For centuries, the Tlingit (Klin’ git) people have lived in tandem with the seas, rivers and conifer forests of the southeast Alaskan coast. These waters and trees provided generations of Tlingit with everything they needed for survival in the temperate rain forests of the Pacific Northwest.

Today, grocery and department stores in nearby Juneau and Ketchikan provide most of life’s necessities. But the forests are still treated with reverential respect, for at one time the Tlingit used every part of the trees they felled. Canoes, construction beams and utensils were fashioned from logs; baskets were woven from roots and other plant materials; and ceremonial regalia, diapers and towels were created out of beaten or shreded bark.

Making garments out of tree bark, or baskets out of tree roots, are difficult tasks and no longer necessary. The museum’s Tlingit consultant, Ernestine Hanlon, says, "There are a few women who still make baskets, but they just don’t do it much. It’s hard work. It’s easier to go to [the supermarket] to buy plastic bags." Those who do make baskets, or woodcarvings or other crafts, often do so for ceremonial purposes, or sell them to museums, collectors, or tourists.

Canoe-making is no longer necessary either. Motorboats are more commonly used for fishing and for transportation, and even airplanes regularly transport people to their destinations.

In the 19th century up to 50 Tlingit lived together in large wooden plank houses, whereas today they live in individual homes. For ceremonies they gather in "clan houses" or in the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) Hall.

The ANB was founded to fight for Indians’ civil rights, resulting in passage of a state anti-discrimination law -- the first to be passed in the United States. The ANB also won the return of millions of acres that the federal government had appropriated for the Tongass National Forest. The government went on to mandate the organization of the Sealaska Regional Corporation and several village corporations, conveyed land to these corporations and compensated the Indians for the remaining land claims. Today Sealaska manages thriving natural resources enterprises for Tlingit and other tribal shareholders. It also supports the Sealaska Heritage Foundation, which seeks to preserve the Tlingit culture by collecting objects, recording stories, and holding a biennial cultural festival. Sealaska employs many Tlingit in its logging operations, while others work as fishermen, in fish canneries, or at various jobs in Juneau and Ketchikan.

Fishing continues as a primary activity and occupation of the Tlingit, who are fortunate to have access to one of the world’s richest maritime environments. The waters of the Gulf of Alaska provide them with a plentiful diet from the sea, with staples including halibut and five varieties of salmon. Fishing rights are an issue now for the Tlingit, with complicated state laws spelling out who can and cannot fish without restrictions.

The Tlingit feel a kinship with animals, such as the bear, whose behavior the Tlingit find human-like.

Tlingit poet Andrew P. Johnson captured the relationship in his 1975 poem, "Bears Are Like People, You Can Talk to Them":

When I see bear tracksI would look at itand I could smell it’s very near."My paternal uncles,I’m here in the woods to get foodfor your grandchildren."

The Tlingit identify themselves as members of either the raven or eagle moities. Within each of these two groups are many clans; and within the clans, families. A century ago, clan and family heirlooms were stored out of sight by a house leader. Today, Tlingit people still store their heirlooms -- like special clothing, rattles and hats -- called at.—ow (ut-oo), and bring them out only for ceremonial occasions when they are worn or held by the hosts or their guests. Tlingit consultant Nora Marks Dauenhauer says that when the crest treasures are brought out in ceremonies, the Tlingit people refer to and "even call upon the [ancestral] spirits represented for healing, courage, strength or purpose, and assistance in the removal of grief."

Carnegie anthropologist Marsha Bol, project director of the hall, says

the Tlingit have had experience with white culture for a surprisingly long

time. Russian, Spanish, French, British and American explorers and fur

traders all arrived in their sailing ships in the last quarter of the 18th

century. The Tlingit culture was not greatly affected until the mid-19th

century, however, when white settlers, attracted by the vast natural resources,

came to stay in Alaska. While this influence is evident in the contemporary

Tlingit way of life, Tlingit Isabella Brady maintains, "We’re very clanish

people. We are proud of who we are."

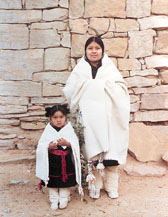

Rainfall is scarce in the dozen Hopi villages perched on the summits of three high mesas in northeast Arizona. But over the centuries, the Hopi people have developed ways of dealing with and even overcoming this arid, harsh environment. Foremost are the specialized agricultural methods that encourage successful crops from their fields and orchards. Three crops predominate -- corn, squash and beans -- and the most important of them is corn.

