|

||||

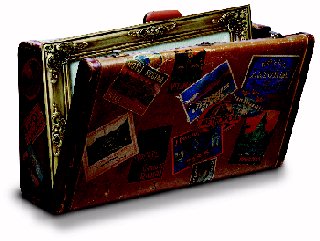

| to Europe for a two-week research trip

with Susanne Ghez, a member of the 1999 Carnegie International’s

Advisory Committee. Together, we visited Glasgow and Edinburgh, Scotland;

Derry, Northern Ireland; Copenhagen, Denmark; Malmö, Sweden; and London.

At that time I was one year and one week into my tenure as curator of the

1999 Carnegie International.

For a contemporary art curator, there is

no greater excitement or challenge, and perhaps no greater privilege, than

organizing the latest installment in this 100-plus-year-old exhibition

series. Every few years, Carnegie Museum of Art presents the International

as an aesthetic and intellectually acute statement on the art of our time,

a statement that does not merely reflect on, but also influences the present

cultural moment. In the United States, the Carnegie International is the

most significant vehicle through which the public, expert and novice alike,

reaches a consensus on the current state of art.

Early on I devised a method for planning my research trips abroad. My itineraries usually revolve around a major exhibition, which allows me to see the work of many artists in short order, and around which I then build a series of studio visits with artists. Having picked my geographical target area, I follow up with a month or more of in-depth research into local galleries and museums, garnering advice from colleagues about artists of interest. Perhaps most crucially I arrange for a local guide to accompany me to studio visits (particularly in countries where I do not speak the language). Often these guides—young fellow curators—provide me with a crucial perspective on the community I am visiting, and by the end of the trip we have become friends. In this way I have thus far visited 27 countries and over 200 studios. My list of artists is taking solid shape, and the thematic threads that will bind the show are likewise beginning to reveal themselves through the artwork I am seeing. In March 1997 it was symbolically significant to me that my first research trip took me to Los Angeles. While New York remains the center of American art commerce, Los Angeles has risen as a center of American art creativity, and it is home to some of the very best visual artists in the United States. I also wished to acknowledge that while the Carnegie International has an enduring commitment to art worldwide, it is a necessarily American project, with a primarily American audience, and organized by an American-trained curator. From the beginning I felt that if remained sensitive to my cultural and geographic base here in Pittsburgh, USA, and to the capacities as well as the limitations of that viewpoint, I could proceed to organize an international survey from an admittedly subjective but also highly informed position. My position as curator would become tenuous only if I claimed to be free of geographic and cultural biases. The most important element in my research would be to remain open and flexible to the artwork I would see. May 1997 found me in Havana for the seventh Cuba Bienal, which since 1984 has focussed on the art of the so-called “Third World”— Central and Latin America, and Africa. This was the first of a staggering seven international survey exhibitions that I would see in 1997, including Germany’s Documenta, the Münster Sculpture Project (Germany), and the Venice Biennale in June; the Lyon (France) Biennale in August; and the Johannesburg (South Africa) and Istanbul (Turkey) Bienniales in October. Indeed, 1997 was a banner year for large-scale international exhibitions both in their number and in the consequent examination of their origins, purposes, and current structures. The function and even legitimacy of international exhibitions are being questioned today as never before. As a result, these shows have gone beyond such traditional organizing formats as presenting artists by their nationality (as in the Venice Biennale) having a single curator make the selections. More recent international models have used a team of curators who share authority for the selection artists, thereby incorporating multiple and even contradictory viewpoints in process. The resulting exhibitions (or conglomeration of mini-exhibitions) tend toward a multifarious and multinational presentation that is a curatorial equivalent to our globally diverse moment. The increased activity in international exhibitions has had the curious effect of making the Carnegie International seem exceptional, even vanguard. What differentiates this exhibition is, paradoxically, its traditional structure: it is curated by a single vision with the active advice of an international committee of art experts, and it modest in size relative to some of its newer counterparts. Consequently, this show can distinguish itself with a strong artistic focus and thematic cogency, those elements that are difficult to achieve in larger, more unwieldy undertakings. At the same time, the Carnegie International will always be distinguished by its longevity, its many manifestations serving as models for other shows of its kind. This was made clear to me in August 1997 when, in Bellagio, Italy, I attended a meeting of international curators organized by Arts International and sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation. All curators present were either in the midst of or fresh from organizing international exhibitions in Australia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Cuba, Italy, Senegal, South Africa, Turkey, and the U.S. On the second day I was approached by a curator who expressed surprise that I was a fellow conferee; rather, as a representative of the Carnegie International, he had assumed I would act as an advisor to the other curators who were in charge of less senior projects. This comment sent a clear message as to the importance and respect with which the International is held worldwide. I learned a tremendous amount from my curatorial

