Pearlstein was born in Pittsburgh in 1924, attended Taylor Allderdice High School, and was drafted in the spring of 1943 after one year at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University). By then, however, he was already something of a serious artist, winning awards from Scholastic magazine, and having the prize-winning paintings featured in Life. After completing basic infantry training in Florida, he was assigned to a unit producing charts and diagrams on weapons assembly, and spent eight or nine months learning the practical aspects of layout, drafting, perspective and silkscreening.

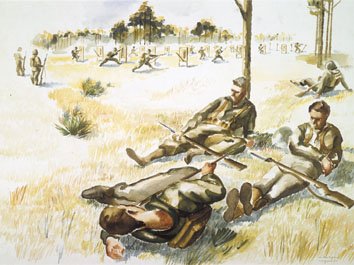

In his spare time, Pearlstein began a series of pen and ink drawings

and watercolors based on what he saw around him, shipping everything home

to his parents throughout his war years. He was, he says in an unpublished

memoir, “tolerated with humor” by the other soldiers.

At the time, Pearlstein thought of himself as an illustrator, and the

drawings have a documentary quality to them that conveys the mood of boot

camp, shipboard life, and the small Italian towns that Pearlstein visited

when he was eventually sent overseas.

These early works, and the paintings that won the awards from Scholastic,

are what Pearlstein refers to as his “genre phase.” In the close attention

to composition, the blocking out of figures, the obvious studied quality

as a figure appears from different angles, we can see the roots of his

later work.

The pictures he sent home caught the eye of his platoon leader and mail censor, who arranged for Pearlstein to be sent to the Headquarters Company in Rome to produce signs and training aids, rather than into combat. The war ended soon after that, just before Pearlstein’s 20th birthday.

In many ways, the war provided an unmatched educational opportunity for Pearlstein. Apart from the art and design techniques he learned at his various postings, he was able to take advantage of cultural opportunities unavailable in Pittsburgh in the 1940s—weekly operas in Rome, and regular visits to Venice, Milan, Genoa and Switzerland. Posted near Florence at one point, Pearlstein took advantage of the bi-weekly trips for mail and laundry: “I spent all the time I could visiting churches and museums to study the art. . . . Even in the courtyard where our truck was parked, the Ghibertti bronze doors of the baptistery were leaning uncovered against a wall.”

Because he lacked combat points, he was one of the last soldiers to

be shipped home, and he used his time well, studying the Masaccio frescoes

in the deserted Church of the Carmine in Florence and climbing up the sandbags

for a close look at Da Vinci’s Last Supper in Milan.

He finally returned home in 1946, completed college, and worked as

an assistant to Robert Lepper before setting off for New York in 1949.

He returned to Italy as a Fulbright scholar in 1958, during which time

he refined his realist style.

The drawings and watercolors from his war years, however, stayed in a drawer for most of the last five decades.

“My son became very interested in World War II at one point, so I put them in a presentation book so you could look at them without destroying them,” Pearlstein says. “They’ve been remarkably well preserved. The ink didn’t fade at all, and it is just ordinary military writing paper and fountain pen ink.”

Though Pearlstein is well-known in Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museum of Art’s

holdings of his work remain meager. Recently, the artist has begun discussions

with Richard Armstrong, Henry J. Heinz II director of the museum, about

adding to its collection of works by Pearlstein. “When the museum held

the traveling retrospective exhibition in 1983, I offered them a gift,”

Pearlstein explains. John R. Lane, then director, chose a painting of Pearlstein’s

parents and a watercolor.

Armstrong now notes, “As a native of our city and a product of its

educational system, Philip Pearlstein is also one of the great artists

of our time. For all these reasons, the museum hopes someday to be able

to represent his work throughout its evolution.”

-Ellen S. Wilson is a contributing editor of Carnegie Magazine.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |