Marthe was an older woman when Bonnard started painting this, but he made her look young. She was obsessively clean—perhaps a hypochondriac—and spent a lot of time in the tub. She died before this painting was completed, and Bonnard himself died a year after finishing it. Because Bonnard was old here and very near the end of his career, one might expect some sort of faltering of touch. But the subject is so important to him that, instead, one sees an infusion of his own longing, and thus a sureness of effect. It's a Proustian painting, of course. She was dead: it's a "remembrance of things past."

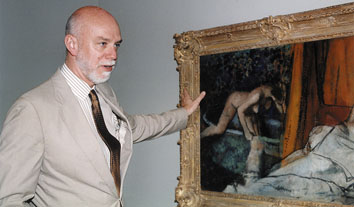

Because of the way it's rendered, The Bath is a very dry picture, with

a superimposition of linear order on top of the colors. An evocative painting,

it is darkly monumental as well. Degas has an incomparable ability to compose.

I like the way he disperses the subject, either by placing it to the edge

of the canvas, or by otherwise obscuring it. In this case, he uses a curtain.

Not seeing her face, I think, makes it more intriguing.

In Wet Orange there is organization of planes. Farmers like rectangular or square fields because that's the way surveyors depict fields—rather than conforming to topography. Mitchell has recreated that sense of organization in paint, with lots of colors representing different shapes on top of the landscape. And her willingness to show us process is very interesting. There are places where she paints "wet-on-wet," and where her instinct is to paint in a grand, gestural manner.

This is a great work, in part because of its size. Like the Monet Waterlilies, it is a panorama. You're enveloped by it, and you feel you are experiencing landscape. It's optically quite rich, and demands attention. It needn't be thought of as having any particular meaning, but the title "Wet Orange" undoubtedly refers to the condition of paint, and you can imagine it as a reference to the water-soaked fields, or to the natural light on the land after a rainstorm. In this painting Mitchell demonstrates kinship with Monet.

One of Hopper's great strengths, it could be argued, is that his subject is light. This celebratory picture seems to me to be either daybreak or late in the day at his hallowed Cape Cod.

Another reason this is such an important painting in the series is that it's a full treatment of the body. We see the body almost fully, and de Kooning gives you a big range of coloration—with slashing brush strokes on both sides. The Woman series was motivated by an advertisement for a cigarette that was cut out of a popular magazine of the era, showing a woman with a full-lipped mouth. I don't know which cigarette ad this was, but it mentioned the "T-zone" around the mouth.

The other great value Woman VI has here is that at that moment the museum was not pre-disposed to abstraction. The museum didn't buy this picture; it was a gift of the great local collector G. David Thompson. This painting bolstered the collection at a crucial moment, and it's truly one of the museum's icons. We show it in a corridor axis, which allows you to compare the realism of female representation from the late 18th-century [George Romney's The Honorable Mrs. Trevor, 1779–80] with this abstraction of the late 20th-century.

Yellow Bath is made out of rubber and polystyrene. Here we are looking at the impression of a very ordinary, everyday object with a function—a cast-iron bathtub. Whiteread configures sculpture through negative spaces, and we're encouraged to see this impression of a tub as an abstraction.

I see now that by picking Bonnard's Nude in a Bathtub and also Degas' The Bath, and Rachel Whiteread's sculpture Untitled (Yellow Bath), I've created a recurring motif of bathing.

I might be showing my evangelical Protestant roots, accidentally. There

is baptism and washing away of sins in some of these pictures. I always

think of art as a kind of salvation, even if there's no afterlife. I think

a lot of artists, and people who like to look at pictures, see art, and

making art, as a way of surviving. As viewers we're lower on the artistic

food chain—we think looking at pictures is in itself a kind of momentary

salvation.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |