibit, with 11 multi-station interactive components, has all the heart-pounding, stomach-churning, and head-spinning experience of any roller coaster ride. What exactly does happen to you, scientifically speaking, on a roller coaster? For one thing, you are subject to new effects of the laws of gravity. Right now you are experiencing a 1-G force--the normal gravitational pull that holds you to that couch. But if you go fast enough, in a car or a roller coaster, you're pushed with a force equal to the weight you normally feel due to Earth's gravity. Ever felt as if you were being thrown sideways in a car that was turning too fast? Then you've experienced greater than 1 G-force. Once your body begins moving it will continues in a straight line until something forces it to change--such as a roller coaster curve or loop. Your body resists the change, so you feel thrown outward. That's centrifugal force, G-force or, as astronauts say, "pulling Gs." The Revolution roller coaster at Six Flags, Magic Mountain in Valencia, California, gives you a whopping 4.9 Gs--1.5 more than a shuttle launch--double that and jet pilots begin to black out. Confused by all these Gs? Climb on Scream Machines’ “G-Force!,” a bicycle ride that circles an 18-foot loop, and feel high and low G forces as well as free-fall--that weightless sensation (negative Gs) of going over a thrill ride hill--when the G force upward cancels gravity's normal one G downward. Roller coasters create thrills primarily

through a sense of illusion and the psychology of fear. Think about it.

The average duration of a coaster ride is only two and a half minutes,

and the roller coaster begins losing momentum once it hits the bottom of

a hill. So you're never going faster than you go after the roller coaster's

biggest drop. But while shooting through the ride it seems like you've

been going faster than the speed of light forever. That's illusion. As

you nervously prepare for take-off in any typical-sized roller coaster,

such as Kennywood Park's Steel Phantom, the track is about 3,000

to 4,000 feet long--but add loops and

A good roller coaster designer creates this fear and speed illusion by making the ride's turns tighter. The Steel Phantom, which ranks in the top five of all roller coasters for speed, only reaches 80 miles per hour--and you know you've topped that on the Turnpike. But add loops, corkscrews, tight turns, incredibly steep hills, whipping wind, the open car, and the scenery whizzing by, and comparing it to a highway drive is like comparing riding an elevator to skydiving. The perceptual phenomenon created as objects race and twirl by coaster riders is demonstrated at Scream Machines’ “Tumble-Vision” display. Tumble-Vision features a stationary bridge and rotating walls--you aren't moving, but you feel as if you are. A similar apparatus is used by NASA to train astronauts. Albert Einstein noted in his book The Evolution of Physics that roller coasters are a perfect example of energy conservation in a mechanical system. From the potential energy that exists on the top of the first hill to the conversion of kinetic energy as it plunges down the drop, the roller coaster uses only gravity and momentum to perform. In fact roller coasters are such a good place to learn about physics that for the past 13 years Kennywood Park has hosted an annual physics test. Thousands of students from Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, and West Virginia climb aboard roller coasters to learn about G forces and hop on the 251-foot tall Pittfall, which plunges to Earth at 100-feet per second, to experience free-fall first-hand. "Every ride works as a lab," says Rosemeyer. "[The test] is very serious work, but the kids have a ball. It's a great way to apply the classroom to the real world." The same goes for Scream Machines, but

without the exam it's all a ball. There's the Revolver display where visitors

bowl in a rotating room to see how the physics of a simple motion can react

in weird ways--the weird ways that push and pull your body when it hits

a coaster curve and your body wants to go straight while the seat it's

strapped to goes in another direction. Or check out the Black Plague. Built

by Mike Graham, it's one of the most detailed working models of a roller

coaster anywhere. Inspired? Build your own coaster at Computer Coaster

and see if you'd engineer the best thrill-ride ever--or create a ride of

chaos and

Speaking of doom, there's no need to fear a thrill ride. Roller coasters are exceptionally safe--just ask Linkenheimer, who's climbed aboard more than 400 coasters (he can't name a favorite). The mortality rate for coasters is one in 90 million--and of the 34 people who have died in roller coaster-related accident in the last 26 years, the majority were not exactly practicing the safety rules. Yep, there's a reason you're not supposed to stand up on the Steel Phantom. Even so, some people would rather be eaten alive by chipmunks than strap themselves into a whirling dervish. But if you've wondered if an Evel Knievel lurks beneath your Casper Milquetoast exterior, take Scream Machines’ “Thrill-Seeker Test” and find out if you are a closet Type-T--a thrill seeker. For those out there who need a good dose of Pepto Bismol just seeing a roller coaster, Scream Machines has exhibits explaining how the brain and fluids in the inner ear can turn a stomach of steel into a heaving mass. End the day with a coaster ride. Okay, not a real ride--Carnegie Science Center isn't that big--but viewing five of the world's greatest coasters on an enormous video screen is so close, you'll feel the wind in your hair. And remember: keep your arms and legs in the car at all times.

Want more? Check out these Web sites: www.rollercoaster.com

Features a list of the top 10 coasters and theme parks, with Ohio's Cedar

Point ranking as the number one park (Kennywood

www.thrillride.com

Features links to sites such as Six Flags, Florida Theme Parks, Theme Parks

of New England, Kennywood, Cedar Point, and the

www.rcdb.com Features a database of more than 600 roller coasters in North America. It also has pictures, coaster statistics (height, length, drop, speed, and duration), and coaster demographics (age, builder, and type--wood or steel). www.coasterquest.com Answers questions from how a coaster is built to how lap bars stay locked.

Roller Coaster TimelineWhile roller coasters usually conjure up images of summer fun and high-tech wizardry, they have a surprisingly long--and cold--past. Here'sa timeline:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All rights reserved. E-mail: carnegiemag@carnegiemuseums.org |

|||