|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

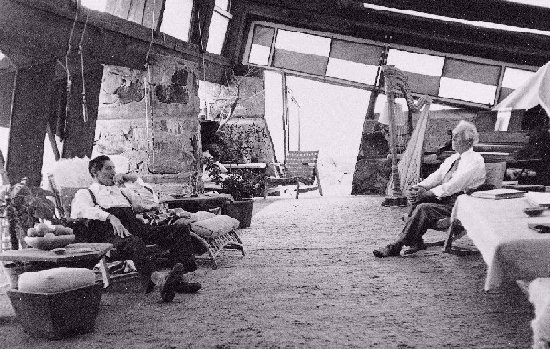

Merchant Prince & Master BuilderFrank Lloyd Wright Edgar J. Kaufmann |

|

|

|

|

|

| Frank

Lloyd Wright’s rapidly-done sketches for Fallingwater were a wonderful

tour de force of architectural drawing under pressure.

As one of Wright’s admiring apprentices, Edgar Tafel recalls it, Wright was at his Wisconsin studio on September 22, 1935, when he got an unexpected call from Edgar Kaufmann, his impulsive client and the owner of the Pittsburgh department store. Kaufmann was in Milwaukee a few hours away, and announced he was driving out to see Wright’s progress on the drawings for the summerhouse at Bear Run, Pennsylvania. “Come right along E.J., we’re ready for you,” Wright said. At that moment he had no drawings of Fallingwater.

Always resourceful, the 69-year-old architect gathered his colored pencils, went to the drafting board, and while admiring apprentices watched, rapidly drew the plans of a house that became an icon of American architecture. As fast as his pencils wore out or broke, he reached for new ones. His style when drawing was to deliver running commentaries about the clients. For Kaufmann he knew what was needed. “The rock on which E.J sits will be the hearth, coming right out of the floor, the fire burning just behind it. The warming kettle will fit into the wall here… Steam will permeate the atmosphere. You will hear the hiss….” Virtuoso matchmaking between a client and his house was Wright’s forte, and he finished his drawings shortly before Kaufmann arrived at his front door. During the leisurely lunch and discussion of his designs, his apprentices Edgar Tafel and Bob Mosher worked up additional elevations. When Kaufmann left, satisfied but doubtless adjusting to the fact that his house was directly over the waterfall, and not positioned to view it from a distance, he had his architectural plan. The plans for Fallingwater were not a spur-of-the-moment exercise. As usual, Wright privately nurtured his thoughts about his client’s needs—and in this instance even named the house. Wright’s principles of organic architecture had been perfected over a lifetime of work, and biographer Meryle Secrest says Fallingwater was “the fruit of a mature creativity and a deeply felt aesthetic.” The house rapidly became a symbol of modern architecture, its basic design unchanged even as it was refined from drawings to final construction during 1936-38. Created in the midst of the Great Depression, the woodland retreat over the waterfall had a fast track into the American psyche. It was a personal escape into nature, produced at a time when Hollywood was creating escapist fantasies of its own about avoiding economic hardship. Millions of Americans, including unemployed workers in western Pennsylvania, could dream about life in a private retreat created by the most famous architect in America. National magazines loved Wright’s daring

design and his organic principles. Publicity was immediate. In January

1938 photographs were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and then published

in Architectural Forum. Time ran a feature story describing the house.

The appeal of Fallingwater never diminished. After his parents died,

Edgar Kaufmann jr., who had studied at Taliesin, began considering how

to make the family retreat a public showcase of Wright’s high-concept architecture.

He asked Wright to design an entry building to the property, and in 1963

he turned it over to the non-profit Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

In doing that, Edgar Jr. revealed his own flair for taking good design

to the public, just as his parents did so deliberately in the department

store.