According to archaeologists, cultivated maize was brought to the American Southwest from Mexico some 4,000 years ago, but Hopi lore holds that corn was a gift from the spirit Maasawu as he greeted people on their emergence into this world. Corn remains vital to these Indians today as a source of nutrition and as an element in traditions and ceremonies.

Hopis have specialized

farming techniques that allow them to produce crops in spite of the arid

climate: planting in areas that catch runoff water after a rain, irrigating

their walled gardens, planting deep to reach trapped subsoil moisture,

planting several seeds in each hole to produce a wind-resistant clump of

plants, and making multiple plantings. After the harvest, corn is spread

on the flat roofs to dry, then is stacked in storage areas and outside

Hopi homes, just as it has been for centuries.

Hopis have specialized

farming techniques that allow them to produce crops in spite of the arid

climate: planting in areas that catch runoff water after a rain, irrigating

their walled gardens, planting deep to reach trapped subsoil moisture,

planting several seeds in each hole to produce a wind-resistant clump of

plants, and making multiple plantings. After the harvest, corn is spread

on the flat roofs to dry, then is stacked in storage areas and outside

Hopi homes, just as it has been for centuries.

Cornmeal is used in more than 30 different dishes regularly served in Hopi homes, and grinding corn is the most important homemaking skill for women. Girls begin grinding at an early age, taking pride in their full bowls overflowing with ground corn. The task is an opportunity for socializing as well. According to Hopi Helen Sekaquaptewa, "If a girlfriend comes to visit, you don’t play around. You grind. She may bring her own corn to grind as you talk." In the past, special grinding stones were used for this task, but most of today’s Hopi women use blenders or flour mills to make cornmeal. The exception is in preparation for ceremonial occasions, when the corn is ground by hand.

Corn also has a major role in all Hopi celebrations, most notably the wedding. In Hopi philosophy the bride is connected with corn, because like corn she is expected to be fruitful and bear children, thus assuring the continuity of life. The bride’s family is responsible for producing vast amounts of cornmeal -- as much as 1,000 pounds -- for gifts and feeding the wedding guests. The corn is ground by all the women in the extended family. The groom’s family is busy during that time as well, for they must furnish cotton for and weave the bride’s wedding garments. Then during the wedding celebration the groom’s family brings to the bride’s family tons of flour, tubs of groceries, sides of mutton and live animals. Preparations for the formal, days-long celebration sometime take so long that the couple, already legally married, have had a child or two by the time the festivities take place.

When a baby is born, corn again plays a role. During a child’s first 19 days, he is cared for by the family’s elder women and is nestled between one or two ears of corn, which are referred to as his "mother." Here are the words of one Hopi grandmother:

"I took you, newly born. I held your warm body against my bared legs. I presented you with your first Mother Corn. I pierced your little ears. For 20 days I cared for you, observing the traditional manner of caring for a newborn childÉ.it was I who named you."

-- Paternal Grandmother of Polingaysi Qoyawayma, 1964.

In a society as agricultural as Hopi, it is only natural that ceremonies pervade their growing season. For six months during this season, Hopis celebrate in hopes of pleasing katsinas, benevolent spirits that can deliver rain for the crops. During the six-month season, initiated men from the tribe impersonate katsinas and make appearances at ceremonies, offering gifts and friendship. Racer katsinas challenge men and boys to foot races, and others perform antics and chastise people for unacceptable behavior. Some visit children at their homes, frightening naughty ones into changing their ways, and making sure they’re learning what is expected of them. Boys must demonstrate that they’re learning to plant, weave and provide for their families, and girls show that they know culinary skills and the uses of herbs and medicines. To prove their progress, children give the katsinas a gift.

"The proof is how you respond to these figures when they come to visit your house," explains Hartman Lomawaima, a Hopi consultant for Alcoa Hall. "The boys will trap mice or rats and give them as a kind of tribute to the giants. The girls will make miniature tamales to give to them." While Hopis request that no photographs of katsinas be displayed, their likenesses are visible in katsina dolls that are given to young girls.

In July, the day after the Hopi observance of summer solstice, the katsinas

return to their home in the San Francisco mountains, and the Hopis are

left to harvest their crops, knowing that they did their best to please

the spirits that can let them starve or flourish.

Over the course of the 19th century, however, several factors caused the numbers to plummet from millions to zero. Introduction of the railroads was a significant factor: the lines interrupted the buffalo’s normal migratory routes, and their construction crews required large amounts of fresh meat for food. Sport hunters descended, often shooting the animals from the trains. Rail transport also satisfied an increased demand for buffalo hide and meat in the eastern United States. Other factors in the buffalo’s demise included three dry periods over 40 years, significant Native consumption, and increased competition for grasslands from cattle and horses.

The loss of the buffalo was devastating to the Lakota people, but a small public herd was protected in Yellowstone National Park, and from it the numbers slowly began to increase. Today, Plains people manage growing herds, and most tribes seek to preserve and increase herds through membership in the Inter-Tribal Bison Cooperative.

Many Lakota people are currently involved in a grassroots effort to protect buffalo from wandering out of Yellowstone and into Montana, where they can, by law, be killed. According to Marsha Bol, hundreds of these buffalo have been killed in Montana in recent years, for fear that they carried brucellosis, a disease that can kill cattle. One group of volunteers, called Buffalo Nations (buffalo@wildrockies.org), physically surrounds straying buffalo, protecting them from Department of Livestock agents who are in the area around Yellowstone to capture buffalo that cross park boundaries.

In a letter to President Bill Clinton, Buffalo Nations’ leader, Rosalie Little Thunder, implores his help in saving the buffalo:

"In the late 1800’s, 60 million or more buffalo were mindlessly slaughtered, in a very deliberate, calculated move to starve and conquer the native peopleÉ.It is happening all over againÉ.You will find the same brutal violence that this country was built uponÉ.You have signed an executive order, directing your agencies and departments to consult with tribes on matters that affect them. The buffalo are of historic, cultural, and religious significance and we have not been consulted in a meaningful mannerÉ.You must honor Government-to-Government Relations and tribal consultation in determining the fate of the sacred buffalo, your national symbol."

Another animal important to Plains people, the horse, was traditionally linked to hunting and war. Recognizing the animal’s contribution, Plains people covered their horses in magnificent decorations, according to its value and the status of its owner. Today, hunting is not a necessity but a sport, and warriors on horseback are only seen in the movies. But the horse remains relevant to the Lakota lifestyle. Women parade on horseback during the annual Crow Fair, and children practice horsemanship and compete in rodeos.

Many Plains men and women have found a way to keep alive the warrior tradition -- through active service in the U.S. military. Lakota people served in all of the 20th century wars and conflicts, and they take great pride in serving their country. Veterans have honored roles in family and tribal life, and they often wear visible signs of their participation in the service -- commemorative belt buckles, T-shirts, caps and jackets. Photographs of men and women in uniform are prominently displayed in many Lakota homes.

According to Joe Medicine Crow of the Crow nation, "World War II was

responsible for revitalizing the culture. Men could resume their warrior

status." A veteran of World War II, Medicine Crow unknowingly fulfilled

all the requirements for becoming a chief while he was at war. He touched

an enemy, took his weapon, captured his horse (actually a band of horses

belonging to SS officers) and led a successful war party.

|

The Lakota tradition of patriotism is tempered with political activism. Beginning in the 19th century, Plains Indian leaders delivered some memorable speeches during treaty negotiations with the U.S. government, drawing on a heritage of remarkable oratory. In 1968, Lakota men founded the American Indian Movement (AIM), the militant Indian rights group. To commemorate the 1890 massacre of Chief Big Foot and his band, and to protest ongoing Indian oppression by the U.S. government, AIM organized an occupation of Wounded Knee Creek in 1973, which resulted in a 71-day stand-off with federal law enforcement officials.

Despite daunting social and economic problems, today’s Lakota people

maintain a rich ceremonial and community life, knowledge and use of their

native language, and an expressive artistic heritage.

|

The next time you find yourself in a Pittsburgh landmark like the U.S. Steel Building, the Civic Arena, or the Fort Pitt Bridge, consider the men who built it -- many of them were Indians from the northeastern United States. Iroquois ironworkers, especially those from the Mohawk nation, are well-known for their fearless skill in erecting skyscrapers and steel bridges in cities all over the country -- particularly in the northeast, where the profession was born.

In 1886, construction

of the Canadian Pacific Railway Bridge across the St. Lawrence River required

permission to build the southern abutment on reservation land. Leaders

from the Kahnawake Reservation agreed, as long as the construction company

would hire men from the reservation. It was a perfect match, with the Iroquois

showing particular talent for ironwork. One company official commented,

"Putting riveting tools in the Mohawks’ hands was like putting ham with

eggs." (Editors, "High Steel Mowhawks" in Realm of the Iroquois, Alexandria,

VA, Time-Life Books, 1993, p. 163) Once trained, the ironworkers traveled

in groups from city to city to work on successive projects, returning home

on weekends.

In 1886, construction

of the Canadian Pacific Railway Bridge across the St. Lawrence River required

permission to build the southern abutment on reservation land. Leaders

from the Kahnawake Reservation agreed, as long as the construction company

would hire men from the reservation. It was a perfect match, with the Iroquois

showing particular talent for ironwork. One company official commented,

"Putting riveting tools in the Mohawks’ hands was like putting ham with

eggs." (Editors, "High Steel Mowhawks" in Realm of the Iroquois, Alexandria,

VA, Time-Life Books, 1993, p. 163) Once trained, the ironworkers traveled

in groups from city to city to work on successive projects, returning home

on weekends.

Now more than a century old, the profession has been in many Iroquois families for generations. These ironworkers take great pride in their work, and many see it as a contemporary version of the lifestyles their forefathers led. Traditionally, Iroquois men traveled a great deal, following opportunities for hunting, fishing and trading. Today’s Iroquois men see themselves as carrying on the tradition of traveling to find ways to support their families.

Iroquois women have always operated the households and clans and held roles of great responsibility and power. Even today, clan mothers select the male council members, or chiefs, and have veto power over the men’s decisions.

Women’s work traditionally included farming, and their crops were corn, beans and squash -- the Three Sisters who, it was believed, sustained the Iroquois both physicially and spiritually. Corn was raised in several varieties, and it provided them with more than just nourishment. Women braided the husks for rope and twine, and coiled them into containers and mats. Shredded husks provided kindling and filling for pillows and mattresses. The cobs became bottle stoppers, scrubbing brushes and fuel for smoking meat. Silks were the hair for cornhusk dolls -- items still made and sold by Iroquois women.

Women’s creativity and business acumen helped save the tribe in the early 19th century when the Iroquois found themselves needing alternative sources of income. Diminishing land and a decrease in the number of game and fur-bearing animals meant fewer opportunities for earning a living, so the women took their artwork to nearby resorts and tourist attractions. There, vacationers delighted in purchasing beaded items of many types, so that by mid-century the arts had become a major economic activity for the Iroquois and their neighboring Northeastern tribes. These items, much the same as they were in the Victorian era, are still sold at the New York State Fair.

Today the Iroquois live mainly in New York and Canada, on several reservations. For nearly 200 years they had also occupied land in Pennsylvania, but the federal government broke an agreement in the early 1960s and the Iroquois lost their property.

Known for two centuries as Cornplanter’s Grant, the tract of land along the Allegheny River was given to the renowned Seneca war chief and leader, Cornplanter, by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1791. The land was a reward for helping to keep the Seneca nation neutral during the Indian Wars in Ohio. The deal was solidified with the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794, the oldest treaty in the United States, which was signed by George Washington’s representative and Cornplanter. The treaty guaranteed that the United States would never take the land away from the Seneca nation.

Cornplanter opened up the land to some 400 Seneca, which represented about a quarter of their total population. Tucked between the river and the mountains, the Seneca were protected and continued to live in their traditional ways for generations.

Then in the 1960s the United States confiscated most of the land by the right of eminent domain, for purposes of building a dam to control the flooding of the Allegheny River. Cornplanter’s descendants and the Allegany Senecas fought to stop the construction, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision. In 1965 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed Kinzua Dam, which flooded out all of the habitable land in the grant, plus another 10,000 acres of the Seneca’s Allegany Reservation in New York.

The federal government continues to honor part of the Canandaigua Treaty: Every year, fabric is given to the Iroquois as annuities in payment for their land. Seneca G. Peter Jemison says, "We know that that treaty is still being recognized because every year in the fall we are sent treaty cloth. And that treaty cloth has gone from a calico "to a cheap muslin." Our clan mothers say, "We don’t care if it gets down to the size of a postage stamp; the principle is that you are still giving us that cloth because you recognize that this treaty is still in place.’"

Kathryn M. Duda is associate editor of Carnegie Magazine.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |