|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

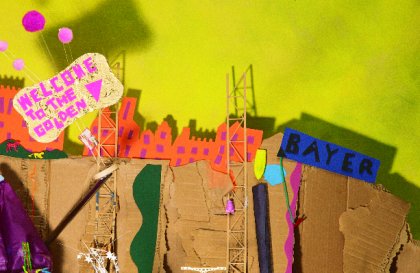

“Pittsburgh as a Theme Park” was the topic for 600 children and adults at the Warhol Museum’s Family Day on July 17 (in conjunction with the current exhibition The Architecture of Reassurance: Designing The Disney Theme Parks). With the help of Steve Beyer, senior concept designer for Walt Disney Imagineering, many people playfully combined “imagination + engineering’ to make a large “Golden Triangle Theme” through the city. Their artwork illustrates this article. During the summer Thomas Sokolowski, the director of The Andy Warhol

Museum, assembled a few of the city’s more visionary thinkers and gadflies,

and invited them to talk about the way Pittsburgh could be themed.

He invited them “not to restrict their thoughts to those meadows of mud

which the bulldozers are now traversing, but to see the city as a totality.”

Theme City: Imagining PittsburghBy R. Jay GangewereIn real cities, dreams come true because the myth of a city, its true identity, is fully understood and appreciated by the marketers who package it for the public. Call it “theming”: creating special places that play to a certain set of values to build pride and promote tourism. Cleveland did it with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, New York City did it with South Street Seaport, and Baltimore did it with Inner Harbor.Director Thomas Sokolowski says The Andy Warhol Museum is the perfect place for uninhibited discussions about Pittsburgh’s themes. “Let the flaming tongues wag as power brokers meet behind closed doors,” he says. He adds: “We should recall that in earlier times great civic leaders like Pericles consulted sculptors and artists about the proper icons for their city, and the Parthenon was the result.” He adds, “We should also remember that ownership is not the same as leadership.” The questions Sokolowski suggests are appropriate to this exploration of theming include: When is a symbol no longer relevant? Should a city that no longer makes steelpromote itself as the SteelCity? How does history get transformed into myth? Does the city’s myth need to be crafted out of popular consensus, or can one voice speak for many? Can different myths collide, and can a city speak with many tongues? Who profits from translating a myth into a real geographic place—from making Pittsburgh’s “story” into a theme park? The ongoing conversation about Pittsburgh’s themes continues here, in this issue of CARNEGIE magazine, with a few selected dreamers: John Dymun, partner, Dymun-Nelson & Co., advertising and public

relations agency;

Sports City?Architect Rob Pfaffmann has a vision for sports fans: make Three Rivers Stadium a sports-themed hotel and lofts, with a vertical urban garden. Stadiums have been saved for centuries in Italy, where Roman coliseums and sports fields have been converted to housing and public spaces. Layering time and place this way can make cities great. Pfaffmann would strip Three Rivers Stadium right down to its massive

concrete and steel rib bones, making a superscaled urban sculpture—or garden

ornament—waiting for new life. On the north end he sees a sports-themed

hotel, with sports lofts for Steelers fans. Everyone looks down on the

outlines of the playing field—-preserved in some park-like way, with monuments

like the Immaculate Reception sculpture, at the very site where Franco

Harris actually caught the ball. The hanging garden would be green with

ivy, trumpet vies, and wisteria, as walkers and joggers used the ramps.

“The embodied energy would be mind-boggling,” says Pfaffmann.

“The embodied energy would be mind-boggling”High-tech roll playingJohn Dymun worked in a Pittsburgh steel mill when he went to college. “It was another world--the scale, the smell, the molten steel, the cranes, the sirens and whistles.”Dymun believes you could translate that powerful experience through high-technology, with 3-D IMAX or virtual reality, to draw people into it today. Visitors could “become the steel, and be poured out of the ladle, and be shaped as an ingot”—-you could be taken on an incredible ride. Dymun also dreams we could take barges--those icons of the industrial age—and use them for large scale works of art, floating, changing, moving. The rivers also offer opportunity: in Toledo, Spain, the river that runs around the city has huge lights directed towards the bridges, which cast magnificent lights and shadows. Charlie Humphrey adds his fantasy of the North Shore as “a kind of ersatz,

industrial park. Just as Colonial Williamsburg has a fake colonial environment,

we would have a fake industrial environment.” A roller coaster coal-car

ride could careen from one end to the other.

Accent the Neighborhoods“Right now the North Shore looks like a blank slate created by demolishing buildings,” says Paul Rosenblatt, “but every site is forever loaded with its past, and some places are more loaded than others.”Famous cities have obvious themes. If you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere. Rome is the city of Christianity, of art and empire. Is Pittsburgh’s dream to be the Steel City forever? Rosenblatt argues that, “the most attractive places are not planned

spectacles with one-day attractions, but rather neighborhoods that are

intimate and circumstantial, that change seasonally and dynamically. One

thinks of walking cities, mostly flat, like Chicago, like New York’s Greenwich

Village, like San Francisco (not flat). They combine residences, shops,

clubs and parks, tree-lined streets, small businesses, and local character.”

Wherever possible, Rosenblatt would continue Pittsburgh’s mix of houses

and shops in an intimate human scale.

“It is important to keep the pedestrian scale—and not destroy the neighborhoods”Find a theme honest to Pittsburgh“If we build a themed-environment in Pittsburgh, it should be organic and be honest to the character of Pittsburgh,” says Humphrey. “In Chautauqua recently, the Disney representatives were there, doing the Disney Institute, and the old-time Chautauqua folks were upset. They didn’t want Disney to take their Chautauqua idea and do it in Orlando—where Disney has already tried to market it without success.”Jeannie Pearlman says making use of the mosaic that Pittsburgh is today is the answer. She says, “Disneyfication is a kind of indictment. I don’t want to celebrate a sanitized view of the past. People died in the mill, people were underpaid all the time, women couldn’t get jobs, and people of color couldn’t get jobs. It wasn’t that sweet.” Chris Potter is wary of artificial attractions. “Like Cleveland’s Rock

and Roll Hall of Fame,” he says, it can eventually be “the butt of local

jokes.” He adds that he’s especially wary of steel-industry themed

attractions that siphon resources away from similar projects in the Mon

Valley, where surviving structures like the Carrie Furnaces confer a legitimacy

that could only be caricatured on the North Side.

The monster in the dream closet: Pittsburgh’s inferiority complex“We suffer from mass hysterical low self-esteem,” says Charlie Humphrey. “We don’t acknowledge something as obvious as our own strong arts community.” This hangover from Pittsburgh’s days as a symbol of urban blight has never disappeared.Pearlman discovered during interviews with steelworkers for an Arts Festival project that “even now, after all these years, there is great bitterness that the steel industry left. There’s still talk about conspiracies, and great anger. It’s very unresolved.” Disconnections make the problem hard to confront. “I know people who

have come to CMU for their MFAs and who have never been out of Oakland,”

says Pearlman. “They don’t engage.” Some days she could wish upon

a star that all the money devoted to cultural tourism could be used to

get the disparate groups to talk to each other--our artists, scientists,

neighborhood people, developers, and government people.

Dream for your grandchild, not your grandparentPearlman says she’s sat at “too many tables where people say, ‘Let’s find a first day attraction! Yet the people I bring here never have time enough to do everything we already have—-from visiting Fallingwater to the Science Center to the Mattress Factory.”Dymun agrees we do not present ourselves well. He remembers the “You’ve got a friend in Pennsylvania” campaign, which was based on solid research. Pittsburgh is very friendly, and it has the things people travel to see: history, natural beauty, culture. Humphrey says, “Pittsburgh has two one-billion dollar foundations, giving money—a lot of it—to arts and culture. They’d kill in Boston to have that. But in Boston they say their city is culturally rich, and it is.” Pittsburgh’s arts community is spread throughout the city, not just downtown in the titular “Cultural Center.” Arts groups are in the South Side, at the Spinning Plate in East Liberty, at the Mattress Factory on the North Side, in Oakland and the East End. “Younger, talented folks do not see the past,” says Dymun. “They

are way beyond the loss of the steel industry. They have energy and

enthusiasm. They believe it can happen here. It’s their attitude.

They’re not dragging around that old baggage. They’re just going

for it. It’s not your grandfather’s Pittsburgh…it’s your grandchild’s.”

Lecture and SymposiumWhen You Wish Upon a Star: Themed WorldsFriday, September 24, Saturday, September 25 Theming a city raises important questions.

How does history get transformed into myth? Does a city’s myth need to be crafted out of popular consensus, or can one voice speak for many? Is the people’s ownership of their story the same thing as civic leadership? Can different myths collide, and can a city speak with many tongues? Who profits from translating a myth into a real geographic place--from making Pittsburgh’s “story” into a theme park? In connection with The Andy Warhol Museum’s current show The Architecture of Reassurance: Designing the Disney Theme Parks, that runs through October 10, the museum is holding a symposium to analyze such questions on Friday, September 24 and Saturday, September 25. Friday evening, September 24 Keynote address by Marty Sklar, vice-chairman of Walt Disney Imagineering, and one of the creative people behind the museum’s current exhibition. Sklar will take a look back at the themed attractions business, from beginning of Disneyland to the new parks opening around the world in 2001. Saturday, September 25, 10am – 4pm

The Factory as Studio and Rec Room - Dr. Steven Watson, writer and critic, will discuss the spaces created by American avant-gardists, focusing primarily on Andy Warhol's’Factory. Art Deco, Cinema and the Theme of the Exotic: Picture Palaces and Picture

Shows

Afternoon Lecture – Pittsburgh as a Themed City – Past, Present and Future – Speaker and Moderator: Paul Rosenblat, architect, assisted by Chris Potter, Editor, Pittsburgh City Paper This will be followed by four presentations by diverse local pairing of writers, artists, filmmakers, architects, and community activists about future visions for Pittsburgh and will close with a panel discussion between presenters and audience. Symposium is free with museum admission. However, seating is limited. Please call 237-8300 to reserve or for more information. Co-sponsored by University of Pittsburgh’s Cultural Studies Program and The STUDIO for Creative Inquiry at Carnegie Mellon University.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||