A Unique Client/Architect RelationshipThe 25-year association between the Kaufmann family and Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the most remarkable client/architect connections in American architecture. Edgar Sr., his wife Liliane, and his son Edgar jr. shared Wright’s conviction that good design could transform the lives of those it touched. Edgar Sr. had a ready supply of cash in the midst of the Great Depression, and liked to turn architectural visions into realties. Wright, an aging and cantankerous genius whose family motto was ”Truth against the world,” seemed to some observers near the end of his long, productive career as he approached 70. But Kaufmann was a great client, and knew the price of working with genius. Their friendship survived the conflicts of two powerful men each capable of manipulating the other. The day before Kaufmann died in 1955, he and Wright were still planning architectural projects.Merchant Prince and Master Builder brings

together for the first time 49 drawings and models which reveal this fruitful

client/architect relationship. Dennis McFadden, curator of the Heinz

Architectural Center, says that all three Kaufmann’s--father, mother and

son--were very creative individually, and artistically adventurous in returning

to Wright over and over again with new commissions “to give form

to their aspirations for their life, their business and their city.”

The exhibition establishes Wright’s work here as another reason for tourists

with architectural interests to visit Pittsburgh.

McFadden’s co-curator of the exhibition, architectural historian Ricchard Cleary of the School of Architecture of the University of Texas at Austin, has produced for the exhibition the definitive catalogue of the dozen projects which Wright created for the Kaufmann family. Only three were built (Fallingwater, its guest house, and Kaufmann’s office), but the drawings include some of Wright’s most visionary schemes for urban redevelopment. Most of the original drawings in the show are from the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives in Scottsdale, Arizona, and have never been exhibited before. Edgar jr. studied at Taliesin, and Fallingwater captured their family’s need for a summerhouse, but the Kaufmann’s lives interacted with Wright’s in other ways. The Kaufmann’s marriage was troubled, and Wright’s designs had a recurring role in keeping harmony within the family. Edgar jr. and Liliane commissioned Wright to design a place of spiritual meditation at Bear Run--the Rhododendron Chapel--but it was never erected. Shortly before Liliane’s death at Fallingwater from an overdose of sleeping pills, Wright was engaged in designing a home for her: “Boulder House,” in Palm Springs, California. Edgar and Liliane were cosmopolitan, forceful,

and stylish. They brought to Pittsburgh the latest ideas and fashions they

saw on their travels in Europe. They also were first cousins. Intermarriage

was a dynastic tradition going back for centuries in the Kaufmann’s German-Jewish

ancestry, according to professor Franklin Toker of the University of Pittsburgh.

Certainly marriage consolidated family ownership of the store, and together

they promoted the store’s importance to the city. Liliane enjoyed

an independent life of her own. She created the high-style Vendome

Shops on the eleventh floor of the store, reflecting the elegant Place

Vendome in Paris, where they enjoyed staying at the Ritz Hotel. She was

also an important leader in the hospital community, for years the head

of the board at Montefiore Hospital and later a promoter of Mercy Hospital.

