|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Life & Death in the MesozoicBy Kathryn M. DudaCarnegie Museum of Natural History reflects the latest discoveries by incorporating them into its exhibits and programs. Gone is the old, scientifically incorrect T.rex wall painting in Dinosaur Hall, replaced by an accurate and visually stunning mural nearby. The hall features a dramatic sound and light show every hour, a robotic tour guide, and interactive computer games. You can examine a fossil that flew aboard the space shuttle in 1998, watch scientists extract fossils from a bed of rock, and see a replica of the largest flying animal ever known to exist. In March, a world-renowned scientist speaks about the end of the dinosaur era, and this summer we’re installing a life-sized model of Diplodocus on Forbes Avenue. This is the place where dinosaurs come back to life. Walter Alvarez Explains the “Crater of

Doom”

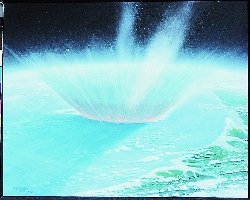

In the early 1990s, scientists announced a startling theory: Dinosaurs, and many other life forms, perished as a result of a giant asteroid that crashed into the Earth 65 million years ago.  Geologist Walter Alvarez was at the

forefront of the research that led to this astounding theory. Over the

course of two decades, Alvarez pursued the question of the dinosaurs’ demise,

making discoveries of his own and synthesizing those of other scientists.

His theory is this:

But as compelling as it is, the Alvarez

theory is not accepted in all scientific circles, especially among vertebrate

paleontologists—scientists who study the fossil remains of animals with

backbones, including dinosaurs.

So why did the Mesozoic dinosaurs all die

out around the same time? Dawson offers two theories: because of a climatic

cooling (unrelated to the meteorite); or perhaps because of the proliferation

of flowering plants, which have a different biological make-up than the

plants herbivorous dinosaurs fed upon.

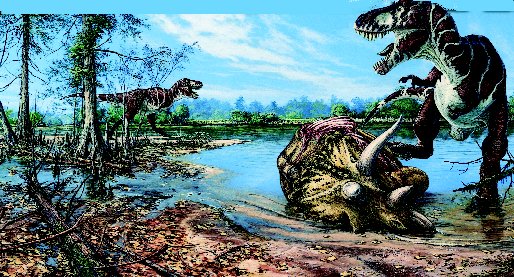

Member TipAlvarez’ riveting tale is explained fully in his book, T.rex and the Crater of Doom, on sale in the Natural History Store. Use your member card for a 10% discount!New Mural Shows T.rex in a New LightScientists are agreed: theropods—-two-footed carnivores like T.rex--are ancestors of modern birds. And that theory has led to new insights about the biology of theropods—scientists are now rethinking how these stood, moved and ate.Some of these recent discoveries are reflected in the new mural in Dinosaur Hall, a dramatic color rendering by Michael Skrepnick, one of the most sought-after dinosaur artists in North America. In the Skrepnick mural, T.rex assumes the more horizontal posture that we now believe to be correct. “The horizontal posture is considered more accurate because new studies of the T.rex skeleton show this is how the bones fit together,” says Carnegie paleontologist Chris Beard. He says the biggest advance in showing that T.rex walked horizontally is the theory that theropods are related to birds. “The new posture of T.rex is not different from that of a blue jay at a bird feeder,” he adds. Half a century ago, scientists didn’t know that theropods were related to birds, and they thought the bones fit together another way, resulting in a vertical stance. “That tells you there’s some flexibility” in thinking about various aspects of dinosaur biology, Beard says. The natural surroundings of T.rex are on

display as well, as the mural shows what scientists now believe to be an

accurate portrayal of eastern Montana 66 million years ago. It was a sub-tropical

coastal plain in those days, with an inland seaway called the Cannonball

Sea that extended from the Gulf of Mexico up into Canada. Look closely

and you’ll see something familiar--a pond turtle, the artist’s reminder

that some dinosaur-era flora and fauna are still part of the Earth’s biodiversity

today.

Largest Flying Reptile: QuetzalcoatlusThe largest animal that ever flew--Quetzalcoatlus northropi—has landed at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. With a wingspan of 36 feet, this gigantic pterosaur now hovers high above the dinosaur specimens like it did in the late Cretaceous period some 80 million years ago.The model features a skeleton cast with a muslin covering that gives visitors an idea of the animal’s imposing wingspan. Visitors can immediately understand that T.rex was not by any means the only big player during the Cretaceous. Carnegie paleontologist Mary Dawson says the skeleton from which this model was cast was a rare find, because Quetzalcoatlus bones are fragile and are rarely discovered in good condition. Carnegie Museum of Natural History is the first to exhibit a complete specimen in a flying posture. The extensive restoration work done on the original skeleton for this project has caused scientists to take another look at how pterosaurs flew, Dawson says. “They’ve discovered that these creatures flew differently than birds do, with the wings supported by an elongated finger. Also, pterosaurs probably used their wrists to fly,” she adds. It is possible that more information on pterosaur flight will be uncovered as scientists continue studying this specimen. Quetzalcoatlus northropi was found in southern Texas on the Canonball Sea, the same waterway at which T.rex is shown in the new Dinosaur Hall mural above.

Look for Our Dinosaur on Forbes AvenueDiplodocus carnegeii, the giant 12-ton dinosaur whose fossil bones made Carnegie Museum of Natural History famous, is going to step outside the building and show itself in the flesh. Or at least in fiberglass. A life-size replica, about 90-feet long and 15- to 18-feet high at the hips, will be installed this summer at the corner of Carnegie Institute and Library near Forbes Avenue and Schenley Drive. Oakland will get an unforgettable one-of-a-kind landmark that symbolizes the great changes taking place at the museum.Called “Dippy” by Andrew Carnegie’s friends, Diplodocus has been the museum’s signature exhibit ever since Andrew Carnegie had the fossil bones that were discovered in Wyoming in 1899 delivered to Pittsburgh and mounted in his new museum. Carnegie enjoyed presenting casts of Diplodocus to museums around the world. He boasted about America’s scientific progress, and his own institution’s pre-eminence in research. In 1904 he honored the King of England’s request to have one at the British Museum, and he kept on giving to presidents, kings and emperors, for installation in other national museums. By 1913 he had given replicas to natural history museums in Germany, France, Austria, Italy, Spain, Russia and Argentina. Mrs. Carnegie sent a replica to Mexico in 1930, and another set of cast bones was sent to Munich in 1934 (but not erected). The casts were re-used to make molds for Dinosaur National Monument in Utah, but by then had reached the end of their useful life. As far as we know, the fossil skeleton of “Dippy” is still a must-see exhibit in nine of the world’s greatest natural history museums. Science now has new information about the behavior of Diplodocus. “Dippy” is thought to be a browser of understory plants, so our replica’s neck will be more horizontal than before. The long tail probably balanced its long extended neck, and so the tail will be raised off the ground. The bronze-colored giant who greets the public on Forbes Avenue will be the most lifelike Diplodocus science can create. --R. Jay Gangewere

|