"Nowadays if you're a crook you can write books, go on TV, give interviews—you're a big celebrity and nobody even looks down on you." (1)—Andy Warhol

"In the original photograph I was working from, Pol Pot's face looked smooth and calm. ...I wondered how he could look so pleasant yet treat people so cruelly."

—Former Khmer Rouge prisoner Vann Nath (2)

Almost

a century before O.J. Simpson of Brentwood, California, there was Harry

K. Thaw of Pittsburgh. Born to a wealthy family in 1871, Thaw was an idle

spendthrift best known for his bizarre sexual appetite and his marriage

to Evelyn Nesbit, a beautiful chorus girl who had once been the lover of

architect Stanford White. That last fact came to obsess Thaw, and on June

25, 1906, during a musical revue at Madison Square Garden — which White

himself had designed—Thaw shot the architect dead in front of hundreds

of witnesses. "He ruined my wife," he later explained to police.

Almost

a century before O.J. Simpson of Brentwood, California, there was Harry

K. Thaw of Pittsburgh. Born to a wealthy family in 1871, Thaw was an idle

spendthrift best known for his bizarre sexual appetite and his marriage

to Evelyn Nesbit, a beautiful chorus girl who had once been the lover of

architect Stanford White. That last fact came to obsess Thaw, and on June

25, 1906, during a musical revue at Madison Square Garden — which White

himself had designed—Thaw shot the architect dead in front of hundreds

of witnesses. "He ruined my wife," he later explained to police.

The story had everything—a beautiful woman, fame, the titillating sex lives of the jaded and wealthy—and people all over the country found themselves warming to Thaw after it became public that White himself was something of a cad. The subsequent trial was a sensation attended by thousands of fascinated onlookers. "One evening his adoring crowd offered to rush the jail to rescue him," reports author Michael Mooney, "but Harry appeared on the second-floor balcony and spoke to them, calming their fears for his safety." When Thaw returned to Pittsburgh as a free man in 1915, he was met by a crowd of 1,000 who conducted a triumphal parade to his family home.

Thaw died in 1947, but he took at least one secret to the grave with

him, the only real mystery surrounding the murder he committed: How had

so many law-abiding people become so fanatically devoted to a man writer

Cleveland Amory described as a "sadistic pervert," a man whose only distinguishing

act was to murder one of the country's greatest architects? It took more

than 60 years to find an answer, and the solution only came when yet another

criminal scandal linked yet another prominent architect with yet another

famous Pittsburgh son—Andy Warhol. Warhol's solution—along with corroborating

evidence from seven other artists—will be on display at The Andy Warhol

Museum in the exhibit In Your Face.

Eminent architect Philip Johnson, who had designed the New York State

pavilion for the 1964 World's Fair, commissioned Warhol to provide a mural

for the structure's outer wall. Warhol had unveiled his trademark images

of trademark brand names just two years before, and no doubt would have

made everyone happy if he had just stuck to soup can labels.

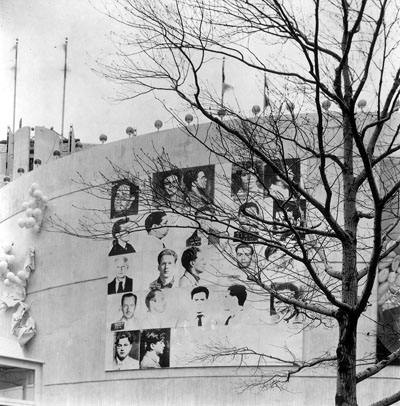

Instead he submitted "13 Most Wanted," a 20 foot-square work featuring 13 mug shots from the FBI's "Most Wanted" lists. Fair organizers were mortified: among Warhol's subjects were a significant number of Italian Americans who'd been accused of ties to organized crime—sure to anger visitors of Italian descent. And wasn't Warhol celebrating notorious criminals? Were these the emissaries America wanted to represent it at the World's Fair?

The mural was censored, painted over in silver before the fair even

began. Warhol suggested replacing the mural with a portrait of the Fair

official who'd banned the work, Robert Moses, but that idea was rejected

as well. So Warhol began silk-screening the images and exhibiting them

as individual works, and neither the mug shots nor the issues they raise

have been easy to conceal.

|

"At one point we had a few of the images from 'Most Wanted' hanging in our portrait gallery," reflects Tom Sokolowski, The Andy Warhol Museum's director and the curator of the show. "They were on the same wall as all those celebrities and art dealers, but they didn't look out of place at all." It's hard to say which group—the assassins or the art dealers—should be more disconcerted by its likeness to the other. (In the exhibit, the question is playfully taken up by Deborah Kass, whose reworking of the "Most Wanted" series replaces the mug shots with the likenesses of museum curators and other art professionals—a gesture sure to be appreciated by disgruntled artists everywhere.)