Design and world affairs intermingled in their lives. They assisted Jewish friends in Europe in immigrating to the United States to escape the anti-Semitism before World War II. They knew artists and intellectuals (Physicist Albert Einstein stayed at Kaufmann’s house in Pittsburgh when he first immigrated to the United States.) The family was part of a small Pittsburgh community of collectors of avant garde art at a time when abstract art was not welcome at all museums, and Fallingwater, an extreme example of reinforced concrete architecture, was a complete rejection of the traditional idea of a European manor house in the country. Kaufmann’s taste for sculptures, paintings and houses was years ahead of its mainstream acceptance by many collectors and museums. Selling Good DesignEdgar Kaufmann, one of the most creative of storeowners, was a constant advocate of Modernism in style and technology, and in merchandising good design. “Good forms sell much better and cost no more. The work of the artist hasbecome profitable both in industry and business.” So argued Paul Frankl, leader of the American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen, and a friend of Kaufmann’s. Needless to say, Kaufmann brought him to Pittsburgh to lecture. The store held exhibitions, brought distinguished lecturers to the city, and celebrated events such as Lindbergh’s trans-Atlantic flight (thus attracting 50,000 visitors in one week). After the trend-setting exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Art in Paris in 1925, Kaufmann’s staged its own International Exposition of Industrial Arts, featuring examples of great design from periods throughout history. Replicas of the ancient bronzes at Carnegie Institute were borrowed for the display. Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture was part of this ongoing scenario to promote good design in Pittsburgh. In 1935 Kaufmann’s store exhibited Wright’s model of “Broadacre City,” a visionary plan for a decentralized community (a “disappearing city”) with farms, businesses, and public buildings. New building materials and furnishings were shown along with information about home financing to give the average person a new approach to housing. But Mayor William McNair of Pittsburgh called it “pure socialism,” and “a town built for a lot of social workers.” Controversy probably fueled attendance. A Vision of PittsburghInevitably Kaufmann drew Frank Lloyd Wright into his urban renewal plans for Pittsburgh. As a civic leader Kaufmann envisioned a rebuilt downtown core, and during the 1940s he advanced the work of the new agencies to create a “Pittsburgh Renaissance.” Wright responded to the challenge to redesign downtown with a megastructure at the point, incorporating everything a city center needed: sports, theater, opera, gardens, retail, parking, fountain, aquarium, a marina…all easily accessible by automobile. He called his 1947 design, “Point Park Coney Island in Automobile Scale,” and he described the structure as “a good time place, a people’s place.”Pittsburgh decision-makers in business and engineering were intrigued but not convinced. Wright’s plans welcomed the automobile age with giant bridges, ramps, and parking facilities—but in later decades monstrous parking garages of reinforced concrete turned out not to be the salvation of cities. Wright also designed new housing for Mt. Washington, and a circular parking garage (looking somewhat like the Guggenheim Museum in New York) next to the department store. None of these was built, despite the time, energy and money spent on them. Wright periodically chided Kaufmann for

never following through on these plans, but they were fundamentally different

from the successful collaboration at Fallingwater. The summerhouse

was a comparatively minor feat, totally under Kaufmann’s control.

It hardly mattered that in the 1930s it was projected to cost about $30,000

and eventually cost over $70,000. Kaufmann could pay for it.

But the Pittsburgh designs a decade later were vast government projects

involving private support, official agency approvals, and tens if not hundreds

of millions of dollars of investment.

Many of the ideas of the time took other forms. Kaufmann once proposed to Wright that he design a planetarium next to the department store. It did not happen, but a few years later Buhl Planetarium was built on the North Side, a project of the Buhl Foundation. The open air Civic Light Opera space that Kaufmann wanted in the Point Park megastructure eventually became the Civic Arena, for both entertainment and sports. Point Park became an historical park—contrary to the Wright-Kaufmann development idea. But Point Park today has a performance space, and in its way is “a people’s place.” In the 1950s the brilliant client/architect relationship ended. Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann separated, and Liliane died in 1952. Newly remarried, Edgar’s health failed, and he died in California in 1955. Edgar jr. cultivated the beauty of Fallingwater by himself, but increasingly saw it as a public treasure under his stewardship, and he gave it to the public eight years after his father’s death. During a speech Edgar jr. gave at Carnegie Music Hall, he remembered that when he was young he saw the giant plaster façade of St. Giles in Architecture Hall at Carnegie Museums, and that had made an unforgettable impression on him. He never forgot that you could give architecture to people, and that it could change their lives. It was equally a controlling idea for Edgar Sr., for Liliane, and for Wright, and it is on display in Merchant Prince and Master Builder. -R. Jay Gangewere SourcesRichard Cleary’s Merchant Prince and Master Builder: Edgar Kaufmann and Frank Lloyd Wright (The Heinz Architectural Center, 1999) is the definitive treatment of this subject. Especially helpful to me was information shared by Professor Franklin Toker of the Fine Arts Department of the University of Pittsburgh. Other sources included Edgar Tafel’s, Apprentice to Genius: Years with Frank Lloyd Wright (New York: McGraw-Hill Company, 1979); Meryle Secrest’s Frank Lloyd Wright ((New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1992); and Edgar Kaufmann jr.s Fallingwater, A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House (New York: Abbeville Press, 1986). Edgar Kaufmann’s life is summarized in Leon Harris’s Merchant Princes (New York: Harper and Row, 1979).

|