|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Soul of AfricaArt from the Han Coray Collectionby Ellen S. WilsonSoul of Africa: Art from the Han Coray Collection Carnegie Museum of Art May 8 – July 18, 1999Swiss collector Han Coray was one of the first to

In most of the cultures represented in Soul of Africa: African Art from the Han Coray Collection, "good" and "beautiful" are expressed by the same word. Han Coray, a Swiss educator and art dealer, assembled his extraordinary collection in the early 20th century on aesthetic grounds. The people for whom these objects of African art were made, however, did not separate beauty from function and meaning. The aesthetic qualities of a chair were part of its purpose – not only to provide a place for a leader to sit, but to indicate his rank and importance, to honor him, to bring him and his people good fortune. Han Coray was the first person in Switzerland to exhibit African tribal objects as art, and 200 pieces from his collection of West and Central African works reveal the high quality of his collecting. Coray associated with such rising young artists of the Dada movement as Hans Arp, Marcel Janco, Tristan Tzara and Hans Richter, who gathered regularly at his gallery and were undoubtedly influenced by what they saw there. Traditional forms of Western art no longer seemed meaningful to these artists. The small wooden sculptures, fabrics, masks and other pieces that Coray collected in great quantities – more than 2400 in all – had a completely unfamiliar look that became so important we can see its effect on much of the Western art produced following its arrival in Europe in the early 20th century. And yet there are telling differences. Contemporary artist Georg Baselitz (whose work was featured in a major exhibition at the museum in 1998), has assembled his own collection of African sculptures over the last 20 years. Baselitz comments on the remarkable consistency in African art in his exhibition catalogue essay about the Han Coray collection: "The basic pattern remains unchanged," he writes, and no individual artists are known by their work. While this is unusual for viewers used to European or American art, and the attendant personalities of the artists, Baselitz finds a corollary in "legends that have come down to us by oral tradition from the distant past." If the purpose of a piece remains consistent, so must the piece's design.  The exhibition is organized into six thematic areas: Art and Leadership, Rank and Prestige, Music in the Service of Spirits and Kings, Communication with the Supernatural World, Remembering the Dead, and Life Transitions. Because this collection was put together before there was any active tourist market for African art, the quality of the pieces is very high. Formal perfection was quite important to African artists, and the more crudely produced items we sometimes see today were generally made for tourists rather than for ceremonial or even daily use. Although Coray's criteria for his collection were primarily aesthetic,

the context surrounding the works does help a modern viewer appreciate

them since, as Baselitz writes, "There is a connection between the idea

behind a sculpture and its designated purpose." In the museum, these

pieces are out of context, removed from their natural life cycle, as any

decorative arts piece exhibited in a museum would be.

Similarly, power figures were altered after their completion by the sculptor through the addition of substances thought to contain supernatural powers, or by nails that were driven into them to activate healing powers, elicit advice, or seal an oath. Figures such as these could be "used up" to the point where new ones had to be produced. And while the objects themselves are not particularly old, they represent art forms that are many centuries old. Some pieces, such as special stools and thrones, convey the authority

and status of the owner through their imagery, the material

used, or the exceptional craftsmanship. A throne carved in

the shape of a leopard was intended to associate the qualities of this

animal -– strength, cunning, speed – with the leader who used it.

While it is obvious that great pains were taken in the carving as well

as the superficial details of the leopard, it is not an attempt to

reproduce nature in realistic detail.

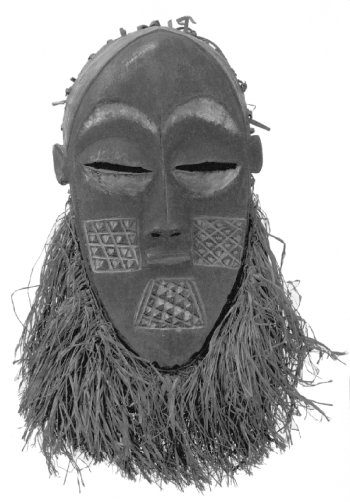

Exhibition curator Miklós Szalay says Han Coray came to believe there was no distinction between African art and religion. Death is a transition to a higher realm, and representations of deceased ancestors are meant to encourage their participation in the lives of those they left behind. "The masks and headdresses used in public ceremonies often represent specific people who have passed on and are now engineering the future of the community at large," Csorba explains. "Every distortion, every expressionistic feature conveys the unseen world, the more powerful world." Szalay goes on to say that today, the unity between art, religion and society no longer exists in Africa the way it did in the 1920s. "Art, it is said, strives for autonomy," he writes in the catalogue, but then cautions that as art is released from its social and religious context, its importance is diminished.  How fortunate for viewers today that Coray formed his collection

when the bonds between art and spirituality were so strong. The Baule

carved, in addition to the wilderness spirits, spirit spouses known as

blolo bian ("other-world man") or blolo bla ("other-world woman").

Every man, according to the Baule, has a female component of his soul,

and every woman a male component. To appreciate these small wooden

figures, they must be seen as concrete embodiments of this concept, capable

of jealousy of the earthly mate, of causing sterility or, if appeased through

offerings and devotion, of insuring fertility. The statues were touched,

caressed and cleaned, presented regularly with food and, according to Csorba,

were meant only for private viewing. Seeing them in this spiritual

context, they gain both power and beauty.

Ellen S. Wilson is a frequent contributor to Carnegie Magazine. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||