The Anthropologist

and the Time Capsules The Anthropologist

and the Time Capsules

By Jordan Weeks

"You should try to keep track of it, but if you can’t

and you lose it, that’s fine, because it’s one less thing to think about,

another load off your mind."

-Andy Warhol

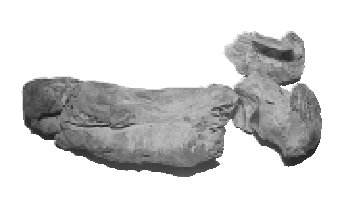

You can see the toes here. It’s probably Egyptian.

It’s been bobbed, too; it’s been wrapped, that’s why it’s not very large.

This part comes up to the bottom of the ankle, where it’s attached to the

ankle. It’d be interesting to X-ray it—you could tell a lot more about

it."

What has Jim Richardson, curator of anthropology at Carnegie Museum

of Natural History, so rapt with attention? Well, among the 600-odd boxes

of Warhol’s personally stored belongings at The Andy Warhol Museum, a mummified

foot was found. Yes, Warhol did have a foot fetish, but…isn’t this extreme?

"Not really," says head Warhol archivist John Smith. "Andy went to a lot

of yard sales and flea markets in New York; we believe it was something

he just picked up there."

"Not really," says head Warhol archivist John Smith. "Andy went to a lot

of yard sales and flea markets in New York; we believe it was something

he just picked up there."

Ah…New York…a flea market. It all begins to come together.

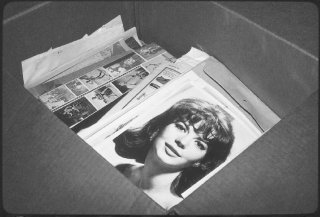

You see, whenever Warhol cleared off his desk, or felt like organizing

a bit, he pretty much put everything into an open box he kept by his desk.

On a regular basis, he would tape the box up, label it with dates for reference,

file it away, and put a new, empty box in its place, ready for the next

month’s sundry accumulations. So far about 100 of the boxes have been opened

and examined. As the archivists at The Warhol have discovered, nearly everything

was fair game for inclusion in these boxes, which Andy dubbed "Time Capsules"…even

the odd, mummified foot.

Richardson and Smith recently examined one of Warhol’s Time Capsules

(or, "TCs" as Warhol called them), and exchanged ideas on the anthropological,

archaeological, and art historical significance of these all-inclusive

boxes.

"We never know what we’re going to find," attests Smith, who oversees

and maintains the entire archival collection at The Warhol, and, when time

permits, joins assistant archivist Matt Wribican in going through the next

Time Capsule with a fine-toothed comb. "Warhol started putting this stuff

together in the 1940s," Smith continues, "and we have no idea where a lot

of it came from. He was saving everything from day one, but then in 1974,

when he was moving from one apartment to another, he and his associates

went out and bought these boxes to accomplish the move. So several hundred

boxes really are a mixture of things, representing different dates and

periods." Smith adds that after Warhol was audited by the Internal Revenue

Service, he became more methodical about keeping his correspondence and

records. At times he would ask an associate to use the boxes for research.

It was a loose filing system for everything in Warhol’s past.

Warhol’s TCs are unlike official "Time Capsules" says Richardson, which

usually conform to several basic rules. Official Time Capsules have pre-determined

"expiration" or "opening" dates, and the items placed in them are chosen

for special historical significance which the capsule assemblers consider

important. The contents of Warhol’s TCs were unplanned, and their future

use was uncertain. "It seemed as if he’d come in and empty his pockets

directly into a Time Capsule," assessed Richardson.

Warhol seemed to place the same significance (or insignificance) on

everything, from articles clipped from newspapers, to checks for $2,000

(a few checks were found uncashed in TCs). He boxed everything from daily

receipts, tickets and letters to the handwritten lyrics for Lou Reed’s

Velvet Underground tune "Heroin," and the used paintbrushes that Salvador

Dali gave him as a present in the late 1970s.

Anthropologists like Richardson focus on "material culture" – the found

artifacts and objects used to assess a society in the absence of a written

history that explains a culture’s politics, religion, or the daily uses

of objects. Richardson says there is no historic precedent for Warhol’s

Time Capsule habit, especially since after the early 1970s it was accompanied

by tape-recorded (and later transcribed and published) diaries, sometimes

explaining in great detail objects that were found later in the Capsules.

It was a tape that identified the paintbrushes as a gift from Dali.

The assemblage of Warhol’s Time Capsules, says Richardson, "is different

because it’s a wide variety of items which are somewhat systematic in their

inclusion, but they are drawn from everywhere, from every venue of Warhol’s

life. In contrast, royal tombs collections reveal that everything has been

prepared and the placed in the tombs." Warhol’s intentions (if indeed

he had any) concerning the preservation of these items is unclear. But

today they fascinate researchers interested in Warhol and the art and popular

culture of the 1940s through 1987—the year the artist died.

Warhol has been described as his own greatest creation. Anthropologist

Jim Richardson’s agrees: "Basically, he collected himself."

