|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

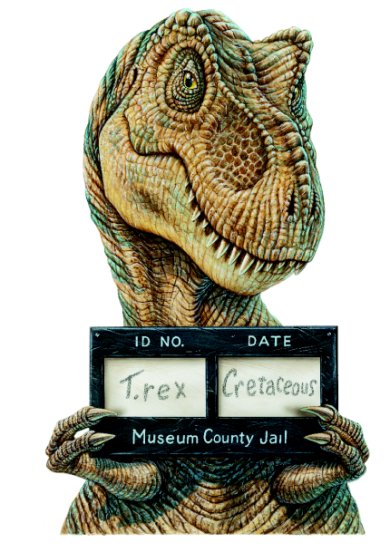

T. rex on TrialJurassic Park Star may have a Padded ResuméBy Merle Jantz

Trial of the Century? Not even close. Trial of the Millennium? A little warmer, but, no. This stuff happened about 65,000 millennia ago. Although in this trial the formal charge against Tyrannosaurus rex, aka Tiny Arms Tony, is murder, in truth the reptile stands accused of not living up to its fearsome reputation as a stone cold killer. Instead of bringing down its victims in a mighty, earth-striding thunderclap of megaforce, this indictment alleges that T. rex cringed in the bushes while some other dinosaur did the heavy work, and then meekly snuck out after this other, nameless carnivore was finished. In short, T. rex was a puny little coward. And out west, where both T. rex and Jack Horner call home, that's worse than being a low-down egg-suckin' dog. Horner, curator of the Museum of the Rockies, at Montana State University in Bozeman, is sending his traveling exhibit, T. rex on Trial, to town this month. T. rex on Trial uses the scientific method to try to determine the facts of the case. Along the way, spectators encounter the methods all scientists use to discover the truth, and hopefully by the end of the day people will be able to come away with some insight about how a scientist works. The exhibit features complete T. rex, Allosaurus and Deinoychus skeleton casts, and other fossil specimens from the Museum of the Rockies' collection, including a pelvis from a Triceratops—T. rex's primary food—with bite marks which may or may not have been made by T. rex. Accompanying the collection are robotic recreations of T. rex, Triceratops, Deinoychus, Tenontosaurus and several more. The idea of the exhibit is to get people thinking like scientists, and

realizing science is not just memorizing a pile of facts, but it's taking

facts and framing them into hypotheses and theories, and then testing them

to see if they hold water. Of all branches of science, paleontology

may be the most like a detective story. Marshal the facts, shape the story

to fit them, test the story. Rarely will you have a smoking gun. Yeah,

it would be a lot easier if the videocameras in the prehistoric 7-11's

could have been preserved, but the Ice Age pretty much wiped out all of

the footage.

Killer or thief? What do experts say?The question isn't a new one, says Zhexi Luo, associate curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. "The debate goes back to 1938," he says, when Edwin Colbert, measuring T. rex trackways, (preserved footprints), posed the theory that the dinosaur moved much slower than was previously thought. About this same time, paleontologist Robert Lang weighed in with an opinion that T. rex’ teeth were not as strong as originally thought. Lang’s theory was refuted by a biomechanical study in a recent issue of Nature magazine, but at the time the combination of weak teeth and a slow rate of speed led to a school of thought that said the T rex did not lead that active a lifestyle. This helped reinforce the notion of it as a scavenger, rather than a predator.

Associate curator Chris Beard thinks the question isn’t black and white. "I think T. rex was probably both (scavenger and predator)," he says. "I think they were pretty much opportunistic." Curator David Berman notes, "I haven’t seen any good published articles proving T.rex was a predator. I think Hollywood has done more to make T.rex a predator than anyone else." What Beard and the other paleontologists like best about the exhibit is not the question, but the process in finding the answer. "You ask the audience. What kind of studies would you do to find this out? How would you reach a conclusion?" Good question. How do you go about reconstructing behavior 65 million years after the fact? One example--the small arms—what for? Mating? Some primitive form of basketball? We really don’t know yet. "We don't even know how sauropods' [plant-eating dinosaurs] feet work," says Mary Dawson, chair of the Vertebrate Paleontology department. "They have a claw, but the claw has never appeared in any of the prints, suggesting that it was retractable. So, when was it used? What for?" "And then tomorrow," she continues, "you find another specimen which

might totally contradict everything you know so far." Since there

are only about a dozen T. rex finds, documenting an animal that was

around for about 20 million years, every new piece of information has the

potential to completely change the way the animal is perceived. "Every

discovery becomes critical," says Beard. "And not just the bones. The bones

mean nothing without the context of where they were found.” Things

like the wear patterns on teeth, stomach contents, what the bones were

found near.

For the record, Dawson leans more toward the scavenger angle. She believes the slow speed theory is reinforced by a later trackway study done by Jim Farlow at the University of Indiana, which suggested that T. rex moved at about 18 MPH, not quite fast enough to run down prey. Also, with unstable hip sockets and a head the size of most people's minivans, "If it falls down it's dead." Thus, she believes the fearsome T. rex was less like a natural born killer, and more like someone with a bad sunburn. A predator? "I don't know, maybe if it came up against a very old, sick triceratops..." she offers. Ouch! Kind of like finding out John Dillinger made all his money by robbing second graders. Vertebrate paleontology is a field of constant discovery, a historical science. "Any kind of science is fun because you're solving problems," says Dawson. "Too often scientists are painted with the wrong brush," she says. "We don't have the last word on a subject. There is never the last word. That's not science." Although dinosaurs are nowhere near her field of interest, 40-plus years in the paleontology business has given Dawson a reason to put so much emphasis on the prehistoric lizards. "People gravitate towards them, and it can be used to interest kids in science." So marveling at towering T. rex may be a kid’s first step down the road of a career in oceanography, pharmacology, or aerospace. The Horner exhibit is designed to be provocative, to stimulate some controversy. "The exhibit teases apart specific functions related to a being predator versus being a scavenger," says Beard. Also fueling the discussion is how the roles of predator and scavenger are viewed through the filter of human perception. We feel a natural disdain for a scavenger, but the fact is, there are very few pure predators in the world today, and many of the animals we associate with predation, lions for example, or bald eagles, are in fact a combination of predator and scavenger. There may be a false dichotomy, Luo says. "It's very seldom either or." And, you know, not to put too fine a point on things, but the next time you find yourself at a fast food place, unless you stalked that cheeseburger and brought it down after an epic battle, why that makes you kind of a... how shall we put it? But enough about you. You're not on trial here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

All rights reserved. E-mail: carnegiemag@carnegiemuseums.org |

|||