colleagues at that conference, and their comments clarified for me the

role of the international at the end of the millennium. With the greater

degree of global communications, an escalating interdependent international

marketplace, and an ever-growing ease of movement among art-world participants

(especially artists), the definition of “international art” is undergoing

rapid change. As the artist’s frame of reference is increasingly shared

worldwide by his or her peers, “new internationalism” is emerging in which

artworks combine global vocabularies with the artist’s local influences.

And whereas a decade ago the art world’s makers and exhibitors were in

the Western world (a perusal of the 1988 Carnegie International catalogue

makes this vividly clear), today the art world is at its most decentered,

with thriving communities based in such formerly outlying geographies as

Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Scandinavia, and cities such as São

Paulo, Seoul, and Vancouver. These changes in the art world will be reflected

in the selections made for the 1999 Carnegie International.

I began 1998 on a high note, by inviting Willie Doherty to participate in the International while I visited him in Derry, Northern Ireland. Before sitting down in his studio to see a selection of his videos and photographs, Willie took me on a walk through his hometown. I was struck by the way Derry’s cityscape spells out the historic and present conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. Doherty’s work addresses with great passion and intelligence specific and urgent issues—yet as grounded as his work is in a particular locale, it speaks volumes about universal conditions. Willie Doherty’s work carries out one of the most serious functions of art: to give definitive visual expression to the most important debates of our time. May 1998 was a particularly gratifying and productive month for the Carnegie International, as the Advisory Committee met for the first time in Bellagio, Italy. Three of the foremost curatorial talents worldwide joined me and Carnegie Museum of Art director Richard Armstrong for three days of intensive discussions around the themes of the International. Okwui Enwezor, Nigerian poet, critic, and curator, will organize the next Documenta exhibition in 2002. Susanne Ghez is director of the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, and is well known for her prescient work with emerging artists who have gone on to become important creative forces. Since Lars Nittve joined the committee in January 1998, he has left the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark to become the director of Modern Art at London’s Tate Gallery, Bankside, where he remains one of the most vital curators working in Europe. These three colleagues have helped to refine the vision for the International in immeasurable ways. Encouraged and inspired by their advice, I proceeded from Italy to Israel for an in-depth week of studio visits in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. In July 1998 I traveled to Japan, Korea, and Taiwan for three weeks. Even with Asia’s sobering economic circumstances, there was strong new work to be seen, particularly in painting and photography. A dedication to traditional forms of art production, combined with a taste for popular and even garish everyday culture, was a common strain in the work of the three countries I visited. Seeing the second Taipei Biennial in Taiwan provided me with the opportunity to study a concentrated grouping of artworks from Asia that deepened my perspective on the region. I conclude this journal , in October 1998, finding myself once again on a plane, this time to Luxembourg to see the second Manifesta, an “itinerant” biennial devoted to emerging artists that takes place in a different European city every two years. From there I travel to Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Basel, Zurich, and London, all in the course of ten days. A visit to Latin America in November 1998 and a trip to China and Thailand in January 1999 will bring my extensive travels to a close. Spending as much concentrated time as I have speaking with artists and colleagues around the globe has been an enormously edifying and gratifying experience. The International will undoubtedly reflect their keen visions and generous observations. This undertaking has clarified for me the role of the curator. Once primarily a scholar and arbiter of taste, the curator today is more likely to be a conduit and catalyst for the creation of art and the engagement of the public. The curator is a facilitator who helps engage artist and audience in an open-ended conversation through which is argued over, made, and remade. For artist and audience alike, the Carnegie International remains a way to think in visual form about the present, a forum where is not only raised, but also shaped. -Madeleine Grynsztejn

The 1999 Carnegie International is sponsored

by Mellon Bank.

|

||||