In fact, many of Warhol's later paintings of rock stars and society dames would have the same flattened-out quality, the same absence of feeling exhibited in the "Most Wanted" series. Neither the mug shots nor Warhol's celebrity portraits make any pretense at revealing the subject's soul, or indeed anything other than the most superficial characteristics. Warhol's work and life reflected a basic truth of celebrity: The more public an individual becomes, the more that person is obscured by the image created around him or her. Warhol's portraits were as superficial as our knowledge of the superstars depicted in them.

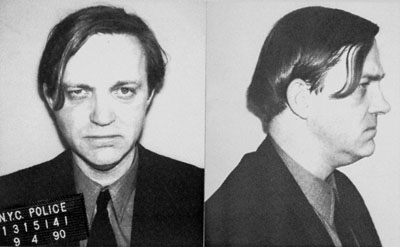

And perhaps what's disturbing about most of those pictured in "Most Wanted" is not how vicious or demonic their subjects look, but how ordinary. The subjects gaze at the camera as blankly as if they were posing for a driver's license photo, while one looks in vain for some stigma of their crimes—if only to mark them as different from ourselves.

This curious emptiness becomes more obvious looking at the photographs exhibited by artist Arne Svenson. Through a series of lucky accidents, Svenson literally unearthed an entire archive of mug shots from a small town on the American frontier—images preserved on antiquated glass negatives. Though the subjects are accused of crimes ranging from "petit larceny" to rape and murder, their faces mostly share a lack of intensity. Comfortably removed by time and distance from the menace they once posed, it's easy to reflect on the absence of malice in their portraits, though as Sokolowski says, "You'd think the most demonic people would have the most intense faces."

Artist Nancy Burson, who specializes in using computers to distort or combine photographic images, has half seriously experimented with that notion. Ostensibly to create a portrait of pure malevolence, she used a computer to combine the facial features of some of the world's most hated dictators. The results, ironically, were vague, uncertain composites that seem portraits not of ruthlessness but of indecision. In this exhibit—as on the cover of this issue—Burson is represented by computer-morphed images combining the facial characteristics of men and women. The result: instead of graphically demonstrating the differences between the sexes, she shows how easily those differences may be blurred, how little the geography of a face can tell us even about the physiology of the body it belongs to.

Sokolowski allows that the exhibition's title is itself somewhat two-faced. "On the one hand, it communicates the notion that this is aggressive, in-your-face art that's politically engaged," he says. But —as is so often true wherever Warhol is concerned—there is an underlying, undermining irony at work. "Much of what we think we're seeing in these photographs is not in your face. It's in the way society sees you."

"It's very important to look at images and see where the real diverges from the artificial. We say a picture is worth a thousand words, but so much of a picture—and the way it is framed—is contrived. Not long ago if you saw someone strung out on heroin, you thought they were just loathsome junkies. Now we have Kate Moss and heroin chic." It's not that criminals have a "certain look" about them, in other words; it's that in some situations, having a certain look can be a crime.

At the least, such beliefs lead us to assume the beautiful people Warhol consorted with were better than they really are. And at worst, such assumptions underlie racism and even genocide. The exhibit reminds us of how high the stakes can get with The Killing Fields, a collection of photographs recovered from the Tuol Sleng Prison in Phnom Penh, where some 14,000 Cambodians were executed by the Khmer Rouge in less than four years. The photographs were taken shortly before the unwitting subjects were to be executed; often, they'd been blindfolded and held captive in subhuman conditions until moments before. Yet most of these subjects stare blankly at the camera, either unaware of or resigned to their imminent fate. If words cannot describe what dictator Pol Pot visited upon his people, if silence is the only expression of that horror, then these are the mute faces speaking that silence.

"The image is not what you're seeing," muses Sokolowski. "It's the frame around it, and what is written there."

In the end, the real subject of all these portraits is ourselves. The blank stare with which the notorious fugitives in "Most Wanted" look out at the world mirrored the empty gaze with which Warhol viewed the images he was creating at roughly the same time in his "Car Crash" series and his silk-screens of an empty electric chair. What makes those unsettling images of death so dismaying is Warhol's cool detachment from them, the terrible silence pervading the death chamber, the voyeuristic appeal that lures us to look at the gruesome wreckage of "Car Crash." And that voyeurism helps explain our fascination with fugitives, or even a madman like the murderous Harry Thaw. In the end, his jadedness is not that much different from the culture that can't tear itself away from him — or any of the other notorious criminals who came after. If we can barely discern a difference between the facial expressions of marauders and their victims, perhaps it is because we see some of ourselves in each.

Chris Potter is the managing editor of Pittsburgh City Paper.

Sources

1. Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. Harvest/HBJ Books, 1975.

2. Chris Riley and Douglas Niven, The Killing Fields. Twin Palms Publishers,

1996.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |