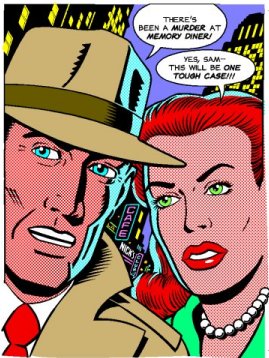

Whodunit? The Science of Solving Crime

Carnegie Science Center—Opening October 25

By Ellen S. Wilson

The hapless short-order cook thinks he got a good

look at the guy. The body in the alley could tell a story, if only

it could talk. And that bloody knife - maybe it's important, maybe

it ain't. What would Sam Spade do? What would Miss Marple do?

Heck, what are you going to do?

The Carnegie Science Center's new exhibit, Whodunit? The Science

of Solving Crime, finally lets you use the crime-solving skills you

always knew you had, and gives you access to the high-tech tools and techniques

the pros use. The exhibit contains hands-on work stations at the

crime scene and in the lab, a film of an autopsy for first-hand results

(detectives can't be squeamish), and other methods for solving the mystery.

So put down that cup of tea, clean-up your magnifying glass, and go nab

the bad guy.

Our story begins at the Memory Diner on Summer Street, the scene of

a recent holdup. You'll know it by the flashing police lights.

Your colleague Detective Ruin is already inside interviewing the short-order

cook, but you know how unreliable eyewitness accounts can be. Or

maybe you don't. Use your own visual memory of the crime scene to

get an idea of how much you can trust what the cook says. Just don't

get distracted like some rookie and miss the news flash about the dead

body in the alley behind the diner.

You rush out to the alley, where an investigator has already done

some of the leg work. There is all kinds of evidence - tire tracks,

a bag of white powder, a knit cap, a partly eaten apple . . . .

How much of it is relevant? Can you assume that the murder and the

robbery are somehow related?

The police have put together enough eyewitness accounts to have three

murder suspects in custody, and one has been caught on video leaving the

diner. Is he the robber? Is the robber the killer? Maybe

the dead guy was the robber. After all, sweetheart, armed robbery

does involve certain risks. And that white powder - are drugs involved?

This could be big. You need some hard evidence. Miss Marble

may have relied on "a certain knowledge of human nature" to solve crimes,

but this here ain't no English village.

The medical examiner at the crime lab lets you watch the autopsy.

Maybe it still bothers you, seeing a dead body opened up like that.

Years of solving crime may have given you a hard edge, a certain toughness,

but once in a while it gets to you. It's okay to look away, just

stick around long enough to hear about the gunshot wound. Does that

mean you can forget about the bloody knife in the alley? Not so fast,

detective.

If you're smart, your next stop will be a visit to the firearms

examiner. One of the suspects, a fellow named Cary Cannon, has a

gun. Maybe you want to know if the bullet found in the deceased matches

one fired from Cannon's gun. Maybe you think you already know.

What are you, some kind of know-it-all? Get the facts.

Fingerprints don't lie. What about the prints on that knife?

On the bag of powder? Cops have been dusting crime scenes for fingerprints

for years, but this new fingerprint scanner, Touchview, makes quick work

of what used to be a big headache. An examination of the DNA from

the blood on the knife can also clue you in as to who stuck who, but don't

go jumping to conclusions. You still don't know the whole story.

You'd better check in with the forensic toxicologist and get the skinny

on what kind of powder is in that bag.

You may think you're getting a pretty good handle on the murder,

but don't forget this whole thing started with the robbery at the diner.

Or did it? The cook may not be a great witness, but unfortunately,

he's the best you've got. Sit down with the Dial-A-Face or use a

computer program to come up with a picture of the robber the cook recognizes.

Surprise, surprise. It's not who you thought it would be, is it?

Looks like you've still got work to do.

You'd better go through the casebooks, look over the police documents,

figure out exactly what you know, and what you don't know. Because

if you don't solve this crime, who will?

Fortunately, there are plenty of experts and new technologies

available for solving crimes when even the most dedicated gumshoeing falls

short. Forensic sculptors such as Betty Pat Gatliff study human remains

and reconstruct a three-dimensional representation of the person they came

from, including such information as race and approximate age at the time

of death. Whodunit includes a video of Gatliff at work, producing

a bust of a corpse found in Dallas, Texas, in 1984, and still unidentified.

Other technologies improve on what investigators

can see with the naked eye. The Polylight produces light frequencies

that reveal normally invisible evidence such as fluids, fibers, or special

inks. Magnification units so powerful they show a person's sweat

pores (the ones that produce the fluids that leave fingerprints) are also

commonly used at crime scenes today. Visitors to the exhibit can

experiment with both of these tools and discover how they work.

Evidence such as teeth, hair, bones, shoe prints,

even the insects found at crime scenes, all tell a story. Learn about

how scientists today detect drug use from hair samples, nab a suspect by

analyzing bite marks, or study skeletons to determine the cause of death.

So is the answer Miss Scarlet in the library

with the candlestick? It's never that easy. But if you narrow

down the options, dismiss the suspects with the watertight alibis and,

above all, examine the evidence, Whodunit will be staring you right in

the face.

Ellen S. Wilson writes frequently for CARNEGIE Magazine.

|