The Archives at The Andy Warhol Museum will be closed to researchers

through March 2000 in order to devote time to cataloguing additional archival

material

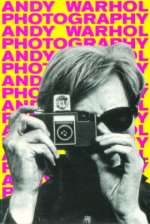

Fame After Photography

January 8 Lecture: Museum Theater, 7pm

In a special program at The Warhol, guest lecturers Marvin Heiferman and

Carole Kismaric, curators of the Museum of Modern Art’s recent Fame

After Photography exhibit, will discuss fame, photography, and the

inevitable intermingling of the two in our culture.

The Warhol’s two current photography shows, Nadar/Warhol: Paris/New

York, and Andy Warhol: Photography, are full of the crosscurrents

of these subjects.

Heiferman says, "Our understanding of fame has been changed since the

invention of photography." He argues that more widespread use of photography

has changed the public perceptions about people and their accomplishments.

"What looks good in pictures begins to define what is good in culture and

society at large."

Warhol and Nadar each emerged from the Bohemia of his day, and both

used photography to create and consecrate a circle of famous people. In

the 1960s-1980s, Warhol, like the famous showman P. T. Barnum, "understood

fame and photography in a broad context, and how the two work together

in a world larger than just the world of images or the world of art." In

addition to portraying people in graphic design, painting and filmmaking,

Warhol used photography to popularize the modern celebrity culture. Nadar,

active in Paris in the 1850s-1860s, added photography to earlier pursuits

as a journalist and caricaturist. He captured in unforgettable portraits

the famous people of his day, such as actress Sarah Berhardt, artists Gustave

Doré and Jean Francois Millet, and writers like Alexandre Dumas

and George Sand.

DIY-burg

Symposium Yields "Do-It-Yourself" Urban Ideas

Last September’s "When You Wish Upon a Star: Themed Worlds" symposium

at The Warhol challenged those who criticize artificially imposed urban

themes and "generic cities" to produce their own creative, feasible, and

fantasy alternatives to the homogenization, and the future "theming" of

Pittsburgh. A basic concern was that the city would try to revitalize itself

by destroying historically significant landmarks that individualize the

city, and replace them with cookie-cutter department and chain stores and

theme restaurants--cheap labor-driven cultural vacuums--that could destroy

the uniqueness of Pittsburgh.

The Edge Architects, and Barry Hannegan, Pittsburgh History and Landmarks

Foundation’s Director for Historic Landscape Preservation, looked at the

city’s past dependence on the rivers, and the current river uses for commerce

and transportation, and conceived of a Venice-like downtown with water

replacing streets in designated areas. Pittsburgh would have water taxis

and buses, floating garages, and floating gardens.

Installation artist Bob Bingham and Quantum Theater founder and producing

director Karla Boos’s proposal focused on the city’s capacity for flora

and fauna, and a desire to "restore the ecosystem with creative reuse of

all buildings and resources." Chatham College electronic art professor

Steffi Domike and video artist Curtis Reaves proposed changing the city’s

infrastructure by adding new inclines, steps, and stairways, repairing

the old ones, and organizing walking and bicycle tours, and photo surveys.

"A place where smokestacks become

poems

and poetry is a game."

Laurie Graham, author of Singing the City, and Christina Springer, director

of Sun Crumbs artists’ organization, proposed a "writing on steel bones"

by means of "The Great Pittsburgh Poem Chase." Lines from a poem about

Pittsburgh, or that incorporate a Pittsburgh theme, would be scattered

about the city at different locations such as the Bayer Clock, billboards,

theater marquees, the trusses of bridges, or the sides of buses.

Poems would be solicited from Pittsburgh poets, and artwork from Pittsburgh

artists.

Each line of the poem would be numbered and participants would assemble

them in an order to "solve" the problem. A reconstructed poem would be

logged onto a website, and if the input provided the right answer, the

person would be eligible for a prize. The Greater Pittsburgh Poem Chase

would celebrate Pittsburgh’s working artists, and would unify life and

art in the city. There would be a new contest each month, and eventually

an anthology would be published. Both Graham and Springer are now hard

at work to realize this project.

The Warhol Community Project, a collaboration between teenagers, architects,

and neighborhood residents, worked with a playful Disney theme and redesigned

the Golden Triangle as a giant theme ride with an Egg Public Transport

system, an egg-shaped, multi-terrain elevator/boat/gondola/submarine. Included

were a Demolition Park where everyone could blow stuff up, and a community

"food court," featuring different ethnic cuisine from the area’s churches

and places of worship.

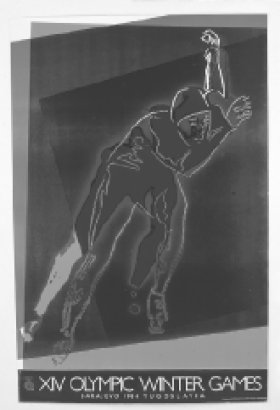

Andy Does the Olympics

Celebrate the Olympics with a rare poster designed by Andy Warhol

for the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics. The International Olympic Committee

commissioned the poster, which captures the energy of a speed skater in

Warhol’s inimitable style. The poster plates were destroyed after a limited

edition printing; only 44 posters remain. Purchase yours for $60 in The

Andy Warhol Museum Store or online at www.warhol.org.

|