American Indians

Consult on Alcoa Hall

American Indians

Consult on Alcoa Hall American Indians

Consult on Alcoa Hall

American Indians

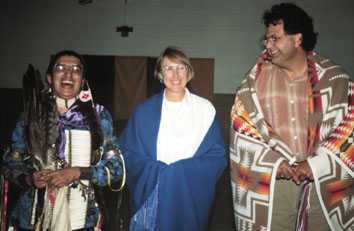

Consult on Alcoa HallAmerican Indians from around the United States have helped the museum staff shape the new Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians. In Pittsburgh, four members of the Three Rivers American Indian Center helped design the area showing contemporary urban life. One of the consultants is Iroquois Pam Soeder.

"It’s important to represent the contributions of urban Indians in different areas," says Soeder, who grew up in Pittsburgh. She scoffs at how Indians are portrayed in the media and in schools, an image that she says leaves Indians stuck in a "time warp." Therefore she was anxious to help portray contemporary Indians properly in Alcoa Hall.

A professor of elementary education at Slippery Rock University, Soeder was especially involved with two sections of the hall dealing with education: a typical college dormitory room of a current-day Indian student; and a photographic retelling of the Carlisle School episode, when early in this century Indian children were forcibly taken from their homes and sent to a school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, to learn "white" ways.

"We want people to understand how it was to be taken from home and forced into other ways," Soeder says of the Carlisle display, "and to stress how things have changed. Today, students willingly go to school to learn more and then go back and help their families and their communities." Typical of modern Indian college students, she says, is the dorm room decorated with traditional tribal items brought from home.

"At Carlisle they were forced to leave it all behind," she says of native items and traditions. "Now the students bring it with them to college because they’re proud of who they are."

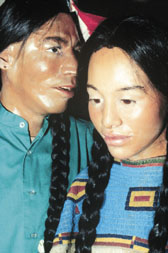

Four members of the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota had their faces cast for the Lakota courting scene. Three of them are relatives of exhibit consultant Nellie Star Boy Menard. The four-hour casting project took place in Menard’s kitchen.

"This was really an event," says Marsha Bol, Alcoa Hall project director. "The whole family watched the process, and a lot of teasing went on as the models had their faces covered with plaster." Several of the Hopi figures bear the likenesses of students from the University of Arizona at Tucson. The little girl in the procession was sculpted free-hand by exhibit designer Pat Martin, based on photographs and measurements of the face of a little Hopi girl in Tucson.

Fred Deer, a

Mohawk Iroquois who was born in Brooklyn and raised in Pittsburgh, had

his face cast for the ironworker that appears in the hall. Volunteering

for the project meant a great deal to Deer, who is part of the long tradition

of Iroquois ironworkers. He worked on buildings in New York, Massachusetts

and Vermont in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Fred Deer, a

Mohawk Iroquois who was born in Brooklyn and raised in Pittsburgh, had

his face cast for the ironworker that appears in the hall. Volunteering

for the project meant a great deal to Deer, who is part of the long tradition

of Iroquois ironworkers. He worked on buildings in New York, Massachusetts

and Vermont in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

"Ironwork is part of who I am," Deer says. His hope is that people will see the display and say, "Remember when we saw ironworkers downtown? Maybe they were Indians."

"The museum is making an improvement, an achievement," Deer says of the addition of Alcoa Hall. "Our people have been misquoted and misunderstood, and this is an opportunity to show a little truth behind what we’re really like. We have doctors, lawyers, politicians - people just as smart and as articulate as anyone else."

-Kathryn M. Duda

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |