|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Gem and Mineral ShowWant to put a sparkle in your eye? The third annual Gem and Mineral show will do it. The gala preview party is on Thursday, August 24, and the show opens on August 25. On Saturday, August 26, early birds will be treated to great food and fun with a mineral auction, featuring pieces from Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Houston Museum of Natural Science, and the Harvard Mineralogical Museum among others. The three-day Gem and Mineral Show runs from August 25 – 27 in Sculpture Hall, Architecture Hall, the Music Hall Foyer, and connecting hallways. Entrance to the Show is $2.00, plus museum admission. The preview party fee is $125. Marc Wilson, head of the museum's section of minerals, expects this to be the best show yet, featuring rare and exciting objects that Pittsburghers don't usually get to see. The show will feature classic European specimens and spectacular exhibition pieces. Visitors will be able to do more than just look---jewelry, gems, minerals, and lapidary art will be available for purchase in all price ranges. Gem Artists of North America will be returning, along with some of the Pittsburgh region’s finest jewelers. Moses Jewelers of Butler, Joden World Resources of Grove City, Orr's Jewelers of Pittsburgh, and Antiquorium Auctioneers of Geneva, Hong Kong, and New York will all have some of their most dazzling pieces on display and for sale. A special feature on display this year is a selection from the museum’s own priceless H.J. Heinz watch collection, 31 antique timepieces dating back to the 17th century. The exhibit features some of the world's finest examples of European watchmaking from England, France, Germany and Switzerland. Expect to be dazzled by a 1622 German pocket sundial made of gold and ivory, as well as a gold pocket watch with enameled scenes that belonged to Admiral Horatio Nelson, made in 1790, by the renowned watchmaker Peter MacDonald. Bring the kids along for heaps of fun things and take-home activities for children to do in the ground-level classrooms. The kids will be able to put together their own collection of 12 rocks and minerals. There will also be lapidary art and demonstrations, as well as a small geode hunt. Each child will be able to take home a specimen from the “dig box,” filled with treasures just waiting to be discovered. For more information and to make reservations for the Preview Party

and the Gem and Mineral Auction, call 622-3232.

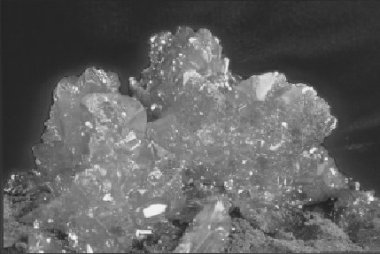

Spectacular Orpiment Crystals Donated to Museum 186w/1204ch Newmont Mining Co. of Denver, Colorado, has donated a spectacular specimen of orpiment crystals to Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The company discovered the rare specimen at its huge Twin Creeks open pit mine in Nevada. Composed of arsenic and sulfide, Twin Creeks crystals have been called some of the most magnificent orpiment specimens ever found in North America. The word “orpiment” for the orange-yellow crystal comes from the Latin aurum for gold, and pigmentum for color. During the process of low-grade large-tonnage mining operations, Twin Creeks miners uncovered this specimen in an area containing a large deposit of orpiment crystals. The important find caused mining operations to be interrupted while an outside company was brought in to retrieve the crystals. After harvesting, the crystals were prepared, treated and trimmed, and then Newmont Mining Co. donated the best specimens to museums across the country. While appearing small next to some of the museum's larger masterpiece specimens, the crystal's great value lies in its rarity. The museum expects to hold a gala unveiling for the orpiment crystals

later this year.

Insects: More Space for a National ResourceOne look at the almost century-old entomological storage area and cases, tucked back in the area called the Holland Room, and you understand Associate Curator of Invertebrate Zoology John Rawlins' preoccupation with space.Named after the museum's early director and first curator of insects, William Jacob Holland, the area is dimly lit, with barely enough room for two people to pass. Archaic storage cases stacked from floor to ceiling are filled with specimens of bugs. The area is only one of several on the museum's third floor, housing what has been called a national treasure. This is one of the country's top-ten insect collections. The National Science Foundation (NSF) responded to Rawlins' most recent grant request for better storage facilities by awarding $378,661 for two years, specifically for the department's Lepidoptera, or butterfly and moth, collection. The award makes available 4,372 storage drawers for 1,002,000 specimens. The new drawers will fill the last remaining spaces of department's compactorized storage systems - or compactors. In 1980, the department first received NSF grant money for expansion of its storage capabilities. It was the start of what Rawlins calls "the 20 year war" to improve storage. Then in 1995, the museum received the largest per diem award for zoology that the NSF had ever made up to that time -- $900,000 over three years for expansion of the Lepidoptera storage facilities. What makes the year 2000 award so special is that the proposal was funded in full, and came with no strings attached, meaning no institutional matching funds were required. The insect collection had largely been bypassed for years when Rawlins first visited the museum in 1979. He was shocked to find a high level of disarray within the storage facilities and collection. "When the staff began to unearth everything in 1980, it was very scary; it was just too big. They found stuff everywhere that wasn't labeled or processed, or that was handled callously." Rawlins found cases covered with a thick coating of black soot, accumulated over decades of lying around. Incredibly, after cleaning, he found the contents to be in perfect condition. When a specimen collected in 1880 is compared against one collected in 1980, scientists are hard pressed to tell the difference. According to Rawlins, the amazing thing about insect specimens is that nobody knows exactly how long they will last. They think the life span is at least 300 years, but may be much longer. This makes the specimens an extremely valuable long-term scientific resource. Researchers are finding a vast amount of information contained in the preserved specimens. "We had no idea in 1960 that someone could take a flight muscle from the center of a moth dried on a pin, even one 100 years old, extract and determine DNA sequences, and derive all kinds of information from it," Rawlins explains. Space is needed to expand, and Rawlins calls the process “expansion by curation.” "When you take 100 moths jammed into a drawer (and there are 32 species), by the time you get them all appropriately arranged so that you can find them and curate them, instead of one drawer jammed with moths, you have four drawers," he says. There is also expansion of the collection simply because new bugs are constantly being discovered and added. With 40 percent of the collection housed in what Rawlins terms "unacceptable condition, meaning not housed properly," space continues to be a pressing problem. It is clear that a new storage facility is badly needed, and Rawlins estimates it will be five to seven years before new space is available to finish the job. This new grant affirms NSF's continued commitment to the Carnegie Museum

of Natural History insect collection, and its tremendous importance to

scientific research and education.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All rights reserved. E-mail: carnegiemag@carnegiemuseums.org |

|||